Karla Rosenberg believed the world was black and white. As a white girl who lived in Central Durham and attended predominately black public schools, she also thought she was a minority.

Riding the bus home in middle school, Rosenberg always recognized the Macon Street stop, not far from her own house, because more students got off there than at any other stop. “I watched every day as my black classmates poured off the bus and onto their lawns after school,” she says.

Five years later, Rosenberg was surprised when she drove down the same street — almost all of the black households had been replaced by Latino households. “It seemed a huge change had occurred right under my nose,” she says.

Mexican tiendas started popping up. Ranchero music played on the street. And in the restaurant where she had worked part time in high school, a lot of the people working in the kitchen were Latino.

“All of these things sparked my curiosity enough that when my mother invited me to begin teaching English classes with her at a local Hispanic community center, I eagerly accepted,” Rosenberg says.

And the Latinos were just as eager to learn English. “All of the classes were packed,” she says. Each class focused on a different issue such as health care or worker’s compensation. For one class, a policeman came and talked about crime in the area. “This is when I realized that crime in the poorer areas was mostly black and Latino. Latinos carried all of their money around with them because they didn’t trust the banks, and this made them easy targets for violence,” Rosenberg says. “It really hit home when a Latino dishwasher I worked with in the restaurant got shot walking home one night.”

Rosenberg began to wonder if there might be some connection between black-Latino hostility and blacks’ perception that Latinos were taking over their jobs and housing. She kept this thought in the back of her mind as she finished high school and started college. When her senior year rolled around, though, she knew her honors thesis was the perfect opportunity to explore the impact of Latino immigration on the native black community.

“Latino immigration in this area is a recent phenomenon, so there’s not a lot of research data out there,” Rosenberg says. Census figures show that between 1990 and 2000, the Latino population in North Carolina quadrupled from fewer than 100,000 to around 400,000.

Rosenberg went door to door for her information. She interviewed about 15 employers, workers, residents, and landlords — both blacks and Latinos. She asked questions about their community and about work — what it was like, whether they enjoyed it, if they thought the wages were fair, how they interacted with people on the job.

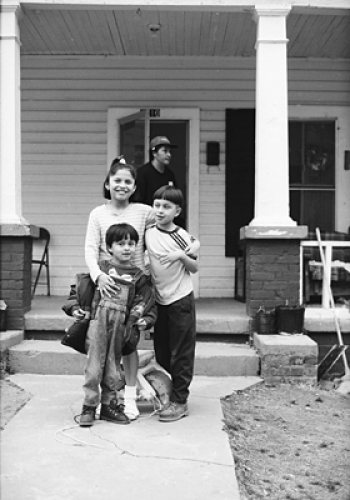

“Everyone was very open,” Rosenberg says. “It wasn’t so scary. I guess I’m pretty nonthreatening.” Petite, with long reddish hair and freckles, Rosenberg says she got more jokes aimed at her than hostility. It helped, too, that she speaks fluent Spanish, something she picked up volunteering at the Hispanic community center and gets to practice regularly with her boyfriend, who is from Mexico.

lot of the Latinos Rosenberg talked with started out in the United States living in New York or Los Angeles, but because the job markets in those areas were already pretty saturated, they migrated to places such as North Carolina where job opportunities are plentiful. She adds that many Latinos now bypass the bigger cities and come directly to North Carolina.

Rosenberg says Latinos tend to find jobs easily because they are typically willing to work for lower wages and are perceived by employers to have a strong work ethic. They also use their friends in the community. “There’s a lot of networking among Latinos,” Rosenberg says. “And employers are going to be more likely to hire a friend of somebody already working for them rather than somebody they don’t know off the street. The same thing works for housing. Latinos will move into a house in the neighborhood, and when the next house opens up, they jump right on it and get it for their friend.”

Most of the black people Rosenberg talked with said they did not necessarily feel that Latinos were taking over their jobs. One man living in a homeless shelter surprised Rosenberg by saying, “There’s no problem finding a job. There are jobs here for everybody who wants them.” Rosenberg says that most blacks are better educated and have higher-level jobs than immigrants. Those without education and high-tech skills, though, often felt themselves at a disadvantage in competition with Latino workers.

“Another thing to think about,” Rosenberg says, “is the economic downturn we’re facing. What’s going to happen when economic opportunity dries up, when the high-tech jobs are gone and African Americans and whites are going to have to seek lower-level jobs? They’re not going to have anywhere to go because the Latinos are already there.”

Rosenberg also points to research done in September and October after 9-11 that shows a disproportionate amount of job loss among African Americans as opposed to whites.

While Rosenberg, or anyone else for that matter, doesn’t have any immediate solutions, she believes that immigration can be healthy for a community. “I think fear is keeping a lot of people from embracing a community that adds richness of life and work. Latinos actually provide a lot of work,” she says. “If you look around at all of the buildings being built, the Latino food and restaurants — it’s incredible. I definitely think they’re benefiting our country economically as well as culturally.”

Catherine House was formerly a staff contributor for Endeavors.

Rosenberg’s thesis advisor was Lars Schoultz, professor of political science.