Cuba: Picturing Change. By E. Wright Ledbetter, with essays by Louis A. Pérez, Jr., and Ambrosio Fornet. University of New Mexico Press, 216 pages, $39.95.

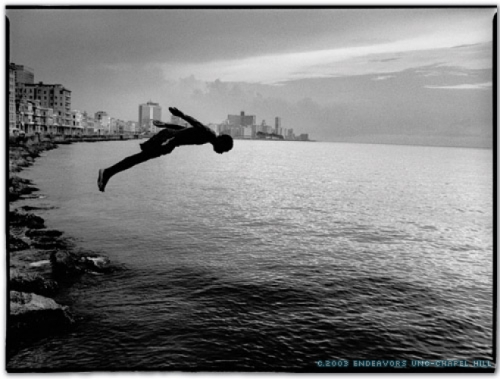

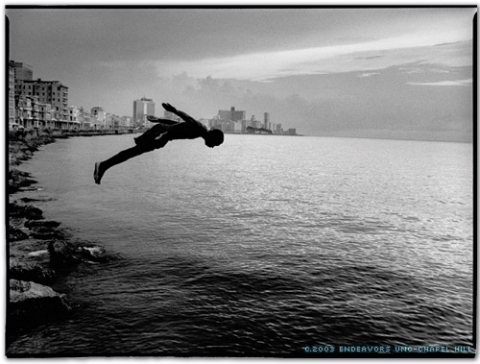

The boy flies. His body not quite horizontal, his arms thrust out and back. All we get in this silhouette is the white of one upturned palm, the soles of his feet, the pocket lining of his swimming trunks. Behind is the coastline of Havana, running from the boy’s head down his spine and then out of the shot; below is the sea. The boy is no longer leaping — rotate him just a quarter turn counterclockwise and he’s standing on tiptoe, maybe at the water’s edge — but he isn’t diving yet, either. He simply flies, lingering over an ocean that, for better or worse, holds his future.

The boy is Cuban, and in some ways, Cuba. This photograph, writes renowned Cuban author and screenwriter Ambrosio Fornet, is a metaphor for a moment of transition: “what hangs in the void like a giant question mark is Cuba’s immediate fate.” It’s the cover of Cuba: Picturing Change, a book of E. Wright Ledbetter’s large-format photography with essays by Fornet and Louis Pérez, Jr., professor of history at Carolina.

These are not the bright images of cozy architectural decay and dashingly mended old American cars one expects in photographs of Cuba. Ledbetter turns his lens to Cuba’s people, who shine through his stark blacks and whites. A boy spins a top on his palm. Children line up for a slide. A dog waits on the street corner. Men play dominoes. A rabbi looks up from his desk.

“In this work I have tried to examine the compassion and sense of hope of the Cuban people,” Ledbetter writes. “I have tried to portray the determined rhythms of the Cuban culture, where we may see joy, peace, and individual strength, but where we may also find insecurity, uncertainty, and vulnerability. I believe — and a number of these photographs reflect this — that Cuba is on the verge of a new ‘revolution,’ and barring substantial political and economic reforms, the Cuban people will be mostly subject to, rather than a part of, any changes that may ultimately occur.”

Change is embedded in the condition of being Cuban,” Pérez writes. Those changes can come in the form of natural forces such as hurricanes, or market forces — “where the fluctuation in the world price of sugar by a mere penny or two signaled the difference between dazzling prosperity and abject poverty.”

Ledbetter’s photos, writes Pérez, suggest the vitality of a people and place in a time of transition. “These are ordinary people during extraordinary times,” Pérez writes, “without illusions, without self-deception, but always with self-possession, focused on change and the future — again.”