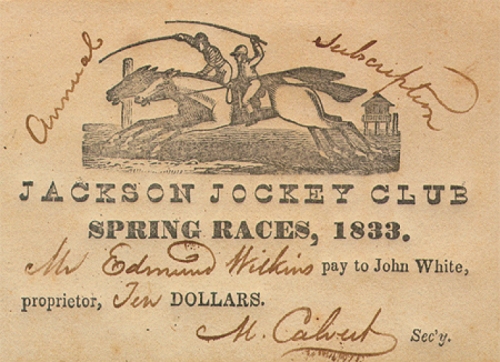

Long before Kentucky, Maryland, and New York held the Triple Crown, the Carolinas and Virginia were among the horsiest states in the Union. In fact, horse races were once the most popular sporting events in North Carolina, says Neil Fulghum, keeper of the North Carolina Collection Gallery.

North Carolinians were so fond of going to the tracks that the colonial government passed a statute in 1764 to curtail gambling “at any Game or Games,” with only two exceptions: backgammon and horse racing. Newspapers began criticizing government officials for spending too much time at the tracks and not enough time on their public duties. Of James Turner, North Carolina’s governor in 1803, The North-Carolina Minerva wrote, “Will the People be benefited if the Governor has the fastest horse?”

John Brickell, an Irish physician transplanted to North Carolina, described the colony’s racing scene in 1737:

.they have Race-Paths, near each Town, and in many parts of the Country. Those Paths, seldom exceed a Quarter of a Mile in length, and only two Horses start at a time.These Courses being so very short, they use no manner of Art, but push on with all the speed imaginable.

Over time, race distances became longer, up to four miles. Good jockeys became famous, among the first sports heroes of a new nation. Some of those heroes — such as Austin Curtis, considered the best jockey of his time — were slaves.

By 1790 the General Assembly had decreed that anyone convicted of the theft of “any horse, mare, or gelding..shall suffer death without benefit of clergy.” The punishment’s severity, Fulghum explains, reflected the growing number of refined and expensive horses to be found in the South.

But Northerners had their own fast horses. And the rivalries were getting hot. “Long before their respective armies faced one other, the North and South were already at war on the race track,” Fulghum says.

In 1823, Southern Colonel William Ransom Johnson issued a $20,000 challenge — a monstrous sum at the time — to Northern horsemen. Johnson chose a North Carolina chestnut, Henry, to represent the South.

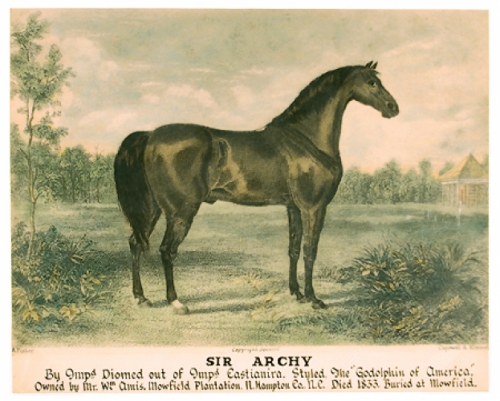

Henry, bred in Halifax, N.C., was the son of Sir Archie, another Virginia-Carolina horse and the equine superstar of his day. It’s said that in one race Sir Archie so far outdistanced the rest of the field that he walked over the finish line in first place. One day at the Scotland Neck track he ran a four-mile heat in a blistering 7:52 — an average speed just over 30 miles per hour — and was immediately bought and retired to stud by General William Davie, one of the chief founders of the University of North Carolina. “The bloodlines of many later champions, among them Man O’War and Secretariat, can be traced back to Sir Archie,” Fulghum says.

Sir Archie’s son Henry faced the North’s horse, Eclipse, on May 27, 1823, in Long Island, New York. Sixty thousand people turned out — more than the population of New York City at the time. The horses ran three heats of four miles each, which Fulghum compares to a modern horse running nine Kentucky Derbies in a single day.

Henry took the first heat. Then Eclipse’s manager decided to change jockeys, giving the reins to Samuel Purdy, a 38-year old retired jockey who had merely been at the race as a spectator. Eclipse then won the second heat.

Fulghum says Henry’s manager Colonel Johnson overindulged on lobsters the night before the race and got so sick that he couldn’t make it to the track. Johnson’s substitute manager decided to replace Henry’s jockey — “the white boy John Walden” — with Johnson’s head trainer, Arthur Taylor, for the third and final heat. Eclipse took heat three, along with Johnson’s $20,000, leaving many to lament “that a plate of lobsters had cost the South the championship of the turf.”

By this time, breeders had begun calling the Old North State — particularly Northampton, Warren, and Halifax Counties — “the race-horse region of America.”

“North Carolina has all the advantage of both the North and the South, without the disadvantages of either,” wrote Wake County’s B.P. Williamson. “Here horses may be run out all the year round, shelter being necessary but only a few days in midwinter.” Williamson described Carolina’s air as “dry and pure, with a bracing effect on the lungs.”

But by the 1850s, horse racing’s popularity in North Carolina was beginning to decline. Breeding and competitions increasingly centered on today’s hotbeds: New York, Maryland, and Kentucky. The Civil War further crippled racing in the South as money dried up and breeding stock was lost. In 1942 the North Carolina legislature reined in horse racing and gambling, making them illegal in the state.

As recently as 1993, the legislature considered re-establishing horse racing and allowing betting on races, and even put forth a bill to establish a state horse racing commission. Concerns about animal rights and commercial gambling ultimately quashed the bill.

Yet horse racing has never been far from Carolinians’ hearts. Stock car racing, Fulghum says, just might be Southerners’ modern mechanized expression of love for the horse track. Still, Fulghum says, few people today appreciate the deep passions that racing stirred in our ancestors, back when the Sport of Kings reigned in our state.

Fulghum put together “The Sport of Kings,” an exhibit that ran in the North Carolina Collection Gallery from January through March 2002.