James Seay’s newest book, Open Field, Understory, contains new poems and selections from his earlier books. The collection, arranged from latest to first, evokes a journey back toward beginnings. It is an exploration of Seay’s craft.

“It’s probably something that’s puzzled or intrigued me,” he says, “so that I want to make sense of it. I’m not ever going to discover truth with a capital `T.’ But I do hope that I can discover a truth about that image or experience.”

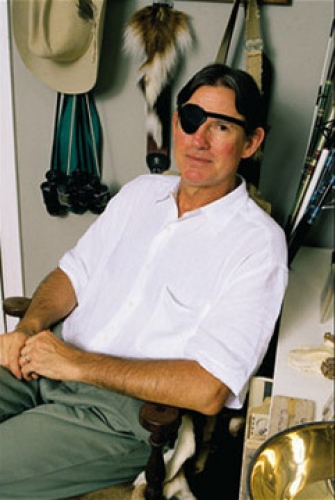

James Seay is a professor of English and an acclaimed writer whose poetry and nonfiction has appeared in magazines and journals as diverse as Esquire and Antaeus. But little in his background suggested that he would become an academic. He’s from a family who lived “close to the land” in Mississippi. His father’s side milled trees and moved earth; his mother’s farmed and blacksmithed. He was the first of his family in a long time to go to college, though his father could recite poetry from his own school days. And both sides of his family had a strong narrative tradition. They liked to talk, tell stories, and make jokes.

It wasn’t until Seay dropped out of college for a few years that he began to write and read with a purpose. While working in Memphis, he spent most of his free time in the library, reading all the poetry he could find and taking night courses at a local university. He knew then that he wanted to return to college and experiment with creative writing.

When he did get back to school he tried both fiction and poetry but gravitated toward poetry. “It generated a particular kind of energy in my psyche, and I felt more confident doing it.” That’s when he started gathering material for his first collection of poems.

Nearly thirty years later, he’s published four more books, headed the creative writing program at UNC-CH, and gained widespread recognition for his work, most recently an American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Literature and a Bowman and Gordon Gray Professorship for excellence in undergraduate teaching.

His poetry has developed a subtlety Vereen Bell, long-time friend and Vanderbilt University English professor, calls “rich in humor.” Seay says he doesn’t take himself as seriously now as he did in his earlier work. He describes the voice in his first book as “too rhetorical, too insistent on its drama.” In his later works he says, “I’ve tried to level with the reader more. I want my poems to have a voice that seems fairly natural, fairly close to conversation, but with the essential difference that it’s not just talk, it’s poetry. It’s compressed, it has a rhythm, a sense of music.”

If one of Seay’s poems is not controlled by rhyme and meter, it will often end up syllabic-its line length determined by its syllable number. As well, he likes to employ off-rhymes, inexact rhymes such as “hook” and “joke,” that faintly echo each other and remind us that poetry is a craft, and there are certain conventions to follow. He says he’s skeptical of writing that sounds too close to “back-fence talk,” a phrase he borrows from friend and Mississippi writer Barry Hannah.

It is clear that Seay draws on personal experiences for his poems-many have dedications attached. “The poems are a measure of the depth of my feelings about friends and family,” he says. “They mark our shared experiences.” As you read through his books you can trace the growth of his children and of his relationships with friends and self. But, as he emphasizes, his poetry also has fictional elements.

“When a poem is in first person singular, the `I,’ the `we,’ it can have the feel of autobiography. But remember, a poet has no final obligation to his personal history in a poem. A poem is different from nonfiction-you can take bits and pieces of your personal history and transfer it to a page, but you are always free to depart from the lines of history. That’s when the life of the imagination is at work.”

Seay explains the merging of fictional and real experience through one of his poems, “Time Open-Faced Yet Secret Before Us.” In it, Seay describes a river swim with friends in which an alligator makes a cameo appearance in their yearly group portrait. This is where reality and fiction divide, for in the real event, although there were indeed alligators in the river, an alligator never surfaced. But Seay says, “I wasn’t trying to retrace history, I was trying to honor the truth of the feelings I wanted to reveal-feelings of male bonding and bogus notions of bravery.”

Seay often shapes his poetry with narrative. But he says, “I’d like to write a purely lyric poem-just a moment lived in time that doesn’t have any narrative or abstraction.” He’s not sure if this is possible, for as he says, poems are like cameras-they act as mediators between viewer and view.

And mediation has its drawbacks. It’s difficult for Seay to remove himself from his work because so much of his craft is tuned to turning his observations and experiences into poetry. “Often what I’m doing in my mind is relating forward, anticipating a poem, and that’s not always good because it tends to get in the way of the immediate experience.” That’s one reason he’s interested in working on lyric poems, to loosen the sense of mediation, the view through the camera lens.

Seay’s newest book, Open Field, Understory, contains twenty new poems and selections from his earlier books. The collection, arranged from latest to first, evokes a journey back toward beginnings. It is an exploration of Seay’s craft. The last poems of the series emphasize this focus. Written nearly thirty years ago, “Kelly Dug a Hole” reflects a writer’s hope that a well-crafted thing can survive what Seay calls “the ruin that Time is always promoting.”

The walls and floors

Are spider-cracked in places

From some slight shifting,

But the building stands

And if any part will hold

When things begin

to slide and fall

That part will be

Where Kelly dug his hole.

Shoring against time, digging into the earth, shelter and survival: this early poem and the collection’s epilogue share similar themes. The epilogue, “Deep in Dordogne,” is one of Seay’s most recent works. It explores the beginnings not only of Seay’s poetry, but of all poetry. Seay wrote the poem after a trip to France. While driving to visit Lascaux, he missed his turn because of snow-covered signs, and ended up in the village of les Eyzies de Tayac, a town with its own set of caves. As Seay tells it, “It was mid-winter, and I was literally the only person at the site. On impulse, and against the posted rules, I climbed up the side of a bluff and took shelter in one of the caves. And then I realized the obvious-my caves aren’t back in the States; these are my caves. Taking the long view, this is where I came from. And so I sat there on the floor awhile and looked out at the view.

Julia Bryan was formerly a staff writer for Endeavors.