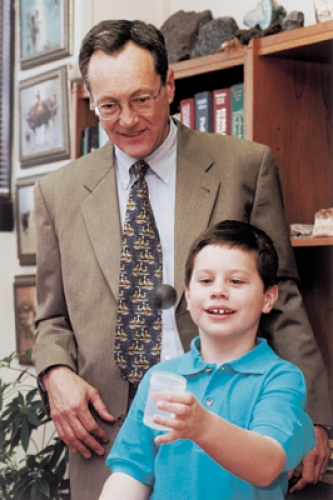

How do you properly introduce someone who’s been called the next Dr. Spock?

Anyone who reads Newsweek, the San Francisco Chronicle, Teacher Magazine, or Southern Living, for instance, has probably read about Mel Levine, professor of pediatrics, and All Kinds of Minds—the institute he founded to help children become more successful learners.

One way would be to start with Levine’s eccentricities. He lives about an hour outside of Chapel Hill on a 30-acre farm he’s named Sanctuary. There, he and his wife, Bambi, raise hundreds of geese, 10 donkeys, a horse and a mule, seven dogs, 40 pheasants, 19 peacocks, and 10 swans.

Or you could start with the origins of Levine’s interest in learning problems: Levine says that he was an awkward child and not very good at sports. During baseball games at camp, he would play right field for both teams and pass the time searching for snakes in the grass and reading biographies. It was here, he says, he figured out that nobody’s good at everything.

Then there’s the moment when Levine found his calling. After earning his medical degree in 1969, Levine enlisted in the U.S. Air Force and was stationed in the Philippines, where he volunteered as the school doctor at Clark Air Force Base. This is where, he says, he realized kids learn in many different ways.

You could also begin with Levine’s philosophy “label the problem, not the child.” Levine believes that the students themselves should understand their differences. “Whether or not they have learning problems, students need to know how their minds work—learn about learning while they are learning,” he says.

Levine, director of the Clinical Center for the Study of Development and Learning, explains that every student is “wired” a little bit differently. Whether Levine’s personally seeing a child or presenting a workshop to teachers, the first thing he does is create a profile of each student’s strengths and weaknesses.

The profiles come from a model consisting of eight neurodevelopmental constructs ranging from memory to higher-order cognition. “The names [for the constructs] are pretty unimaginative,” Levine says, “but we call them constructs to convince ourselves that we constructed them, so that we’re prepared at any point to change them.”

To help teachers identify where a child is having difficulties, Levine and his team of researchers have created observation tools that teachers learn during “Schools Attuned”—a 35-hour professional-development program for elementary and professional school educators. The Teacher’s View is an online tool that has 12 different “windows” with checklists to examine tasks such as “call on the child in class and listen to the way he speaks” or “analyze a writing a sample.” The window for calling on a child in class, for example, includes items such as “never uses a compound or complex sentence,” “is hesitant in speech (you want to jump in and help),” “has trouble finding words,” and “has poor transitions between sentences.”

After the teacher observes the child, she enters the information into the program, which analyzes the information and figures out where the child may be having the most difficulty. The program then provides suggestions to the teacher. For example, “In the four windows you have completed, everything that you’ve checked off that is problematic concerns memory. Here are some recommendations that you may want to think about for that child.”

Another tool helps kids see their trouble areas for themselves. The Concentration Cockpit likens a child’s attention to the cockpit of an airplane with various meters for measuring mental processes. As each meter is explained, the child marks where he thinks his needle is.

The idea behind the tools is to help parents, teachers, and clinicians “demystify” children. “So many children have these terrible fantasies about themselves—that they were born to lose or that they are severely retarded, stupid, brain damaged, or weird,” Levine says. “And the truth is always so much less stigmatizing, so much less horrifying than what they’ve started to think about themselves. We take the mystery out by demystifying them.”

Levine says the tools also represent ways of translating neuroscience into things that kids can get their arms around. “It’s our belief that you can’t really work on something if you don’t know what it is,” he says.

Once teachers and kids figure out where a child’s difficulties are, they can work together to come up with some solutions to bypass those weaknesses. For a kid who has trouble paying attention, a teacher can use a prearranged clue to tell the child to get back on task without humiliating him or her, or allow for frequent breaks during which the child can stretch or walk around before getting back down to business.

For students who have problems with memory—for example, struggling to come up with the right answer when called on in class—Levine suggests having the teacher warn the child the day before. The teacher can say, “Susan, I’m going to call on you tomorrow to tell us about the causes of World War II. Can you get ready for that?” This gives students 24 hours to prepare, and when they answer the question correctly, it will help them gain confidence.

To Levine, the most important tactic is “strengthening strengths.” “Teachers should be able to identify children’s affinities or areas of passion, so that every child can become an expert at something,” Levine says. “Children ought to be able to pick a topic they’re interested in and study it for three of four years, so that they are the school’s leading expert.” By the sixth grade, a student who is interested in mummies, for instance, will have written several reports, completed a couple of art projects, and done a few science projects on the topic. “Every child should have a taste of expertise,” Levine says.

In high school, another way to strengthen strengths is to give students the option of taking their weakest courses pass-fail. In the courses selected for grades, teachers could make students work really hard, so that, in a sense, Levine says, every student would be an honors student in something.

There are many critics who believe Levine’s approach to education is too idealistic, that his ideas aren’t grounded in science. “The critics are correct in a sense,” Levine says. He explains that some of the components of the neurodevelopmental constructs in his model have not been rigorously and scientifically studied.

The question, Levine asks, is what do you do in the meantime? Ignore the problem until science catches up? For example, Levine sees a lot of kids who have problems with time management. He says, “They don’t understand how time works, they do everything at the last minute, they don’t know when they’re running ahead or behind, they are always late, and they drive their parents crazy because they don’t know how to do anything in a staged way.

“But I can’t tell parents, ‘I’m sorry but the National Institutes of Health haven’t had a chance to study time management and what parts of the brain are involved. Can you come back in 20 years?’”

“A lot of what we do at the center is trial and error,” Levine says. “Our first priority is to do everything as scientifically as we possibly can, but, as a clinician, I don’t have the luxury to wait. I have to respond to people’s immediate needs.”

Levine has a wide circle of supporters too—those who are helping him make the waiting process a little easier. One supporter is Charles Schwab, who is cochairman of All Kinds of Minds and recently gave the institute a $10 million challenge grant. In the late 1980s, Schwab’s son was diagnosed with dyslexia. After his son’s diagnosis, Schwab realized that he also had dyslexia; it just wasn’t something that was recognized during his youth.

The Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation also supports Levine and has awarded grants to teachers so they can attend “Schools Attuned.”

“But there are a whole lot of things teachers can do that don’t cost money,” Levine says. “Mainly, it’s understanding more kids better, being more flexible with them in the classroom, and being more understanding about giving them time and space to grow.”

Catherine House was formerly a staff contributor for Endeavors.

Later this winter look for a Public Broadcasting System (PBS) special on Levine’s work.