In most Southern cities just after the Civil War, black residents were still second-class citizens. Wilmington, North Carolina, was an exception in some ways. Black-owned businesses were on the rise — though by no means dominant — in the local economy. But in 1898 in Wilmington, a powerful statewide campaign of white supremacy and hatred culminated in murder and the destruction of the only black-owned newspaper in the entire country. Following the violence, blacks in Wilmington lost the right to vote. The age of Jim Crow — where signs would direct foot traffic through the doors of racially segregated theaters and train cars for years to come — started right here in North Carolina.

All of this happened with the help of some of today’s most popular North Carolina newspapers.

Last fall, they asked Timothy Tyson to help them apologize — in print.

Tyson’s education in race and history started long before college. His father, a Methodist preacher, moved the family several times around eastern North Carolina. Tyson lived in Wilmington from elementary school through the ninth grade. During the early 1970s, he witnessed the desegregation of the Wilmington school system, the angry mobs waving weapons and flags, and the eventual rebirth of civic discussion about race. “I had searing experiences that changed me forever in Wilmington,” he says. But the roots of this violence and tension reach much further back — all the way to 1898.

Before the elections in Wilmington that year, the conservative Democratic Party launched an intense propaganda campaign, capitalizing on already widespread racist assumptions. The party’s election strategy consisted entirely of a promise to save North Carolina from “Negro domination.” Though black businessmen did not control the local economy, major newspapers frequently ran headlines such as “Negro Control in Wilmington.” Democrats hoped to unite white voters across partisan lines.

The Democratic Party and the mainstream media also helped spread the notion that black men’s sexual aggression rendered the streets of Wilmington unsafe for white women. White supremacists insinuated that any societal advances on the part of black men were actually evidence of their sinister intentions toward white women.

Meanwhile, many white farmers had abandoned the Democratic Party over policies that they felt catered to bank and railroad interests. These defectors overcame their own supremacist leanings just enough to form a “Fusion” coalition with white Populists and black Republicans who had joined forces to pursue equal voting rights and free public schools. In the elections of 1894 and 1896, the Fusionists united around public education, local self-governance, and the right to vote. The new coalition gained a foothold in the legislature and elected their white candidate to the office of governor.

But in 1898, the Democrats stuffed the ballots, suppressed the black vote, and stole the election. Two days later, white paramilitaries took over the city. A semi-organized and heavily armed force marched through the streets, its ranks swelling as it moved. The mob burned down Wilmington’s Daily Record, the only black-owned newspaper in the United States at the time.

One group of marauders pulled a well-known black politician, Daniel Wright, from his house and beat him with a pipe. They allowed Wright to run away and chanted “Run, nigger, run!” But after Wright had run about fifteen yards, they riddled his body with close to forty bullets. We don’t know exactly how many blacks the mob killed that day, but one account tells of black bodies choking the Cape Fear River.

In the following days and weeks, Democrats threw a huge street party and settled into their newly established social order — without interruption from the state or federal government. Men who had participated in the riots were awarded public recognition and political office. Five out of six of the subsequent gubernatorial elections were won by men who had helped to organize the white supremacy campaign in 1898.

An angry mob burns and destroys Love & Charity Hall, the temporary location of Alex Manley’s Daily Record. Photo courtesy New Hanover Public Library, Wilmington, NC, ©2007 Endeavors magazine; click to enlarge.

On the one-hundredth anniversary of the white supremacy coup, Tyson and co-editor David Cecelski published Democracy Betrayed: The Wilmington Race Riot of 1898 and Its Legacy. The book included chapters by historians from all over the country.

“We tried to persuade the academics to write in accessible English,” Tyson says. “That’s some work, because you know professional scholars don’t get a lot of credit for writing for a popular audience.” Tyson wrote the book’s chapter on the white supremacy campaign through the World War II era, half a century after the riots had occurred.

Wilmington greeted the book’s publication with public discussion and performances. Churches held interracial services, citizens put on a play, and the city commissioned a monument. “This was a pivotal moment for me,” Tyson says. “It was just electrifying.” Afterwards, the state decided to formally investigate the riot.

The Wilmington Race Riot commission published their six-hundred-page report on May 31, 2006, and urged North Carolina’s newspapers to tell the truth about their involvement in the campaign.

On Friday, November 17, 2006, The News and Observer, The Charlotte Observer, and most other North Carolina dailies folded “The Ghosts of 1898” into almost 700,000 of their print editions and shipped them out all over the state. Online editors posted the insert on their papers’ web sites, where it will be available for years to come.

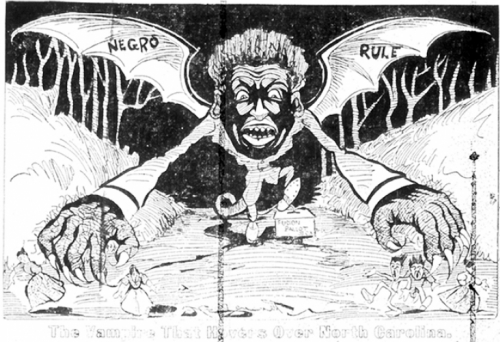

Through Tyson’s voice, the newspapers provided details of their role as engines of the white supremacy campaigns in the nineteenth century. They admitted to publishing stories that sensationalized and validated rumors of “Negro domination” and “black brutes” threatening Southern womanhood. They republished some racist headlines and cartoons of the time. One illustration by N&O cartoonist Norman Jennet showed a grotesque caricature of a black man with vampire bat wings, on which Jennet inscribed “Negro Rule.” White men and women scramble to escape the bat’s talons. Cartoons like it had frequently run on the front page in the nineteenth century.

Some readers have applauded the newspapers’ decision to publish “The Ghosts of 1898” — but not all. Letters to the editor have accused the N&O of being “obsessed with race,” while others say the insert stopped short of telling the entire racial story. One letter pointed out that the insert failed to comment on North Carolina’s Jewish community at all.

“Some people have legitimate critiques and that’s okay,” Tyson says, content with having opened a dialogue in his home state. “I just think that’s part of living in a democratic society to the extent that we do.

“It’s encouraging to see people who are kind of alive to the possibility of reconciliation and healing,” he says, “and then there’s a kind of paralysis and fear, too.”

Timothy Tyson is a faculty adjunct in the Department of American Studies at UNC. He also holds appointments at Duke University’s Divinity School, history department, and Center for Documentary Studies.