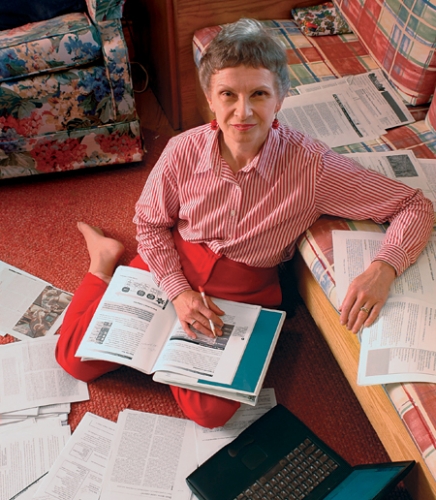

In 1990, Barbara Parker was diagnosed with two kinds of breast cancer within three months. One way she fought it — reading scientific journal articles.

“I decided that whatever happens to change things for women who have cancer, it first goes through a basic-research lab,” Parker says. “The best that science has to offer patients is an educated guess. As long as my life depended on an educated guess, I wanted to be one of the ones making it.”

Photo by Jason Smith.

Bob Millikan met with Parker once a week for about a year. His work with research participants and breast-cancer advocates “constantly reminds me of what else is out there to study,” he says.

Click to read photo caption. Photo by Jason Smith.

But all the studies overwhelmed her. Then Parker, who lives in Raleigh, met Carolina epidemiologist Bob Millikan, and she asked him if he would help her understand what she was reading. He agreed to meet with her once a week, which he did for about a year. “Bob knew the authors, knew which journals were the best,” she says. “It was exciting to have all this information in context, rather than getting it in a hit-or-miss fashion.”

Parker’s reading was the most personal of projects. But it came in handy when her interest in science went public. “I’m not shy. I hung around and made myself known,” she says. Then a researcher at Duke University invited her to join other patients who were observing scientific presentations and giving comments. That was her first step toward becoming a patient advocate.

Parker is one example of the many breast-cancer advocates who are changing how research gets done — lobbying for increased funding, helping decide what gets funded, and even evaluating research products such as drugs.

Photo by UNC Medical Illustration and Photography.

Click to read photo caption. Photo by UNC Medical Illustration and Photography.

Scientists felt the influence of breast-cancer advocates in the early 1990s, when women began fighting to get more money for research. A high-profile example was the Long Island Breast Cancer Study, which Congress funded in 1993 in response to lobbying from Long Island women who were convinced that environmental factors were contributing to breast cancer in the two counties where they lived. Marilie Gammon, now professor of epidemiology at Carolina, is principal investigator of that study, in which she led a team that interviewed more than three thousand women (both those with breast cancer and those without) and that collected blood and urine samples as well as soil and water from near the participants’ homes. The main results of that study were published in 2002. But Gammon and her colleagues continue to analyze data from the study, and recently published two additional reports (see “Clues about breast-cancer risk” in the sidebar at left).

In 1992, women helped secure money for another big research program. The National Breast Cancer Coalition steered a lobbying campaign that led to the U.S. Department of Defense creating its Congressionally Directed Medical Program in breast-cancer research. In 1993, the women campaigned more, and Congress increased the appropriation for the program from $25 million to $210 million.

As breast-cancer advocates have increased research funding, they’ve also wanted to help decide how that money would be spent. To do that, they needed to understand the science. So the National Breast Cancer Coalition created a training course to teach women scientific concepts and critical-thinking skills. Four times a year, advocates attending Project LEAD (leadership, education, and advocacy development) listen to lectures, discuss case studies, and role-play reviewing grant proposals or applications to use human subjects. Millikan, associate professor of epidemiology, is one of several scientists who developed the curriculum, and he still teaches some sessions each year.

Today, advocates serve alongside scientists on review boards evaluating research proposals for funding agencies, including the California Breast Cancer Research Program, the Department of Defense, and the National Institutes of Health.

Breast-cancer survivors are also helping to evaluate cancer drugs. Musa Mayer of New York City, for example, is an author and a fifteen-year survivor of breast cancer who, as a patient representative, serves on a case-by-case basis as a voting member of the Food and Drug Administration’s Oncology Drug Advisory Committee. She says that patient advocates can help temper enthusiasm for new drugs whose side effects may outweigh the benefits for patients. “I think we bring a very clear sense of what it’s like to actually live with the toxicities of various drugs,” Mayer says. “Metastatic breast-cancer patients are on treatments for the rest of their lives, however long that is. So the treatments they use have to be tolerable.”

And while some advocates are anxious to make new drugs available as soon as possible, Mayer believes there are dangers in approving them too early. She voices concern about “accelerated approval,” which allows some drugs to be sold before a controlled study has proven them more effective than current treatments. Mayer cites the case of a lung-cancer drug that in small studies had been shown to be effective in 10 percent of patients. It received accelerated approval partly because some patients testified that it helped them dramatically after other treatments had failed. But scientists still didn’t know why the drug worked in those patients and not in others. So how would doctors know who to prescribe it for? “The drug didn’t work in ninety percent of patients,” Mayer says. “My feeling was, how could they have approved a drug without finding out which patients it had worked with?

“If the regulations are relaxed to the extent that we approve drugs that don’t work in ninety percent or more of patients, then we’re opening the door for pharmaceutical companies to continue to market much more broadly than they should,” Mayer says.

The advocacy movement has inspired new research directions, Millikan says. For instance, in 1992 the National Cancer Institute created the Specialized Programs in Research Excellence (SPOREs), which unite basic researchers and clinicians and help move discoveries from the lab to the clinic. “A lot of the rationale for starting the SPORE was to do innovative, translational research in breast cancer, and in turn this was due in large part to the momentum from the breast-cancer advocacy movement,” Millikan says. SPOREs that study many types of cancer are funded around the country, including breast-cancer SPOREs at Carolina and at Duke.

Millikan says that though he has studied mostly genetics, his work with research participants and breast-cancer advocates “constantly reminds me of what else is out there to study.”

Parker, for example, played a role in the discussions that led to Millikan and colleagues asking women what they thought caused breast cancer, as part of the Carolina Breast Cancer Study (a long-term look at four thousand North Carolina women with and without the disease).

The women suggested some possible risk factors that the scientists had never considered, such as physical injury, stress, and bereavement. When Millikan’s team began analyzing its data for these factors, they found no association between cancer and physical injury to the breast. But the other two ideas “turned out to be very interesting,” he says. “Profound emotional loss and loss of health-care due to unemployment were associated with breast cancer being diagnosed at a later stage.” A later diagnosis means treatment may not be as successful.

That result points to environmental exposures that “no one wants to talk about,” Millikan says. “Poverty, social isolation, or racism could have profound effects on cancer rates,” he says. Low-income areas might be exposed to higher levels of pollution, for instance, or physical abuse might lead to stress that could affect the immune system. “It’s very hard to study these exposures,” Millikan says. “But having ‘no evidence of an effect’ because we never studied something is not the same as ‘evidence of no effect.’”

In the paper resulting from that survey, which was published in the journal Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis in 2002, Parker and another patient advocate were listed as coauthors alongside the scientists.

Survivors of other cancers are beginning to take a cue from breast-cancer advocates. According to the National Cancer Institute, advocates play some role in thirty of the fifty-six cancer research programs funded under SPORE, including programs in prostate cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, and lung cancer. At the prostate-cancer SPORE at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in the state of Washington, for example, advocates serve on committees that review plans for clinical trials. And they may soon become involved in improving recruitment of participants, says Suzanne Hall, research coordinator.

Meanwhile, breast-cancer advocates such as Parker maintain their constant presence. Today, Parker serves on the executive committee of a breast-cancer research program at Duke and is patient-advocacy chair for a national organization that designs and conducts clinical trials.

Millikan says that advocates remind researchers of the urgency of their work. “When a patient advocate is at a meeting, the tone of the room changes,” he says. “It reminds us that there’s a lot more at stake than just our careers.”