The sign in the parking lot reads Carrboro Municipal Parking Lot/Estacionamiento Municipal de Carrboro. Until recently, your eyes would skip over the Spanish. Now you notice. The fishing-supply store you’ve jogged past for years now also houses a Mexican tienda. Several streets away, Latino men line up each morning at an informal labor exchange. A Latino man passes you at the bus stop on his way to work every morning and always says hello.

Yes, you’re beginning to notice: You live in the midst of an alternate universe. The world of our Latino neighbors is often largely invisible to many long-time North Carolina inhabitants — except when news of policy changes, jobs, or residential conflict brings it to our attention. But Altha Cravey draws you through the “parallel door” that leads into that world.

In much of her current work, Cravey spends time with Latino immigrants in bars, dance halls, flea markets, private homes, and apartment complexes — local social spaces created and appropriated by Latino immigrants. Cravey, associate professor of geography, has made lots of friends, and in the process she’s collected many stories. “You collect so many that you begin to have themes,” she says. “Then you try to get people to understand through that collection of stories.”

The Scale of Daily Life

What does Cravey want people to understand about Latino immigrant communities? That individual lives are microcosms of globalization. Latino immigrants — about 75 percent of whom are Mexican in North Carolina, Cravey says — stretch their lives across borders, making temporary and unusual living arrangements that keep costs down, redefine gender roles, and substitute for personal relationships and services they might have left behind in their home countries. In a paper published in the June 2003 issue of the geography journal Antipode, Cravey argues that the flexibility and fluidity of Latino households make globalized labor markets possible.

For example, Latino men, separated from their families, often live in large groups in an apartment or house, splitting the domestic chores and duties. Through such arrangements, the men save money and blur the boundaries of gender. “Not only are men dividing up the cleaning of the household, but they’re each other’s immediate emotional resources, too,” Cravey says. “I see it in terms of friendship and camaraderie, but also in terms of hostility, the working through of tensions.” Sometimes, in dance halls and bars, there are fights. “It seems like what I’m seeing is that painful situations they may have during the day get worked out with their buddies or somebody they don’t know.”

Cravey says that the temporary and fluid domestic and social arrangements constructed by Latino immigrants save money for North Carolina — and the United States — as well. This has to do with social reproduction, which Cravey defines as the costs of caring for and sustaining ourselves as human beings — biological and emotional needs, health care, schools, and social spaces.

Cravey argues that often these costs aren’t paid by the United States. When immigrants raise their children in their home countries, then send them to the United States to work, the U.S. benefits from a relatively low-wage adult workforce. While here, workers may be separated from their social networks and may not have access to services such as health care, which is more affordable and partially collective in Mexico. But, due to close ties back home, “When they come here and work in some kind of crummy job, they’re still thinking in terms of the network back home and expectations back home,” Cravey says. She knows a family in which three generations have worked in the United States, returning home to raise their children.

Immigrants’ domestic and emotional sacrifices — the reorganizations and risks of their lives — benefit North Carolina employers, Cravey argues. The U.S. economy has come to rely on an international flow of labor, just as the cross-border wage gap has made crossing the border for work an economic necessity for many people from Mexico and other Latin American countries. Cravey has heard the claim that workers can make as much in North Carolina in a single day as they can at home in a week. “There are great success stories,” Cravey says. “That’s part of what fuels the urge to go.”

Immigration Isn’t New

From 1990 to 2000, according to U.S. census figures, the Hispanic population in North Carolina increased by 394 percent to about 379,000, making North Carolina the state with the fastest-growing Hispanic population in the country during that period. North Carolina’s Hispanic population officially grew another 16 percent to 440,000 by 2002, recent census figures indicate. And Cravey says that though the Census Bureau tried many strategies to avoid missing Latinos — such as multilingual census-takers who went to community fairs, job sites, and residential areas — there was certainly some undercount. James Johnson, professor of management and director of the Urban Investment Strategies Center at the Frank Hawkins Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise, says accounting for the Hispanic undercount in the 2000 census would bring the total to about a half million in North Carolina that year.

Latino immigration to North Carolina is not a new phenomenon, Cravey says. Data show a steady increase beginning in the late 1980s, when usage of the federal H-2A program — a special visa program for temporary foreign agricultural workers, which currently brings about 10,000 Mexican workers to North Carolina annually — shifted from Caribbean to Mexican workers, and other sectors of the economy such as poultry and meat processing began to open up the Southeast to Latino workers. And during the economic boom and tight labor market of the 1990s, employers began using informal networks such as interstate and cross-border advertising and recruitment to attract migrant workers to the state.

But there has certainly been some acceleration in the influx, Johnson says. “You get a threshold population,” he says, “and then the friends-and-neighbors effect kicks in — networks of family and friends from distant locations begin to migrate to the same kinds of communities.”

Cravey says that formal labor markets such as H-2A also encouraged informal flows in other industries such as poultry processing, Christmas-tree and wreath production, entry-level hotel and restaurant service, construction, and landscaping. Employers in these sectors have come to rely on Latinos, who often perform low-paying and dangerous tasks in these jobs. According to figures from the Raleigh-based Latino advocacy group El Pueblo, 95 percent of North Carolina temporary agricultural workers and 50 percent of workers in meat-processing plants are Latino. In 2002, Nolo Martínez, then director of Hispanic/Latino Affairs in the Office of the Governor, found that 95 percent of construction jobs in Charlotte and 90 percent of construction jobs in Raleigh were held by Hispanics.

As part of a broad study of North Carolina’s fast-changing furniture industry, Meenu Tewari, assistant professor of city and regional planning, has found examples that contradict common stereotypes about immigrant workers.

“The surprising thing that I found was that the origin of the shift in the furniture industry toward hiring more immigrant workers predated NAFTA,” she says. From interviews with local and state officials, Tewari found that this change in the workforce began in the early nineties, partly because of efforts by local officials to attract other types of businesses to the High Point region. Young residents were drawn away from furniture factories and into slightly higher-paying office jobs, and some furniture companies actually faced a tight labor market. “That’s when the industry initially began to look for workers from across the border,” she says. Tewari interviewed one worker at Bernhardt Furniture who said that Hispanic immigrants were not taking jobs away from residents; they were reducing an overwhelming work load.

More Than Workers

The Bush administration’s proposal early this year of a new temporary worker program brought attention back to immigration reform. This proposal would grant new foreign workers and undocumented immigrants currently in the United States temporary worker status for a three-year period. In theory, employers would fill jobs with temporary workers when they could find no U.S. citizen to fill them. While it would give certain rights to the undocumented, the proposal leaves many unanswered questions, Johnson and others say. How can employers determine there is no U.S. citizen who “wants” jobs? Would the worker be bound to one employer, unable to seek other opportunities if that employer goes out of business or treats workers unfairly? Would the worker be able to bring his or her family to the United States?

“Immigrants cannot be treated as isolated workers,” says Krista Perreira, assistant professor of public policy. “They are social beings who are members of families and communities.” To be successful, policies and programs that target new immigrants should be grounded in an understanding of their experiences in their countries of origin and in the United States, Perreira says.

It may take a while before any immigration reform will become policy. In the meantime, the President’s proposal is not the only one being discussed. Another, the AgJOBS bill, is currently in debate in the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. AgJOBS would only apply to farm workers, but it includes a mechanism for workers earning lawful permanent resident status based on how long they have worked in agriculture in the United States. It also would allow a farm worker to bring his or her family, who can adjust to lawful permanent resident status when the farm worker does. A broader version of the AgJOBS bill, not confined solely to agricultural jobs, is also pending.

Health Care Needs

Many male workers are now coming to the state with their families, says Guadalupe Ayala, assistant professor of health behavior and health education in the School of Public Health. Ayala was drawn to North Carolina by the influx in the Latino community. “What I saw in the census data was a trend toward more migration of women and children,” Ayala says. “To me that said something about the health-care needs of the community, which is in real transition. We know that men often don’t seek health care for themselves, but women will seek health care for their children.” In the last few years, she and other public-health faculty and students have been conducting research on the immigration and acculturation process — studying how individuals and families respond to their new environment as well as how the environment changes in response. They work with community organizations and advocacy groups, health-care providers, and members of the Latino community to evaluate cultural, language, and other barriers in the way of accessing health information and care.

In one recent study, Ayala and health behavior and health education graduate student Amanda Phillips-Martinez found that members of the Latino community in Durham accessed health-care services more at the end of a two-year period than they did at the beginning, due in large part to outreach work by community organizations and word of mouth within the community. They also found a widespread desire among health-care providers to learn Spanish.

Other projects include evaluation of the effectiveness of people known as “lay health advisors,” people who communicate health information to their peers. Ayala has conflicting opinions about this. “Using lay health advisors places the responsibility of appropriate information and education on lay people, and we have health-care systems that are supposed to be taking care of that,” Ayala says. But the practice seems to be relatively effective, and until existing systems can meet the needs of Latino communities, such alternative methods must fill the gap.

The Dream of Education

But a need even more pressing than health care, Ayala feels, is the Latino community’s access to education. Perreira agrees. “I believe that we must help our youth graduate from high school and attend college,” she says. “For Latino youth from low-income families, the high cost of college and limited availability of financial aid are significant barriers.” Perriera is a member of the North Carolina Society of Hispanic Professionals, whose main charge is to help educate youth. Within that organization, she has been working to found a scholarship fund for Latino youth who graduate from high school and are admitted to college.

But many Latino youth may be ineligible to attend college. Foreign-born children of immigrants — whether they’re permanent residents, other lawfully present non-citizens, or undocumented — can attend elementary and secondary school in the United States. But once they graduate from high school, their formal education may end. If they are not U.S. citizens, they cannot apply to U.S. colleges without returning to their home country, getting a student visa, and paying out-of-state tuition — even if they’ve lived here most of their lives and their families plan to stay in the United States.

Often students drop out of school and start working, Ayala says, or go back to their country of origin while their parents stay in the United States. Matt Griffin, a graduate student in health behavior and health education, works with a Latino youth organization in Durham. One of their projects raises awareness about the DREAM Act, a bill that’s been introduced into Congress that would allow students a six-year window of temporary residency in order to attend college.

Of course, pre-college education has its challenges, too. James Johnson gives talks on recent demographic change to employers, school districts, and educational associations across the state.

“They are interested in what schools are going to look like in the years ahead,” Johnson says. “But I take it beyond that and talk about the implications of the impending demographic change, from the achievement gap to the new imperative to globalize the public-school curriculum, internationalize the faculty and staff, and incorporate diversity-sensitivity training for all staff and administrators because of cultural differences.” And Maria Teresa Palmer, a Rockefeller fellow at Carolina’s University Center for International Studies, uses research she did with Latina immigrant high school students to present workshops to area teachers on the needs of immigrant students. She also serves on the N.C. State Board of Education.

Communities of Faith

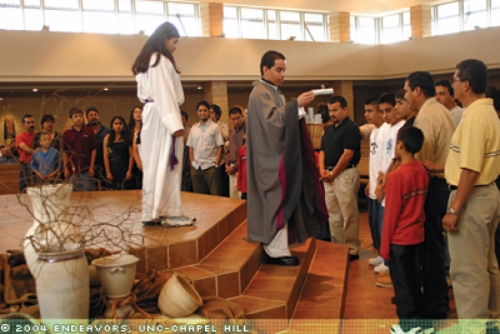

Often bridges to diversity can be found in churches. North Carolina, traditionally a state with an overwhelmingly Protestant population, has been dramatically transformed in the last decade or so, says Thomas Tweed, professor of religious studies and adjunct professor of American studies. In an essay published in the Summer 2002 issue of the journal Southern Cultures, Tweed writes that North Carolina contains two of the four U.S. dioceses with the largest percentage of growth among Hispanic Catholics — Charlotte and Raleigh. “At first well-intentioned Catholic leaders were surprised, maybe even caught off guard, by Latino migration into the state,” Tweed says. But now Spanish-language Catholic masses and Spanish-speaking priests have begun stepping in to meet the need.

Tweed says Latinos in the state are also affecting other denominations, including Protestant and Pentecostal churches, some of which have begun offering Spanish-language services. One, the United Church of Chapel Hill (Iglesia Unida de Cristo), holds a service for Spanish speakers led by Pastora Maria Teresa Palmer. “As pastor of an immigrant church, I strive to create a faith community where nobody feels ‘foreign,’” Palmer says. “It is a privilege to help folks become part of our community.”

New immigrants’ spiritual and social needs are often met by church communities, Tweed says. “In churches, immigrants can make sense of themselves as individuals in a community,” Tweed says.

The Civil Rights of Immigrants

Hiroshi Motomura, professor of law, says he came to Carolina from the University of Colorado last year to be in the middle of “the crucible” for determining the relationship between immigrant rights and civil rights. “North Carolina comes from a long tradition in the last couple generations of struggles over civil rights,” Motomura says. “You have new populations trying to find their place in a framework of civil rights that has been established in a black-white context. Will Latino groups and traditional African-American groups align and find common cause as people of color, or will there be tension or even a divide based on citizenship status or language?”

Are immigrant rights civil rights, or are they different? “That to me is the challenge for North Carolina,” Motomura says. “Clearly there are differences on the surface, because you are often talking about people who aren’t citizens of this country. And yet to the extent that the civil rights movement embodies broader values about human rights, dignity, and integration into society, then it’s the same thing — especially when you consider that the U.S.-born children of all these immigrants will grow up here as U.S. citizens themselves, whether their parents are here legally or not.”

Motomura has served as co-counsel or volunteer consultant on federal immigration cases. He is writing an interpretive history of the last 200 years of U.S. immigration and citizenship law. His book is entitled Americans-in-Waiting: The Lost Story of Immigration and Citizenship, because, he says, “We used to treat immigrants much more as if they intended to become citizens. It used to be that if you filed a declaration of intent to become a citizen you could vote, for example. And my argument is that we can and should revive the notion that immigrants are Americans-in-waiting.”

North Carolina’s Future

James Johnson, who came from Los Angeles, says that North Carolina is facing many of the same race- and immigration-related issues that city faced fifteen years ago. “But I think this state has made a concerted effort to manage it better,” Johnson says.

One example is North Carolina’s Durham-based Latino Community Credit Union, which operates five branches statewide. Keeping a bank account is the first step toward building credit. But national statistics show that, as of 1998, 25 percent of Hispanic families had no bank account, compared to just 5 percent of white households. Michael Stegman, chair of public policy and director of the Kenan Institute’s Center for Community Capitalism, cites Federal Reserve data showing that 18 percent of people without bank accounts say that they just don’t like dealing with banks.

Some Hispanic people, for instance, may be wary because in many Latin American countries the banking system is unstable. And Hispanics also deal with language barriers at many banks. But without bank accounts, families can be forced to pay high fees to check-cashing outlets and other fringe banking services. And, as Stegman told Congress in 2000 while testifying about legislation that would help bring more people into the banking system, people who have bank accounts are more than twice as likely to have money saved than those who don’t have accounts. The Latino Community Credit Union, established in 2000 and only the second credit union in the Southeast geared toward Latinos, helps address some of these problems.

In addition to many active Latino-community-based organizations, Johnson points to the state’s Office of Hispanic/Latino affairs within the Office of the Governor and the UNC-system affiliated North Carolina Center for International Understanding, which operates a program that takes philanthropic, business, governmental, and school leaders to Mexico for cultural immersion programs. He also sees a quiet development in voter mobilization, the proliferation of English as a Second Language classes in schools and workplaces, and the formation of political coalitions between African Americans and Latinos around common issues such as quality of education, housing, and jobs.

“I think in some communities where there used to be tensions over the influx of Hispanic newcomers, now you’re seeing efforts to build a bridge,” Johnson says.

He describes strong family ties among Latinos, high business-formation rates, and home-ownership rates higher than those of natives. “I don’t think we’ve had a full cost-accounting of the contributions that Hispanic immigrants make to our society and our economy.” Johnson says. And the American native population is “graying,” he adds, so immigrant worker-power will be essential to the country’s future competitiveness. Recent Census Bureau projections predict that the U.S. Hispanic population will rise from 12.6 percent of the country’s population in 2000 to 24.4 percent by the year 2050.

“The question becomes, how do we replace the aging baby-boom generation?” Johnson asks. “The population is going to be exiting the labor market since we have a baby bust behind it. The only way you can do it is through immigration.”

Michelle Coppedge was formerly a staff writer for Endeavors.

Ayala’s work is funded by the Department of Health Behavior and Health Education and UNC-Chapel Hill’s Program on Ethnicity, Culture, and Health Outcomes.

Starting in fall 2004, Carolina will offer a transdisciplinary undergraduate minor in Latina/o studies — the first such minor in the Southeast — which is directed by María DeGuzmán, assistant professor in the Department of English.