Three things come to mind when thinking nuclear — energy, weapons, and potential catastrophe. What about earthmoving? Seriously, that’s exactly what American scientists were thinking between 1957 and 1974.

Scott Kirsch details this Cold War corollary in Proving Grounds: Project Plowshare and the Unrealized Dream of Nuclear Earthmoving.

Led by physicist Edward Teller, often called Father of the H-Bomb, Plowshare scientists thought they could use nuclear bombs to create a new canal in Panama or Colombia. The Army Corps of Engineers estimated that three hundred buried nuclear bombs along a forty-six-mile corridor in Panama could do the job. The Corps said that 764 bombs would suffice in Colombia. Scientists created a map showing areas that radiation would likely contaminate.

“There was a great deal of arrogance in thinking that to do this, you have to displace thirty thousand people,” Kirsch says. “But for the most part, the weapons scientists thought it could be done safely.”

They believed in the threshold theory that said humans could withstand certain levels of radiation before causing genetic damage or diseases. “The science was debatable,” Kirsch says. “They were ignoring many of their opponents’ arguments. This was not a cautious group.”

The five-year, $17.5-million canal study was authorized by Congress, as was the entire Project Plowshare for some $750-million (in 1996 dollars) over seventeen years. “We will change the Earth’s surface to suit us,” Teller once proclaimed.

Why so gung ho?

“For some of these scientists, it was a kind of moral mission to turn the atom bomb into something good,” Kirsch says. “They were true believers.”

Another reason was financial. Weapons labs tried to diversify into other research to increase funding.

As part of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), Plowshare scientists had to receive presidential approval before each series of bomb tests. Politics at the national level, then, played a big role in the eventual demise of nuclear earthmoving. But even more important, Kirsch argues, was that the program’s risks and hazards generated opposition among a wide range of scientists and activists from Alaska to Australia. Such opposition wound up galvanizing the environmental movement in important ways.

For example, Plowshare scientists proposed the creation of a harbor at the mouth of a small stream on Alaska’s northwest shore. The AEC wanted to plant five atom bombs totaling 280 kilotons. Newspaper editorialists and a senator from Alaska were initially swayed by Teller’s argument that fallout would be contained. Many University of Alaska scientists and others were unconvinced. They studied the area and plans at the AEC’s request. They filed reports showing potential radiation side effects. The AEC buried the reports, Kirsch says. “So the scientists made an end run.”

They contacted activists, other scientists, and government officials. The local Eskimo population lobbied Native American rights groups and the Department of the Interior. The project was shelved after five years.

“We need to remember these stories of technological failure,” Kirsch says, “because they don’t just happen. There are critical lessons about the relations between science and democracy, the way science is processed by the public, and the ways in which we deal with uncertainty and risk.”

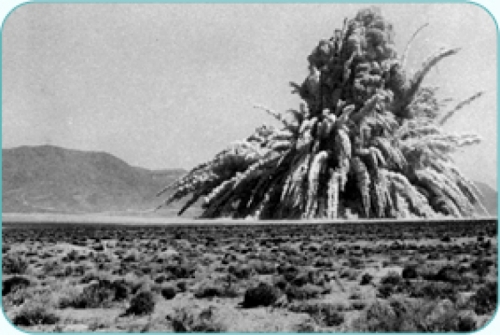

Project Plowshare, then, remained limited to the Nevada desert, where scientists exploded twenty-seven bombs. The largest and most infamous was Sedan. Scientists planted a 104-kiloton device 635 feet below ground. It left a crater 1,280 feet across and 320 feet deep that remains a popular tourist attraction today despite above-normal radiation levels. In all, the AEC detonated 928 bombs from 1951 to 1992 in Nevada.

Is it safe? “I wouldn’t go camping there,” Kirsch says.

Proving Grounds: Project Plowshare and the Unrealized Dream of Nuclear Earthmoving. By Scott Kirsch. Rutgers University Press, 257 pages, $39.95.