How do you take words off a page and make them into a performance worth watching?

The job is hard enough when the text in question is straight fiction, furnished with characters and a plot. But to take an indefinable book such as Let Us Now Praise Famous Men and try to make it live and breathe on stage requires bravery and, yes, a bit of brass. Derek Goldman has both.

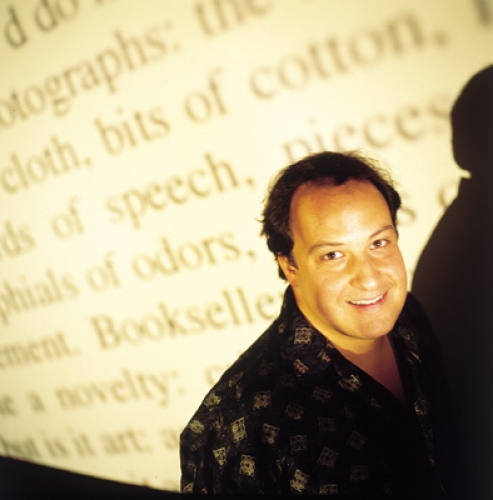

“The books that I am always attracted to,” he says, “are ones that first of all move me but that also feel like they demand the particular creation of a new style to make them come alive.”

Goldman, assistant professor of performance studies, dramatizes words. Not just a book’s story or character but the words themselves and his reaction to them. “Almost anything I read,” he says, “the first time through, I’m already thinking, what would this be like read aloud? And, how would you stage this? What are the parts that I’m reading fast to get to?” He trusts his instincts and chooses what moves him.

Goldman began thinking this way in high school, when he and other students worked with the Brookline (Massachusetts) Educational Theater Company to create plays about issues such as drug abuse and freedom of speech. “We would work in groups with adults from the community, reading articles and adapting them into skits or scenes,” Goldman says. Excited by that and other theater work, Goldman majored in performance studies at Northwestern University. Now, more than ten years after those first plays, Goldman teaches his students to find drama in everyday encounters with words, whether those words are in a novel, a menu, or instructions on a parking ticket. “I try to make them aware that they’re always responding to text, that all texts have a potential to be made into a performance,” he says.

Goldman needed all his experience when he took on James Agee and Walker Evans’ Let Us Now Praise Famous Men this spring. With Agee’s text and Evans’ stark black-and-white photos, the book is the product of a month spent with three tenant-farming families in 1936 rural Alabama. Anything but a straightforward account, it does contain some scenes and dialogue but has an equal amount of essaylike rants, passages that verge on poetry, exhaustive descriptions of clothing worn and food eaten, even a page from a third grader’s geography textbook.

Goldman adapted Let Us Now Praise Famous Men as the last show of the 2000-2001 season for StreetSigns Center for Literature and Performance, the professional theater company that he founded in Chicago and brought with him to Chapel Hill in 1999. He directed a cast that included UNC-CH students, some local professional actors, and communication studies professor Paul Ferguson.

One thing that intrigues Goldman about Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is how it “strives to represent other people in a way that will transcend the limits of what a book is usually able to do,” he says. Agee talks “torturedly and obsessively” about the idea that it’s impossible to fully do justice to these people’s lives. To that end, Goldman didn’t assign actors to particular parts. When characters do appear, they are never portrayed by the same actor twice.

“There’s a kind of fluidity of identity that the ensemble ends up taking on,” Goldman says. “In general, what we’re not trying to do is what an actor typically does, which is represent the character of the Alabama tenant farmer in a way that’s meant to suggest ‘this is exactly what they were really like, this was the way they gestured, this was their accent, and I’m taking you inside their character, persona, or experience.’ Agee’s whole point was that it’s impossible to do this.”

G

oldman also chose to have some pieces of the text spoken in unison by the ensemble, and other pieces spoken by one actor. That’s partly because he sees some passages as being about universal truths, while others relate to very specific, private moments. “The text in many ways is like a piece of music,” he says. “It felt to me like harmonizing between the individual consciousness and the collective consciousness.”

For instance, in “Near a Church,” Agee tells of accidentally frightening an African American couple when he runs after them to ask for information. Agee tries to reassure them but soon realizes that, as a white man, he automatically poses a threat to them and that there’s no way he can put them at ease. Goldman has one actor speaking most of Agee’s narration but also has all the white members of the cast advancing with him toward the two African American actors portraying the couple. “In a way, Agee’s trapped in his own whiteness,” Goldman says. “So there’s something about having all those whites in the background.”

Such an approach doesn’t make for straightforward rehearsals. Going into the five-week-rehearsal period, Goldman knows pretty much how he wants the scenes to look and sound. But he uses rehearsals to fit the different parts and movements to the personalities and strengths of his cast. Two weeks before opening night, he and the actors are still occasionally experimenting with who will say a line here or cross the stage there.

But Goldman is as characteristically calm as he was in the first throes of planning and casting. “The style and the rules have to be made particularly between us as an ensemble,” he says. “This is the part that I really love.”

Throwing the book to the floor

It’s been said that many a reader has thrown Let Us Now Praise Famous Men to the floor, “maddened by its resistance to ever settling into a familiar story or a coherent, sequential narrative,” as Goldman puts it. He was hoping his audiences wouldn’t feel the same way. “I hope that people don’t give up on it because they’re confused by the form,” he says. “There are some scenes that are moving in familiar ways. And then there are parts that are definitely more philosophical, intellectual. So you hope that you’re giving them enough candy to keep them, that those more familiar scenes make the audience want to work harder in the scenes that demand that.”

And the cast has to keep working hard too. Goldman and stage manager Sarah Woods (a senior) worked with the actors relentlessly on not paraphrasing one line of the lengthy script. “A lot of Agee’s language is so flowery and beautiful that if it’s paraphrased it’s easy for it to get very general in tone, and then it can get kind of precious,” Goldman says. And that’s when the audience may tune out. “Agee’s whole drive was to be as exact as possible about what’s really true about these people. In order for the performers to share that with the audience, they have to know precisely what it is they’re getting at. They have to guide the audiences through those sentences a little bit.”

A little confusion is okay

Some people loved the play. And some were confused. “A few of my students said, ‘What was that?’” Goldman laughs. But that’s okay with him. “With a text like this, if you’re being faithful to it, you have to allow for the fact that you’re gonna have to make some new conventions, and it’s not gonna be a totally familiar experience for the audience. Because, as Agee keeps saying, it’s an experiment.”

The press gave the performance good reviews, though, which helps. And several people came back more than once, always a good sign. Goldman says, “That is part of what is exciting to me about this kind of project—that it is demanding of the audience.”

Streetsigns produced Let Us Now Praise Famous Men in association with the Department of Communication Studies.