Are you liberal? Or conservative?

Are you sure?

Political scientist James Stimson pored over thousands of public opinion polls — decades’ worth — and discovered that each year about 22 percent of Americans call themselves conservative, even though they take a liberal view on nearly every domestic policy issue, and some major social ones. These voters — average Main Street Americans — believe that the government should spend more money on education, environmental protection, and health-care reform — each one a liberal view of governance. In 2004, that meant these citizens sided with nearly 80 percent of the American public. In fact, the majority of voters support most of the liberal views, even though Americans label themselves conservative by a two-to-one margin.

You might think that these voters actually consider themselves social conservatives who cherish hard work, strong family life, and patriotism. All of that’s true, but most of them also believe in gay rights and a woman’s right to choose, among other socially liberal views.

They’re economic liberals and social liberals, but they peg themselves as conservative.

“These folks are really conflicted,” Stimson says.

How come?

The power of language

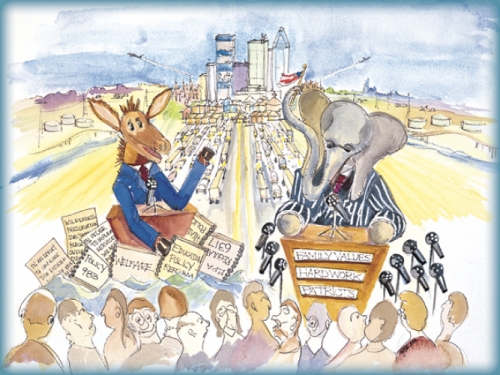

Stimson says that Americans’ preference for the word conservative over liberal dates back to FDR and the New Deal, when pollsters began asking people about their political leanings. Knowing this, conservative politicians have linked conservatism to cherished ideals — which Stimson calls political symbols — such as patriotism, hard work, and family values. Voters relate to these things and associate themselves with politicians who do, too.

Meanwhile, an opposing force is at work.

Stimson says that the media, simply by covering the issues, constantly prod the government to do more to help people. This influences voters to believe that the government should do more. The media, Stimson says, essentially promote changing the status quo — a liberal activist view. For instance, Stimson says, “Almost no one says that education is good enough, the government should do less. No one thinks that health care is good enough, the government should do less; the environment is fine, the government should do less.”

Because of this paradox, Stimson says, elections often come down to which candidate best controls the campaign conversation. If it’s a largely slogan-like conversation about ideals, Republicans generally fare better. If it’s a domestic policy discussion, Democrats generally have the upper hand.

Foreign policy issues present more complications because the politicians switch perspectives too often, he says. Yet rhetoric comes up big in these debates too. The Iraq debate, Stimson says, was all about ideals — patriotism, steadfastness, and decisiveness.

All of this may sound simplistic, Stimson says, but the conflicted swing voters at the heart of his research don’t really care about politics; they’re less involved and less knowledgeable than truly conservative or liberal voters. “Yet these folks vote in substantial numbers.”

And politicians know that.

Code Red

Family values is one of the most famous examples of politicians appropriating a popular social ideal. Republican leadership introduced the catch phrase at their 1992 national convention. But that event, Stimson says, was filled with anti-gay rights rhetoric, not speeches about education, the divorce rate, or raising a family based on ethics and virtues.

“It’s well known in the political science field that family values is code for anti-gay rights,” Stimson says. “They have focus groups for all of this.”

Again, the code is aimed at the true-blue conservative Republicans, not the moderate Americans, who are by far the majority of the electorate and who cherish their families, Stimson says. But many of them believe in gay rights, thus the need for code. These voters don’t hear anti-gay rhetoric when a politician talks about family values, Stimson says. They hear Lake Wobegon.

Stimson says that Democratic candidates should turn rhetoric into a policy discussion. For instance, a candidate could respond to family values rhetoric by saying that he too believes in family values, and that a fundamental value is education. And then have a good plan for education reform.

Would that work?

Maybe, maybe not.

Out of touch electorate

Stimson says that a huge portion of the electorate simply doesn’t pay close attention to policy issues, which may be why rhetorical symbols work so well and why so many Democratic politicians are now using phrases such as honest government and real security.

“Clearly the level of public knowledge is not remotely what democratic theory expects it to be,” Stimson says. “A very large number of people are going to polls without knowing the names of either candidate and are still pulling the lever.”

Stimson found that voters often don’t know where candidates stand on key issues. He used polling data from 2000 to isolate a group of religious conservatives who said abortion was their top issue. But just two weeks before the presidential election, only 44 percent of these voters knew that Al Gore was pro-choice. Fifty-six percent either got the question wrong or didn’t answer it. “And these are religious conservative voters,” Stimson says. “We always overemphasize how much people care.”

Sadly, these results suggest that Stimson’s research is more about indicting a huge swath of the American electorate, not a particular political strategy. And this doesn’t include the majority of Americans — the ones who don’t even vote.

“We get the sense from the media that people are all worked up out there, and that’s just not true,” Stimson says. “The electorate is pretty much tuned out.”

James Stimson is Raymond Dawson Professor of Political Science in the College of Arts and Sciences. He received a Guggenheim fellowship for his research entitled The Liberalism of Professed Conservatism in America and is currently writing a book on his findings.