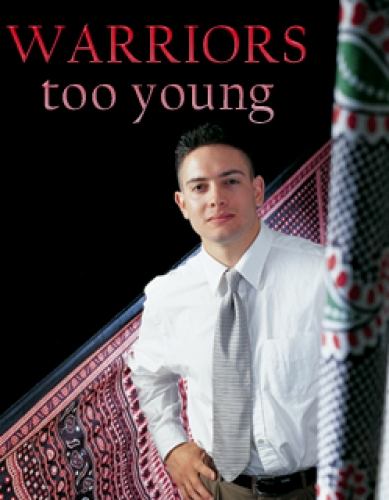

How’s this for a summer holiday: six weeks in East Africa’s largest slum, living amid open sewage, abject poverty, and frequent riots; contracting a mild case of malaria; and often feeling imperiled. That’s just what Rye Barcott, who graduates from Carolina this May, endured last summer while conducting field research on youth culture and ethnic conflict in Kibera, outside Nairobi, Kenya.

You might think that Barcott would never want to clap eyes on Kibera again, but he plans to return for three months this summer. It’s not that he’s inured to the hardships and dangers of Kibera—it’s that Barcott has resolved to help Kibera’s young people pull themselves into a better life.

How does a guy from Rhode Island develop a passion to aid people half a world away? The impetus was 1994 TV reports of genocide in Rwanda; the perpetrators were largely young males between 15 and 25 years old, and Barcott couldn’t fathom how people his age could engage in something so horrific. “I remember being glued to the TV and wondering how it could happen,” Barcott explains.

At Carolina, he seized all opportunities to satisfy his curiosity about conflict, conflict resolution, and Africa. He pursued bachelor’s degrees in international studies and peace, war, and defense, and studied Swahili. He was involved with the Triangle Institute for Security Services, editing a manuscript, “Conflict in Africa,” with Carolyn Pumphrey, the institute’s program coordinator. With Jim Peacock, professor of anthropology, and graduate student Carrie Miller, he authored the American Anthropological Association’s statement on ethnic cleansing.

In 1999, he was selected as one of five Burch Fellows and decided to use the fellowship to conduct field research in Rwanda. “I wanted to understand the cause of ethnic conflict,” Barcott says, “and for that I’d need to study youth culture.” Shifts in Rwandan politics forced him to change his plans. “Since I speak Swahili, I wanted to make sure that I was somewhere in East Africa,” Barcott explains. He settled on Kibera—a 620-acre conglomeration of huts that 1.3 million people call home.

When he arrived in May 2000, Kenya was emerging from its worst drought in recorded history. “It was total chaos—much worse than I’d expected,” Barcott says. “Most Kibera residents thought I was crazy to have left prosperous America for Kibera and wondered what they could get from me.”

A Good Samaritan deed made life a bit safer. “During my first week there,” Barcott recalls, “I was in Nairobi and spotted a mob surrounding a man and accusing him of theft.” He managed to escort the man to safety. As luck would have it, the man’s brother is the leader of one of Kibera’s strongest gangs. An ensuing acquaintance with the grateful gang leader gave Barcott a bit of protection. Even so, life was never a lark.

“I was mugged twice,” Barcott says, “and there were a lot of confrontations because I was the lone white person, and people were suspicious of my motives.” He gained a modicum of security because his ability to speak both Swahili and Shen’g made him an enigma to the slum dwellers. (Shen’g is slang devised by young slum residents that’s part Swahili, part mother tongues, and part American rap lyrics.) For an extra measure of safety, he moved between four friends’ homes, never staying more than a few consecutive nights in one place.

His plan to collect information through interviews proved problematic. Many viewed his research as exploitation of their plight, and some of his most willing participants just wanted to convince him that they were worthy of charity. He managed to interview 126 people, mostly young males. He asked about his subjects’ origins (many residents had left small villages in search of a better life), worldview, ethos, and aspirations. From interviews with their elders, he learned something of Kibera’s history. Surprised by the low regard his subjects had for nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), Barcott added a third component to his research: an assessment of the efficacy of NGO programs.

NGOs, which are funded by private donors or other governments, are the residents’ only hope for emergency relief or developmental aid. (According to official government maps, Kibera has no inhabitants and therefore doesn’t receive government services.)

“Because people are so tightly packed into small huts and children play beside open sewage and garbage,” Barcott explains, “Kibera is a public health concern.”

“My course work and extracurricular projects formed a strong framework for my field research,” Barcott says. “But I didn’t realize how ineffectual NGOs can be—some even use the slum residents’ situation for their own gain.” He identified many NGO problems, including annual shifts in leadership (and consequently, in focus) and failure to include slum residents in the organization.

Barcott believes that NGOs should “help prevent conflict” rather than primarily address its aftermath “because that’s costly and often has unintended consequences.” He was impressed by a sports association in another slum that gave young people structured activities, required community service, and espoused a positive ethos that was absorbed by the kids.

After his return to Chapel Hill, Barcott pored over his research while writing his senior honors thesis and teaching a class on ethnic cleansing as part of Carolina Students Taking Academic Responsibility through Teaching. He was struck by the residents’ high regard for education—many parents will do anything to pay school fees because they see education as a way out of the slum. In the absence of free public education and employment opportunities, young people are left idle and hopeless—easy targets for manipulation. “Young males are used by political candidates to crush opposition and rally support,” Barcott explains. “But they have to be instigated—from my experience such activities didn’t originate with the young people.”

Barcott has created Carolina for Kibera, a nonprofit charitable corporation, to draw attention to the slum’s problems. He hopes to raise money and awareness with an exhibition at Carolina of photographs taken by children in Nairobi’s Mathare slum.

Last summer he used $400 to fund a microcredit loan program aimed at Kibera’s young people. If he secures funding, Barcott wants to help develop that NGO, as well as a sports association and a nursery school when he returns to Kibera this summer.

“I think,” Barcott says, “the projects have a thirty percent chance of success and every step will be a struggle. The real challenge will be to instill an enterprising spirit in the leadership.” It’s a challenge he’s eager to tackle. “I have a long-term commitment to Kibera,” Barcott explains. “I made a lot of friends, and even though it was tough living, I really liked the place.”

Janet Wagner was formerly a staff writer for Endeavors.