George W. Bush has his plate full.

As if the staggering array of duties facing any U.S. president weren’t enough, Bush also has undertaken a war on terrorism, a campaign for heightened homeland security, and the resuscitation of an economy shocked to its foundations on September 11.

He’s going to need help.

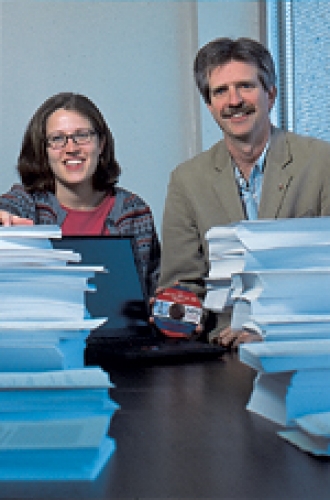

That’s where Terry Sullivan, associate professor of political science, and seven of his Ph.D. students come in.

After three years of work, they announced this February the completion of Nomination Forms Online (NFO) — new computer software that simplifies and speeds completion of the many forms that presidential appointees must submit before they can be approved for government work.

The software replaces a paper-and-typewriter method that befuddles even the sharpest of accountants, slows appointments, and discourages qualified experts from government service.

NFO is good news for the administration, which so far has only about 450 appointees cleared and on the job. Even in the best of times, the government needs some 7,000 appointees. Now more are expected for the war and for homeland security.

In the past, nominees have sent forms to the White House an average of four times before getting them right, Sullivan says. “These forms request the same information repeatedly, and the same information presented in different ways. Nominees must sift through their records over and over, reshaping the information for the newest inquiry.”

NFO changes all that. Nominees may download NFO for free to their computers, where the forms they complete can remain private. NFO identifies which forms must be submitted for the job in question, then automatically transfers redundant information — name, address, Social Security number — to all of them.

The software also answers similar questions by customizing information provided by the nominee and applying it to the appropriate questions, searching some 1,700 separate questions nominees might answer. And corrections don’t require starting over on a new paper form. Nominees need only to edit on computer and push print. They can save the information on their computers in case they are nominated for future positions.

The work is part of White House 2001, a project headed by Martha Kumar, a political science professor at Towson University in Maryland, with Sullivan as associate director. “We both come from public universities, so we wanted to find a way for scholars on the presidency to be involved in public service,” Sullivan says.

While Sullivan took on the software idea, Kumar headed the White House Interview Program, which collected 80 interviews with people who had worked in the White House, plus related essays by scholars. The interviews were designed to help new White House staffers learn what would be expected of them before they began their new jobs, which were often nothing like their previous jobs and twice as fast paced.

The software project began with groundwork by Stephanie Haas, associate professor of information and library science. Haas and a graduate student gathered all the forms, analyzed the information each requested, identified where duplication and overlap occurred, and considered how the forms could be completed most efficiently.

Sullivan and students took it from there. Code for the software was written by Boston Educational and Software Technologies of Mumbia, India, and Infinity Software, a Boston subsidiary in Florida.

Even before the software was finished, the students helped federal officials understand the forms and revise those the White House controls, reducing information overload by about 30 percent. Now, NFO will boost that reduction to 40 percent.

“These students have played a critical role in developing the software and updating information about questions when the government changed forms — five times during our project,” Sullivan said. “They did all the user testing on twenty-eight versions of the program before it was released.” The students, all in Carolina’s political science doctoral program, are also staffing a help line for software users, coordinated by student Jennifer Hora.

In addition, the project sparked legislation now before Congress to make it simpler for nominees to make required financial disclosures. Now, Sullivan and Kumar are editing a book due out this fall that will collect and summarize the accomplishments of White House 2001.

Funding for White House 2001 came from the Pew Charitable Trusts of Philadelphia through the Brookings Institution and the American Enterprise Institute. “This is a success story in which private philanthropy mobilized the academic community to help government work better,” Sullivan said. “For a public university, this project is what our mission is all about: using knowledge to solve public problems.”

L.J. Toler was formerly a staff contributor for Endeavors.