One early afternoon in February of 2006, Pat Thompson was on a train, heading to Virginia.

She was going to see Jacqueline Branson Smith, who wanted to show her some of her mother-in-law’s artwork. Thompson wasn’t sure what she’d find, but when she got there, “everything was stored under the beds, in closets,” she says.

So on tiptoes and hands-and-knees, she drew out canvas after canvas, portfolios marked “Do Not Destroy.”

And the work was good.

Disappearing act

All artists have to struggle against anonymity, but women have had a harder time of it, says Thompson, UNC’s art librarian. Even beyond historical sexism, women have come up against plenty of obstacles in gaining admission to the boys’ club of “great” artists. Until the late nineteenth century, most women weren’t even allowed the same kinds of art instruction as men — including access to nude models and figure-drawing classes. Critics scoffed at the feminine attempt at creativity, Thompson says, and countless women artists have vanished from sight — if they were even on the radar in the first place.

“When I was in school, Janson” — the staple survey art history text — “didn’t even have women artists,” Thompson says. “Frida Kahlo, Angelica Kauffmann, Lavinia Fontana, the big names — they weren’t in the surveys.” And while art history texts have gotten better over the last thirty years, she says, “it’s like being part of any other minority in your field. It takes a long time.”

Almost every day of her career, Branson painted in her studio, Thompson says. From the 1910s, when Branson was a young woman, until she could no longer draw a straight line, she sat down in front of her easel at 8:30 every morning, five days a week. But when she died in 1976, she left her work with her family, and her name fell off the map — until the year 2000, that is. That’s when Thompson published the list of artists included in the library’s North Carolina Women Artists file. And that’s how Smith found her mother-in-law’s name in the collection.

The file consisted of newspaper clippings and postcard-size exhibition announcements for North Carolina women artists. For some women, the scraps of paper were the only evidence that remained of their art and careers.

Rhythm and movement

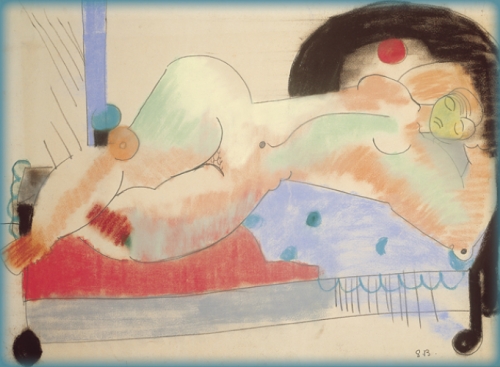

Edith Branson was one of a growing number of female Modernist painters at a time when that meant a precarious break from other, more traditional types of art. And although Branson knew how to draw and paint accurately, Thompson says, she moved toward abstract art as a way to represent things she saw in real life. “Her work was abstract, but abstracted from natural forms,” Thompson says.

For most of her career, Branson lived and worked in New York City. Although she attended some classes at the Art Student League and Teachers College, she never went to a formal art school. Instead she sat for hours in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, copying works, practicing. “She considered that her art school,” Thompson says.

But Branson’s work is different from that of her contemporaries. “She was trying to push the envelope and develop her own style in the context of the Modernist movements of the time, movement away from representation,” Thompson says.

During her “classes” in the Met, Branson studied the classical sculpture and decided that instead of copying rigid characters onto her canvas, she wanted them to move.

Few of her paintings are titled, but one group, which Thompson and Smith have begun to call “Nudes with Ribbons,” are most likely based on those sculptures. “She was trying to capture rhythm and movement,” Thompson says. “And I think she was successful.” Branson experimented with creating visual music and synchromy, which is a style that consists solely of color and shapes.

“She was very rebellious, and a revolutionary in her art,” her daughter-in-law says. “But she was also a very gentle person, very modest and sensitive.”

Trail of crumbs

Branson’s husband — then dean of Columbia’s law school — was well-to-do, and they managed to be comfortable even through the Great Depression. Branson knew that unlike many of her fellow artists, she didn’t have to rely on selling her paintings to make a living. She paid most of the rent for the studio she shared with several other artists, and decided that, while she’d like people to see her work, she wouldn’t try to sell it.

“She didn’t want to compete with her fellow painters, who needed the money,” Smith says.

Her lack of self-promotion may be why no one knows her name today, Thompson says. Branson ran with a circle of New York avant-garde artists over the course of two decades. Many of the other women artists in that scene eventually abandoned their work for homes back in the Midwest and more profitable types of painting. “From then on, they did still lifes and other representational work,” Thompson says. “Branson never changed to a marketable style.”

Branson exhibited her work whenever she had the chance. In a rare interview from 1961, she recalls, “Those were exciting days. We were all outcasts, more or less. Alfred Stieglitz, owner of Gallery 291 and just returned from Europe, was the only person interested in showing our work. He became Georgia O’Keeffe’s husband, you know.”

Branson moved with her family to North Carolina in the 1960s. When she grew too old to paint precisely, she turned to crafts such as weaving, costume design, and painted furniture.

And by the 1970s, as her health was failing, she began to wonder what would happen to her life’s work when she was gone. As she got sicker and sicker, she begged her son and Smith, his wife, “Please take care of my paintings.”

“Sometimes when you get old, you have regrets,” Smith says. “Edith did not talk too much about her work. But I knew it was extremely serious and important to her.”

For decades after Branson’s death, Smith and her husband continued to write letters to museums and archives, trying to find someone who would take the paintings, care for them, and keep Branson’s legacy alive.

Branson submerged

When Smith found Thompson, the two continued the research Smith began years ago. Branson didn’t leave much in the way of diaries, letters, or even notes about her art, and so they’ve been working together to connect the pieces of her life and career.

“Branson had talent,” Thompson says. “And she was devoted to her art. She wasn’t after fame and fortune — she just loved to create art, even until her old age.”

And now that she’s gone, Thompson says, you won’t find much about her or her work in any art history texts.

Yet.

“There are a number of good biographical dictionaries of women artists, and more and more are being produced,” she says. But the few entries that exist for Branson are incomplete and, in some cases, incorrect. Thompson plans to change that.

“I’m not about to throw my hands up any time soon,” she says. “I didn’t start out trying to resurrect forgotten women artists, but it seems to be my mission.”

Pat Thompson is the librarian of UNC’s Joseph Curtis Sloane Art Library. Her research on Edith Branson’s life and work was supported in part by a Wildacres residency. In the coming year, she will post her findings, as well as an online Branson archive, to the library’s web site at www.lib.unc.edu/art/.