They had been sitting on the floor for close to an hour in absolute silence, and Norris Brock Johnson was starting to get fidgety. Finally the priest gestured through the open wall in front of them, pointing past the immense stones in the pond to another outcrop that, for the past seven hundred years, has formed a waterless waterfall. “The only reason I have been drawn to the garden,” the priest confided, “is that I love the garden very much. There are gardens in many other temples, as you know, but I love this garden in this temple.”

Johnson knew exactly he meant.

It was 1985 when Johnson first set foot in the Temple of the Heavenly Dragon (or Tenryū-ji, pronounced ten-ree-yoo-jee). He was an anthropologist with a Fulbright, teaching classes in Tokyo on American culture and traveling around the country on the weekends. He was visiting Arashiyama — a mountain town west of Kyoto that’s famous for its cherry trees — when he saw the temple in front of him and the memories hit: his grandmother at the kitchen sink singing I come to the garden alone, while the dew is still on the roses…, his mother’s plot of flowers and vegetables, and the little Japanese black lacquer box she used to let him play with.

“I don’t know if I can explain it exactly,” he says. Put simply, he was immediately in love with the place.

Johnson has studied many of Japan’s Zen Buddhist temple gardens over the past twenty years, but Tenryū-ji was the first. “Living in that temple changed my life,” he says.

Tenryū-ji is the ivy league of Buddhist monasteries, and people from all over the world apply to go there to study Zen and zazen (a form of practicing Zen that calls for long periods of cross-legged sitting). The temple was first built more than six hundred years ago. It’s an incredibly peaceful place, Johnson says, and you’d never guess that over the centuries it’s been blown up, laid siege to, and battled over by emperors and shoguns and warrior monks. It’s been burned to the ground no fewer than eight times — the last was in 1864. But the original landscape garden has survived, and now it’s one of the oldest in Japan.

Johnson went back to Tenryū-ji again and again, lingering in the public areas long after the other visitors had left. He questioned caretakers and anyone else he could about the grounds, but no one seemed to know much about its history. Johnson wasn’t even sure why he was doing it, but finally, a little nervous and holding out his business card, he approached a receptionist and asked to speak with someone who knew about the garden.

Eventually the local expert appeared — a senior priest who was the only one of some twenty resident priests who had any knowledge about the grounds’ history. He looked pleasantly at Johnson for a long moment, then asked, “Why are you here?”

Johnson didn’t expect that. He frantically weighed his possible answers — to study your culture, to research the temple, to find something — and in the end discarded them. “I don’t know, exactly,” he said.

The priest nodded. “Come back again. Make an appointment to speak with me.”

Johnson did go back. “For the first six months, I visited constantly,” he says. “I kept staying late. They had to boot me out at closing time.” In the end, his persistence paid off. The priest extended a rare invitation: “You really should stay weekends,” he said, “so the garden can begin to speak to your heart.”

It took some time for Johnson to get used to sleeping on the floor in unheated rooms, to waking up at 4:00 a.m., to communal bathing with the monks, and to using partition-less, unisex squat toilets. He wasn’t allowed to speak with the other monks, who were in strict training. “It’s the quietest place I’ve ever been,” Johnson says.

While he was there, he had drawn-out conversations with the priest about the garden. Eventually, he was allowed to walk alone through the restricted parts of the grounds that the public never sees. He took photographs, made sketches, and pored over every inch of the pond garden.

“We don’t usually think of inanimate things as beings,” Johnson says, “but some other cultures do. Beings have a quality of metabolism, of growth and change. If you look at a garden over time, you’ll see that, like a person, it changes.” So on his evening walks, he started to ask the garden questions: Where are you from? Why are you here? What was your childhood like?

To get answers, he spent years studying Japanese history and language, Buddhism, Zen, architecture, mineralogy, and geology. But those questions were Johnson’s first steps in writing Tenryū-ji: Life and Spirit of a Kyōtō Garden. The story of the temple grounds and their often brutal history includes what little is known about the garden’s builders, intimate descriptions of the temple’s private interior, and translated bits of his conversations with the priest. And he says it’s been decades in the making.

Tenryū-ji began in 1339 when Emperor Komyo gave Buddhists permission to build a temple on the site of an old villa. A priest named Musō Kokushi became the temple’s first abbot, and named it Tenryū-ji, or “Precious Zen Temple of the Celestial Dragon.” People said a dragon slept in the pond there, so the name seemed like a logical choice. (In Japanese culture dragons are protective, divine beings that often hibernate in lakes and rivers. They’re associated with fecundity, growth, and well-being, Johnson says.)

Johnson and the priest continued their discussions. The priest told Johnson the Buddhist names and meanings of things in the garden, and he was curious to hear about Johnson’s life as a university professor. Their exchanges had a glacial pace — they took years. One of the things Johnson learned from the priest was that the vegetation of the garden isn’t nearly as significant as its stones.

Stones have a special place in Japanese culture — they even show up in the national anthem. Stories about the earliest gardens in Japan include stones that were inhabited by Shintō deities.

Shortly after one of his chats with the priest, Johnson reread the Epic of Gilgamesh — a poem from 3000 BC — and found that it includes what may be the first-ever written description of a garden. The cuneiform poem was carved on clay tablets in ancient Sumer (present-day Iraq). On Tablet XII, King Gilgamesh, the often-despicable antihero of the story, wandered into the mountains in search of immortality. He was stopped by man-dragon creatures who, “seeing his great intent and will,” allowed him to pass through the gates to the sun god’s garden. That garden, Johnson says, was made entirely of stones — there were bushes made of pearls and agate, and trees bore carnelian fruit, lapis lazuli leaves, and hematite thorns.

Suddenly Johnson had to re-examine the very idea of what a garden is. Now that virtually all human societies practice agriculture, he says, we tend to think of gardens as horticultural places to grow plants for food. But before agriculture, humans’ survival depended upon stone tools, so it makes sense that the first idea of a fruitful plot of land would consist of stones.

Johnson took a year after that to study stones, and then went back to Tenryū-ji to continue his conversations.

“Maybe it’s because I grew up on a farm helping my father, who was a carpenter,” Johnson says, “but I really wanted to know more about the people who actually built the garden.” Today, the priests at Tenryū-ji don’t maintain the grounds. If a stone tumbles over, no one can touch it until licensed state workers come and set it right. And when Johnson began to look into who the original workers were, he says, the details were shadowy.

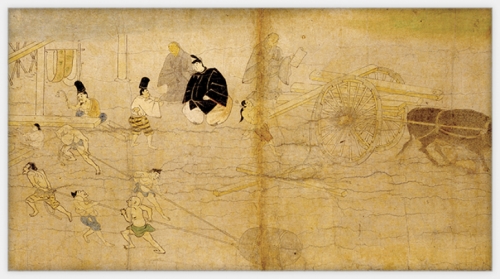

No one book on the subject exists, and it took a lot of digging before he’d pieced together enough information to understand why: the mysterious Riverbank Gardeners, as the builders were called, were barely human (or so people said) and no one at the time bothered to record much of anything about them. Their caste was so low that individuals didn’t have their own names — they were simply called by the name of the collective group: kawaramono sensui.

The kawaramono were relegated to living on the muddy, disease-ridden banks of the Kamo and Katsura rivers. Some Japanese paintings from the time depict them as hunched over, dark, and leering; other people in the scenes, especially the nobility, are relatively bright and tall. Rather than pay taxes, the kawaramono did manual labor, slaughtered horses and cows for leather armor, and worked as corpse-handlers for the samurai, who needed bodies on which to test their swords. The kawaramono also cleared away the human debris after battles or disasters. But their intimate knowledge of gardening, stones, and the earth was famous, and people believed that in making gardens, the shaman-like gardeners actually brought the realm of the spirits into the realm of human beings. Johnson found that the kawaramono had built many of the gardens and temple landscapes in Japan, including the gardens at Tenryū-ji.

After the workers spent five years hauling boulders and moving earth, the garden was complete. The kawaramono were never allowed on the grounds again; they were too unclean for such a sacred space.

But how could the Buddhists — known as studious and spiritually enlightened — justify supporting such a system of labor? “For many Buddhists at the time, it was incongruous,” Johnson says. Most Buddhists considered even the act of moving a stone lowly and spiritually polluting. But a few high-ranking Buddhists (namely Musō) were known as “stone-setting priests,” and they sacrificed their reputations by working side-by-side with the kawaramono. “Musō insisted that all work in the secular world revealed Buddha,” Johnson says. This was Musō’s personal practice of Buddhism.

The last chapter of Tenryū-ji answers some of Johnson’s most pressing questions. Why are we drawn to gardens in the first place? Why do some peoples, such as the Japanese, crave garden retreats so intensely that they invent miniature versions (think bonsai trees and rock gardens in trays) to enjoy in the middle of the city? And why do Buddhist temples have gardens at all?

One reason is historical, Johnson says. The earliest Buddhist temples in Japan mimicked those in India, which generally had gardens with cistern-like ponds for water and utility within the compound. Not to mention that Siddhartha (or the Buddha) is said to have been born in a garden. The final reason, though, is pedagogical: the priests at Tenryū-ji point to the garden over and over again to illustrate lessons about Buddha and to train monks to look past the surface of the world’s people and things.

Johnson found this out when, one day, he and the priest sat together in silence, looking out at the stones in the water. Their reflections made the pond look bottomless, the priest pointed out, although it’s only three or four feet deep at any point.

“It is not good enough if the pond garden gives an impression of flatness,” the priest said. “It is important to give an impression of hidden meaning.”

For Johnson, that moment, and the notion of the garden as a mirror, has lasted.

“While Gilgamesh was in the Garden of the Sun, perhaps he saw his reflection in the carnelian leaves and what he saw was the slayer of his friend Enkidu and the destroyer of the mythic cedar forests,” Johnson says. “At Tenryū-ji, I liked what I saw when the garden looked back at me.”

Norris Brock Johnson is a professor of anthropology in the College of Arts and Sciences. His book, Tenryū-ji: Life and Spirit of a Kyōtō Garden, will be published by Stone Bridge Press in early 2009. He received funding for his research from Dumbarton Oaks, the Institute for the Arts and Humanities, the University Research Council, the Japan Center, and from UNC-Chapel Hill. He held teaching positions in Japan at Waseda University and the University of Tokyo, Komaba.