Chuck Stone doesn’t fit the stereotype of a salty old newsman. There’s no cigar, the clothes are pressed. He wears a bow tie and cologne. And you won’t find him in a crowded newsroom. Stone, the Walter Spearman Professor in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication, surrounds himself with crumbling volumes and time-softened paperbacks. Mostly, they’re essays on freedom-of speech, education, religion, people. Stone surrounds himself, that is, with ammunition. His mission, he says, is to free people.

Go back with him a few years.

Between 1987 and 1991, while he served as a senior editor and columnist for the Philadelphia Daily News, 75 people “surrendered” to Stone rather than go straight to the police. He was the middleman between the suspects and the police, who Stone says had a reputation for brutality. Five of those occasions were hostage crises.

One of these was at Pennsylvania’s Graterford Prison, November first and second, 1981. Four murder convicts had tried to escape, then had taken six hostages and holed up in the kitchen. They stayed there for four days.

The ringleader of the group was Jo-Jo Bowen, who had gone to jail for murdering a policeman. In prison he had stabbed to death a warden and a deputy warden. When Bowen threatened to execute the six hostages, officials called Stone in to negotiate. He was the only one Bowen would agree to talk to. “I damn near had a nervous breakdown,” Stone says. “I spent two days negotiating and they released the hostages after the second day. So then when people got in trouble and there were hostages… they said, ‘call Chuck Stone to get us out of this.’”

It’s not the résumé you’d expect from a journalist and educator. But for Stone, it follows naturally from his belief that oppression in any form should be fought tooth and nail.

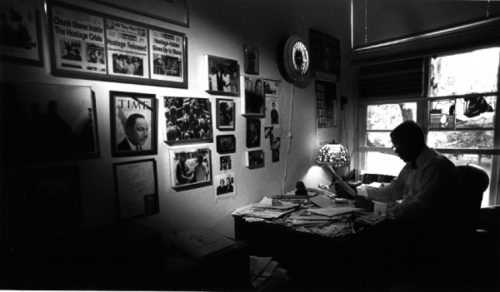

The office he inhabits on the second floor of Howell Hall is his den. Sunlight streams through a stained-glass ornament in his window. Visitors sit in rocking chairs or a puffy, green-and-white-striped sofa. The room is also study, library, living room, and kitchen, with a microwave oven beside his desk. It comes in handy during the long sieges of meetings with students and colleagues. Preparing to teach his classes in censorship and magazine writing. Working on his study of test scores for students in communities where blacks make higher salaries than whites. Supervising his national survey of journalism students’ attitudes on the media, ethics, and national leaders. Writing his weekly, nationally syndicated column.

He’s also got four books in progress-an anthology of Walter Spearman’s works, an anthology of historic African American sermons, a study of selected decisions in First Amendment cases as canonical literature, and a media-law book for Delaware.

Stone’s conversation, like his office, is a mosaic. He quotes politicians, philosophers, and the scriptures.

“‘Is this not the path that I have chosen,’” Stone repeats from Isaiah, “’ to… undo the heavy burdens, to let the oppressed go free, and that ye break every yoke?’

“That’s my mission,” he says. “To break every yoke.” Stone has broken yokes from Philadelphia to Egypt, to India and back. In Philadelphia, he was known for writing columns that stung politicians-black or white. And though he preaches black political solidarity in the voting booth, nobody gets his endorsement on the basis of color alone. While editing the small black weekly New York Age, Stone pulled down a little flak himself-for hiring a white reporter and a white woman columnist when no white paper in town was hiring black writers. He used to call himself “ombudsman for the brothers.” Now he calls himself “ombudsman for humanity.”

Following service in the Air Force and degrees in political science, economics, and sociology, he spent a year with CARE distributing food packages in Egypt, Gaza, and India. At New York Age, he struck up strong friendships with U.S. Rep. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., and Malcolm X.

Stone moved to Washington, D.C.’s Washington Afro-American as editor and White House correspondent in 1960, where Newsweek magazine labeled him “the angry man of the Negro press.” He strengthened that reputation the following year by getting fired from the editor-in-chief position at the Chicago Daily Defender, refusing to soften his attacks on Mayor Richard Daley.

After Stone’s dismissal, Powell hired him as his chief administrative aide. Stone became one of the principal players in the black power movement, organizing the National Black Power Conferences held in Washington, D.C., Newark, and Philadelphia in 1966, 1967, and 1968. The second conference started on July 17, 1967, three days after the end of the Newark race riots, which had gripped the city for five terrible days. Stone says he was pleased with the turnout-over 1,000 attended-but, like Washington’s more recent Million Man March, the results were hard to quantify. “It’s a moment in history,” he says. “You can’t point to any concrete achievements that resulted from [it].”

It’s the nature of Stone’s work: well-defined steps, intangible results.

Stone has spent much of his adult life shuttling back and forth among newsrooms, broadcast studios, and classrooms at Syracuse, Bryn Mawr, Harvard, and Delaware. The subjects he teaches vary, like his columns, from politics to journalism to social work.

The wake of the O.J. Simpson acquittal brought a number of invitations to speak on radio and television talk shows. The day after the verdict, he spent the afternoon at the Swain Hall studios of WUNC-FM, a guest on National Public Radio’s live call-in show, “Talk of the Nation”. A day later his guest column ran in USA Today. A strong advocate of feminism, Stone finds a special meaning in the letters of Abigail Adams, whom he calls “the world’s first feminist.”

His mother’s picture is at the center of an arrangement of snapshots and portraits that adorn his office walls. The picture is an enlarged, black-and-white snapshot of a slim African American woman with a just-bloomed smile.

“I’d really like to live in a society where women are fully equal,” he says. “I think women are a humanizing force in our society -just better human beings.” In an ideal world, he says, the proportion of women and minorities in Congress would match their percentage in the U.S. population.

Perhaps foreseeing the continuation of racial strife, Stone observed in 1968, as did others like him, that American culture is not a melting pot after all. In Black Political Power in America, one of the three books he published between 1968 and 1970, Stone likened American culture to an emulsion bowl, where particles co-exist but never become a unified substance.

This uneasy suspension causes problems for some students. Stone says he occasionally is approached by an African American student who feels racial tension in the classroom or in social settings at the University. Stone encourages such students to stand firm.

“I tell them, ‘Lookit, your grandparents fought this. They had less than you did; they had a wall of segregation. For you to cop out now is to betray that legacy. You’ve gotta nurture that legacy. You’ve gotta build on it.”

Stone lingers over Humboldt’s preface to John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty. “Everything in this passage points to opening up society so people can enjoy it to their richest diversity.” Stone relishes the phrase “richest diversity,” repeating it, as he does sometimes, to enjoy it: its roll over the tongue, the nuances of the sound.

He has also taken on as his personal mission the first part of that statement: “opening up society” is a constant refrain, another way he describes the work he does. But it’s his life’s work.

“We are all prisoners, to some extent, of our ethnicity,” Stone says adamantly. And freeing the prisoners is something he’s known for.

Marissa Melton was formerly a staff writer for Endeavors.