- A breast-cancer diagnostic test based on work by UNC researcher Charles Perou has been approved by the FDA.

- The test uses the genetics of some breast-cancer tumors to predict whether the cancer is likely to come back.

- In the future, doctors will be able to use the test to classify breast cancers in a new way, helping them make treatment decisions about other types of breast cancer too.

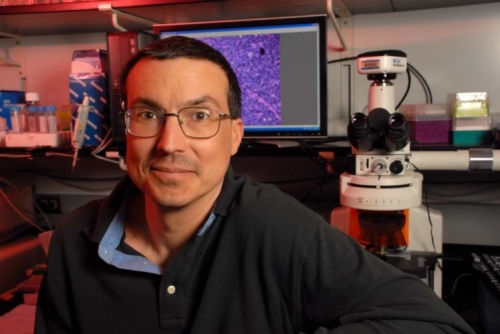

Many women with breast cancer undergo chemotherapy, but some who get it may not really need it—and some who don’t get it might benefit if they did. A test based on research by UNC’s Charles Perou can help doctors and patients decide whether to use treatments beyond surgery and hormone-blocking drugs.

The test, approved by the FDA in September 2013, can analyze genes in Stage I–III tumors to predict how likely a patient is to stay cancer-free for 10 years after surgery and hormone therapy. Tumors with certain genetic features are more likely to come back, meaning that the patient probably needs chemotherapy or other more aggressive treatments to prevent a relapse.

For years, clinical pathologists have classified breast cancers by whether the cancerous cells have estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, HER2 receptors, or none of the above. The new test, called Prosigna, is different—it’s based on 50 genes identified by Perou’s lab as being key to breast cancer. The lab divides breast cancers into four types based on those 50 genes. The four genetic types don’t always match up with the previous types based on receptors—20-25 percent of breast cancers, Perou says, have genetic profiles different from what you’d expect based on the type of receptors they have. It’s not that one test is right and the other is wrong, he says—they just provide different types of information.

He and his collaborators are still in the process of getting FDA approval to use Prosigna to classify breast cancer by those four types. It’s already approved for that use in the European Union, but right now it can only be used in the United States for the 10-year prediction of relapse in patients with hormone-receptor-positive cancer. To get the test approved as a new way for clinicians to categorize cancers, the lab is studying genetic data on thousands of old tumor samples, checking to see if their test correctly predicts how different patients responded to treatments.

For example, they’ve studied a drug called epirubicin that is typically given to women with metastatic breast cancer. Epirubicin helps some patients, but not all, and it can also have serious side effects. Perou’s lab analyzed the tumor genetics of women who’d taken epirubicin in previous studies, and found that the test could identify which breast cancers turned out to respond well to the drug.

“Breast cancer isn’t a singular disease,” Perou says. “It’s four or five diseases—maybe more.” For example, triple-negative breast cancer—the type without hormone or HER2 receptors—is genetically more like ovarian cancer than it’s like other breast cancers. Perou and collaborators on the Cancer Genome Atlas proved that last year. His lab is still identifying more genes that may be good targets for breast-cancer drugs.

“Breast-cancer treatment is already some of the most advanced in terms of personalized medicine,” Perou says. “It’s going to keep getting more and more complicated as we better understand the genetics.”

Charles Perou is the May Goldman Shaw Distinguished Professor of Molecular Oncology in the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, and a professor in the Department of Genetics and the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine in the School of Medicine. UNC collaborators on this work included geneticist Joel Parker and Perou lab research associate Maggie Cheang. Perou and others who developed Prosigna at Washington University, the University of Utah, and the BC Cancer Agency in Canada have a company called Bioclassifier LLC, which licensed the test to NanoString Technologies.