Imagine that a man wants to win the lottery, so he randomly picks five numbers and buys a lottery ticket. He wins. Did he do it intentionally? Most people say no; it was just luck.

Now imagine that a man wants to kill everyone in town, so he randomly picks five numbers and causes a nuclear meltdown. Everyone dies. Did he do it intentionally? Most say yes.

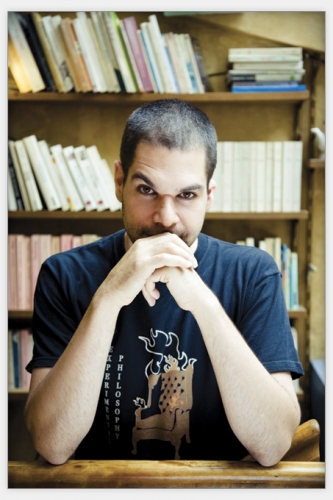

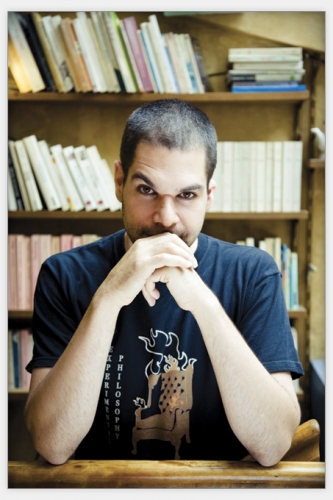

That second scenario was luck, too, but the immoral act of killing people trumps luck, Joshua Knobe says. Knobe is one of the godfathers of experimental philosophy, a new movement at UNC and other schools that seeks to answer philosophical questions by asking actual people.

Knobe has asked hundreds of people about intentional action. And no matter the question, it seems that morality wreaks havoc with people’s perceptions of intention — even though most philosophers had thought for years that morality played no role in determining whether an act was intentional.

“You’d think that people would first try to figure out what’s going on in someone’s mind,” Knobe says, “and based on that people make a moral judgment, such as whether the person is to blame.”

The Knobe Effect, as it’s now known, occurs when we first figure out if something is morally right, wrong, or neutral, and then determine if a person did it intentionally.

Consider this:

A manager tells his CEO that the firm’s new plan will earn a lot of money and help the environment. The CEO says, “I don’t care about the environment, I just want to make a profit.” The company goes ahead with the plan. It makes a profit and helps the environment. Did the CEO intentionally help the environment? An overwhelming majority of people say no.

Now consider the opposite: a manager tells his CEO that the new plan will hurt the environment. The CEO says, “I don’t care about the environment, I just want to make a profit.” The company goes ahead with the plan and makes its money, but the environment is harmed. This time, the vast majority of people say the CEO intentionally harmed the environment. “In this case, we seem to decide that it’s morally wrong to harm the environment, and for that reason we end up concluding that the CEO intentionally harmed the environment,” Knobe says.

Other philosophers have asked different groups — psychopaths, four-year-old kids, people from other countries, people with autism — the same or similar questions. The evidence is clear. Bad behavior — and even morally good behavior — seems to influence how we decide whether or not an action was done intentionally. And Knobe, too, is sometimes under the influence.

“The way I develop these experiments,” he says, “is to look inside myself and just think about what I’d say, and then I think, ‘Wait, I’d say all this weird stuff!’ Then I ask other people and they say the same things.”

But why would Knobe take to the streets to ask a bunch of ordinary people what they think? Isn’t philosophy the classic armchair endeavor? Not for Knobe and a group of mostly young philosophers who have embraced experimental philosophy — x-phi for short — a new movement that’s getting mixed reactions within the larger discipline. Some philosophers think x-phi crosses the line into pop psychology, though many veteran thinkers don’t dismiss it outright.

Carolina philosopher Tom Hill, an expert on moral theory, says, “I think it can be valuable as long as good and sophisticated philosophers, such as Josh, are very careful about what conclusions they draw from their data. That’s the really controversial part — how and in what ways the empirical information is relevant.”

Geoffrey Sayre-McCord, who chairs Carolina’s philosophy department, agrees that experimental philosophers need to be careful about how they draw conclusions, but he also thinks x-philes are on to something good. He says that philosophers have always been dedicated to analyzing, articulating, and evaluating concepts such as free will and intentional action in the hope of finding definite answers. “But most philosophers do this depending solely on their own understanding of the concepts,” Sayre-McCord says. “A key feature of experimental philosophy is how it works to uncover the nature of the concepts.”

In the CEO experiment, Knobe found that 90 percent of people said that the CEO intentionally harmed the environment, but just 20 percent said the CEO intentionally helped the environment.

“Now, the temptation is to say, ‘Well, this just shows that people are no good with the concepts,’” Sayre-McCord says. “But there’s a real bit of hubris in that dismissal. If you get robust results consistently, then there’s good reason to think, for instance, that our concept of intentional behavior has a moral element. I just don’t believe that philosophers have a lock on the concepts. So it’s relevant to try to figure them out.”

Although some other philosophers say x-phi turns traditional methods of critical thinking into the Gallup Poll, Knobe argues that x-phi actually is traditional philosophy.

“For almost all of history, philosophers were concerned about what human beings were really like,” Knobe says. “They wanted to know about human emotions, how human passion and reason interact, whether morality is innate or something we learn, and so forth.”

But in the twentieth century, many thinkers embraced analytic philosophy, which Knobe says can read something like this:

Action (a) can be intentional if and only if the following six conditions are met: There exists some objective (o), such that the agent is seeking (o), and there exists —

“It’s a very technical, quasi-mathematical discipline,” he says. “X-philes see themselves as sort of returning philosophy to the way it was traditionally — interested in a broader range of people.”

Knobe didn’t invent man-on-the-street Q&As, but his fingerprints are all over x-phi’s genesis.

As a Stanford undergraduate in 1993, Knobe teamed up with a psychology grad student to conduct field experiments about the mind-set people need to have for a particular action to be considered intentional.

Photo by Vinciane Verguethen; ©2008 Endeavors.

Click to read photo caption. Photo by Vinciane Verguethen; ©2008 Endeavors.

“We didn’t see this as philosophy,” he says. “We published our work in a psychology journal.”

Knobe had no intention of becoming a philosopher. He feared becoming an academic; he wanted to work with people. So he worked several jobs after college — teaching English in Mexico, working at a homeless shelter, helping people find affordable housing — but on weekends and after work he couldn’t help but write about philosophy, a hobby he had indulged since high school.

In 2000 Knobe finally took the plunge and starting doing doctoral work at Princeton. He noticed that young philosophers at other universities were conducting interesting experiments. Then he read an article written by a Florida State University professor who deduced from Knobe’s psychology paper that morality had nothing to do with how humans view intentional action. “When I read his article, I thought, ‘Wait, that has got to be wrong,’” Knobe says. “So I started doing experiments to prove that this thing I wrote was wrong.”

That’s when he concocted the CEO experiment. Since then, he has come up with many more questions to uncover what humans are thinking when morality and intentionality collide. And a lot of young philosophers have embraced his way of doing philosophy.

Discussions of x-phi have heated up on blogs. Some thinkers question the method’s validity. Others love it. And some x-philes seem to revel in the controversy. Knobe isn’t really one of them, but his wife, musician Alina Simone, wrote an x-phi anthem that philosophy department staffer Jennie Dickson turned into a YouTube video in which the only image is an armchair on fire.

X-phi has now infiltrated many philosophy departments, including Carolina’s. Doctoral student Felipe De Brigard has used experimental philosophy to challenge a long-standing theory about what humans value.

For centuries, many philosophers thought that everything humans do could be boiled down to the pursuit of pleasure. In the 1970s philosopher Robert Nozick devised a thought experiment to see if that was true. He thought that if given a choice between living in a virtual-reality machine (in which life would seem wonderful), and living a real life (no matter how terrible), people would choose the real life. This, Nozick thought, meant that people don’t value pleasure above all else.

De Brigard, though, wasn’t sure Nozick’s idea told the whole story. He decided to ask people what they thought, adding a twist to Nozick’s experiment.

Imagine you’re already plugged into that virtual-reality machine and living a wonderful fake life, and then there’s some technical glitch that makes you aware of the situation. So the scientist in charge says you can choose to stay in the machine or return to your real life.

De Brigard wanted to know what people would do if they found out that their real lives would be terrible, or wonderful, or a complete mystery. When told that their real lives would be terrible, 90 percent of people said they wanted to resume their wonderful virtual lives. When De Brigard gave people the other two options, 60 percent of the people still chose to stay in the machine.

“So people don’t seem to be seeking only pleasure,” De Brigard says. “Nozick is right. But the experiment doesn’t suggest that people are valuing reality either. What I suggest is that people tend to value the status quo; they value the life they know, whether it’s real or not.”

But De Brigard doesn’t say that all people value the status quo. He says his experiment simply shows that philosophers should think twice before suggesting that all humans value one thing over another.

Another implication, he says, is that philosophers should be careful when using thought experiments — especially when the concept in question can be tested.

Consider one of Knobe’s favorite topics: intuition. Knobe says that some philosophers think about what a person’s ordinary intuition would be in a given situation and come up with a theory.

“But then experimental philosophers go out and check that ordinary intuition,” Knobe says, “and sometimes it’s the opposite of what the philosophers thought.”

He also says that experimental methods make it possible to do things that philosophers could never do in their own heads. X-philes can concoct experiments to study how people of different cultures view intuition. They can study how young children feel about certain concepts. They can look at how quickly people answer different kinds of questions. They can make correlations between a person’s moral views and moral judgments.

“So, maybe there’s a certain distance you can go inside your own head,” Knobe says. “But there’s an extra distance you can go when you take to the streets.”