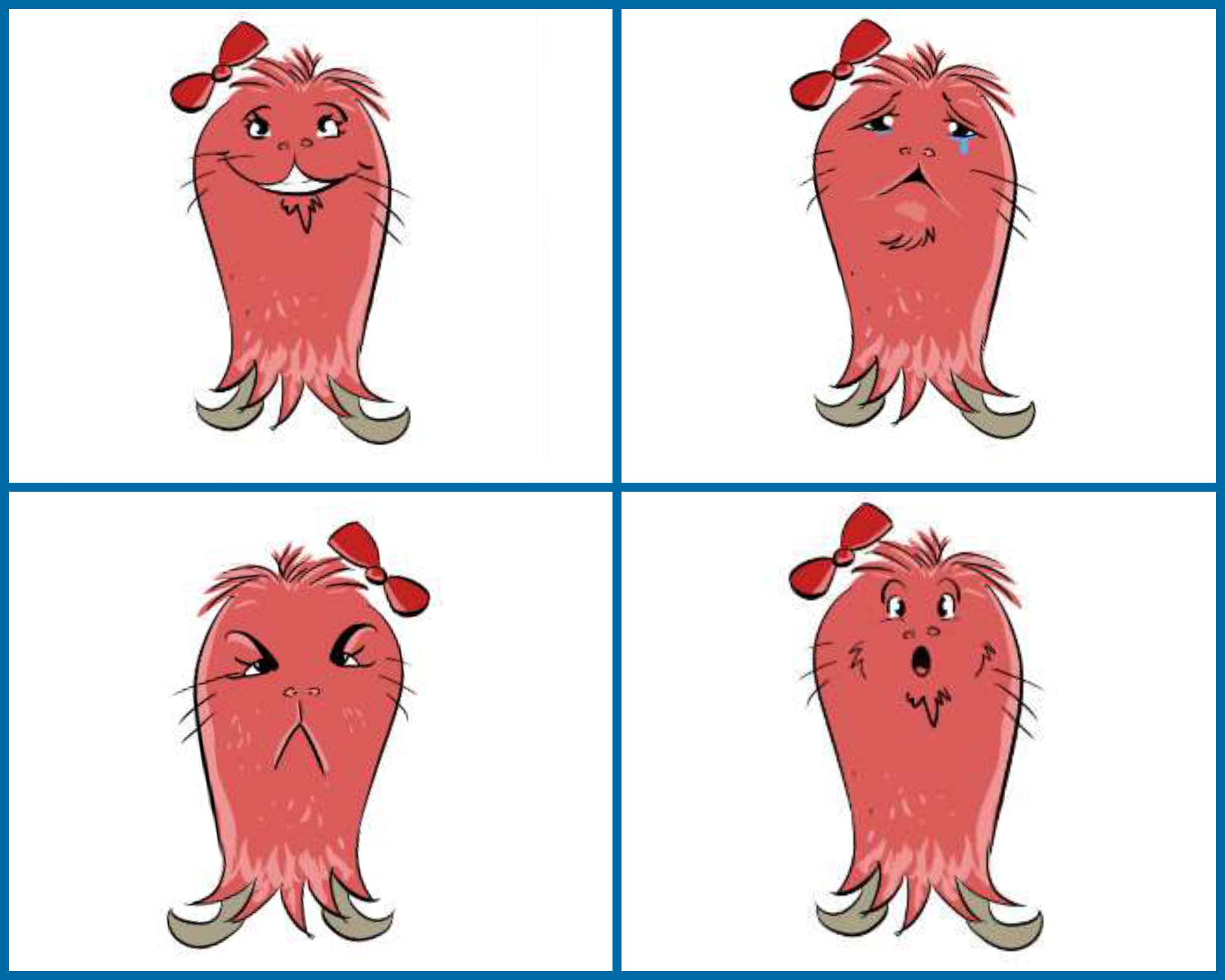

Palooza is a pink alien, similar in resemblance to “Itt” from “The Addams Family.” Because she comes from another planet, she speaks a totally different language than us. She uses words like “daxy” and “torpy” to describe how she feels.

During the summer of 2016, children at the Museum of Life and Science in Durham found themselves mesmerized by Palooza and her friends — Chrysanthemum, Chromia, Wazu, and Xylobean.

These aliens are animations used by UNC psychology and neuroscience professor Kristen Lindquist and linguistics professor Misha Becker in a research study on emotion and language. The two want to know the role language plays in how 3- to 5-year-old children understand and express emotions.

“Infants can experience broad emotional states — positivity and negativity,” Lindquist explains. “But it’s not really until they’re toddlers that they begin developing emotion concepts and are actually able to use them in spoken language.” As children grow and develop, how does emotion impact language, and vice versa? Thanks to a Fostering Interdisciplinary Research Explorations (FIRE) grant, the two can learn more about that connection.

From aliens to hand puppets

Why aliens? “I was a little worried that if we showed kids pictures of humans showing different facial expressions, and we tried to teach them a new word for this emotion, they might be resistant to accepting the new word,” Becker explains. Children practice mutual exclusivity — if they already have a label for something, they’re reluctant to give a new label to that same thing.

“You show a kid a cup and a turkey baster,” Becker says. “If they don’t know what the turkey baster is, and you say, ‘Give me the zorp,’ they’ll hand you the turkey baster because they already have the word ‘cup’ in their vocabulary.” Using aliens for the study also appealed to the fun and colorful nature of children. “They capture your attention much more than pictures of posed human faces,” Lindquist adds.

Lindquist and Becker developed two different studies to run with their 3- to 5-year-old participants. The study using the aliens involved an animated video that told a short story followed by questions. They manipulated syntactical structure — grammar principles that govern the structure of sentences — using words like “is,” “feels,” and “feels about,” but also looked at the impact of context by adding more detail to the story. One of the videos showed Xylobean taking a walk on a beautiful, sunny day. Then, he finds a penny on the ground. That made Xylobean feel “gorpy.” Children then had to identify the meaning of this new word.

Illustration by Shawn Daley

“The context information was created in a way to elicit an emotion in a way that wasn’t overly obvious or too subtle,” Holly Shablack, the graduate student lead on the project, says. “We wanted to provide kids with a sweet spot in-between to see at what age they can pick up syntactical structure and at what age context plays a role.” After watching a video, the children were given a picture selection test with three images of Xylobean. In one, he’s exhibiting an emotion like happiness, in another he’s experiencing a physical state like hot or cold, and in the last he’s performing an action such as running or falling.

The second study utilized videos of hand puppets and manipulated only syntactical structure. “There is a lot of evidence that, by this age, children have a good understanding of how verb meanings relate to overall structure of a sentence,” Becker says. “So when you give them a made-up verb in a sentence, they can make a good guess about what that verb means.” Becker’s previous work shows that these biases about the relationship between sentence structure and verb meaning works for adjectives, too, but this is the first time she’s studied how adjectives refer, specifically, to emotions.

The scenarios among puppets were simple:

“I know an alien who is stroopy,” the pig says.

“Really, you know an alien who is stroopy?” the lamb asks.

“Yeah, I know an alien who is stroopy,” the pig replies.

“Oh, you know an alien who is stroopy,” the lamb says.

From the kids’ responses to both studies, Lindquist and Becker discovered that without providing more context than just the syntactic structure, only the 5-year-olds were able to figure out that the alien was experiencing an emotion. When context was provided and the linguistic structure suggested an emotion, though, both the 4- and 5-year-olds connected the new words to emotions. “As kids are becoming more adept at using language, they’re able to distinguish and draw from the context in a much more fine-grained way,” Lindquist explains.

Tackling the whole spectrum

In the future, Lindquist and Becker hope to explore bilingualism and how this may affect the way a child forms emotion concepts. “Languages can differ from each other in exactly which emotion concepts they label and what kinds of distinctions among the different emotion concepts they make in terms of vocabulary,” Becker says.

Some hypotheses about bilingual adults suggest that having different systems of emotions makes such people more emotionally complex, according to Lindquist. “You can see nuances because you know that in this language you parse things one way and in another language you parse things in a different way,” she says. “But it’s hard to know how that would developmentally play out.”

The two have also looked into studying language as it applies to autism. Some people with autism have difficulties interpreting emotion through expressions, and others experience a language deficiency. “But there have been very few studies about those things in connection with each other,” Becker says. “How do children with autism develop their emotional vocabulary?”

“This could have applications for the type of training that’s now being imported into lots of different schools for helping kids become more emotionally intelligent,” Lindquist says. “In order to do that, we have to know how kids learn about these concepts.”