We all know that symphony concerts are for listening. Dress up in fancy clothes. Don’t talk. Don’t move. Just listen.

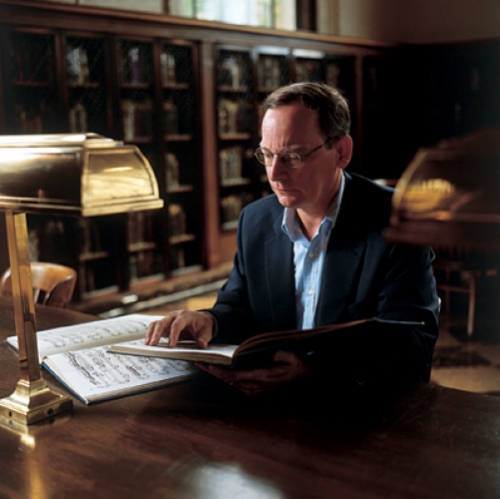

But Beethoven’s contemporaries would be surprised to see that kind of behavior at a concert, explains Evan Bonds, professor of musicology. At the large outdoor music festivals that sprang up throughout Germany in Beethoven’s lifetime, symphonies were as much participatory events as listening experiences. “The more musicians, the better,” Bonds says, leaning forward slightly in his chair and smiling as if to say he might like to participate in a sport like that.

A violist himself, Bonds became interested in the interaction between people and their music through studying the way people received Beethoven’s symphonies during his lifetime. While teaching a course at Boston University, Bonds found many references to the connection between the symphony and politics in the nineteenth century — the time in which Beethoven was composing.

“I wasn’t looking for these things, but I kept running into them,” he says. “I was a little skeptical at first. I thought these were people who were trying to push a particular agenda. But there were so many of them, and after a while I began to realize that this was really part of the way people heard symphonies in the nineteenth century.”

Sitting in his office surrounded by symphonic scores and stacks of history and music books, Bonds explains that a symphony has many distinctive features in the world of music. For one thing, it is played without any single instrument dominating. And symphonies have no words, at least not most of the time. “I think that allowed people to hear it in a very open way. It allowed for a lot of different kinds of interpretations,” Bonds says.

In accounts of music festivals that featured performances of symphonies, people generally didn’t talk about the quality of music making. “They talk about how many people participated. The important thing was the enthusiasm of the players, most of whom were unpaid amateurs. This was something you did as a community,” Bonds says.

One of the reasons behind their enthusiasm is that music festivals were one of the few public gatherings sanctioned by government officials. “Nineteenth-century Germany and Austria were pretty much police states,” he points out. “Germany, moreover, was only just beginning to discover its own cultural and national identity, and symphonies — especially symphonies by Beethoven — were an important means for citizens to generate a sense of shared community.”

Bonds says that Beethoven was “in the right place at the right time.” His music was different and powerful, but it probably would not have had the same impact had it not been created at a time when people were inclined to hear the music in the context of emerging democracy. And he is quick to point out that although Beethoven was the most notable symphonic composer of the time and participated in discussions about politics and society, he was not the only composer in the nineteenth century whose works contributed to discussions of democracy.

The German music festivals, existing at a time of great political change, were not just about playing music. There was a subversive undertone to the events. Bonds says that in Germany at that time, people were not allowed to gather in large groups. “Large gatherings were something that the authorities got very antsy about,” he says. But music festivals were okay because they were just music — at least on the surface.

“Because there were no words, no one could be thrown in jail,” Bonds says. “The music festivals were a way of creating a political alternative.” Each musician was as important as the next, just as in a democracy each person’s vote counts as much as the next. “No voice is more important than the others; they are all essential to the whole,” he says. In other genres of music, such as the concerto, there is a soloist, and the orchestra serves as the background.

The content of the symphonies underscored democracy as well. Take Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. “That actually gives voice to the whole idea of brotherhood and joy,” Bonds says. “The symphony is about joy. And that’s the same type of joy our Declaration of Independence talks about — life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It’s this idea of freedom, of self-fulfillment.”

While there is no direct evidence that Beethoven was a part of this subversive subculture, there are plenty of indicators that he was. Bonds gives an example from one of the conversation books people used to communicate with Beethoven after he became deaf. “Someone visiting the composer once wrote something along the lines of ‘if only the authorities knew what you were saying in your symphonies.’ It’s kind of tantalizing because we don’t know what Beethoven’s answer was, but the idea was out there.”

In some ways, the same kind of connection between nationalism and music happened with people coming together after September 11. Bonds mentions groups of people spontaneously singing “God Bless America.” “If they’re really sincere about it, it can be quite moving — everybody in Yankee Stadium singing one song, that’s very powerful,” Bonds says. “That’s the same kind of force that the symphonies had in the nineteenth century. They were really a way of building community.”

Mary Alice Scott was formerly a staff writer for Endeavors.

Bonds received a fellowship from the American Academy of Berlin to do research for his book, The Music of Ideas: The Culture of the Symphony in the Age of Beethoven. He will be in residence there in fall 2002.