Tuesday, 8:30 a.m. Brenda Johnson walks the aisles of Raleigh’s food-bank warehouse, peering up at boxes stacked twenty feet high. She searches for rice, canned goods, produce — any staple she can give to those in need in her hometown of Dunn, North Carolina. She tells her volunteers what she wants. They jot down a list of items and hand it to the food-bank attendant, who then forklifts 6,600 pounds of food into Johnson’s big, yellow truck.

Back at the church where she ministers, Johnson helps ten congregants pack grocery bags full of food and then helps deliver the bags to hundreds of people. She does this every week, just like thousands of other North Carolinians who lead soup kitchens, pantries, senior centers, day cares, and shelters — independent nonprofits that operate on small budgets and get little or no government support. No umbrella organization oversees their work. Yet hundreds of thousands of people across the state depend on people like Johnson for the most basic necessity of life.

In fact, according to the national nonprofit Feeding America, 12.6 percent of all North Carolinians experience something called food insecurity, which means that they don’t have reliable access to food.

“That’s an incredible number,” says Maureen Berner, a professor in UNC’s School of Government who researches poverty and hunger trends. That’s more than a million people who might know how they’ll put food on the table tonight or tomorrow but not at the end of the week or month.

Every Tuesday morning Brenda Johnson travels an hour from Dunn, North Carolina, to the Food Bank of Central and Eastern North Carolina in Raleigh to buy food. Her nonprofit pantry, Recruiters for Christ, is open every Wednesday. Food bank perishable-food assistant Michael Night forklifts a palette of food from the warehouse floor onto Johnson’s truck. Johnson’s church also donates money to the food bank to make sure her congregation helps others in need who do not live in Dunn.

When Berner and Sharon Paynter first teamed up to study food insecurity, they had two main questions: Who are the people who seek food from pantries? And for how long do they need help? But the answers to these questions raised new, larger ones. If hundreds of thousands of people depend on volunteers like Johnson for food, is the government abandoning its traditional responsibility of helping those in need through welfare programs such as food stamps? And is that a bad thing?

For several decades, thousands of dedicated volunteers have operated North Carolina’s food pantries and soup kitchens as part of church charities or independent nonprofits, Berner says. They get their food from different sources, but most of it comes from one of six food banks, also nonprofit. These food banks get nearly all of their products from supermarket chains, food companies, individual donors, and local farms. The state and federal government provide some funding.

There are nearly five hundred pantries in the thirty-four counties served by the Food Bank of Central and Eastern North Carolina. Most are run by faith-based groups of volunteers. Berner says she’s amazed at the amount of work the volunteers put in, but if donations to food banks and pantries decrease, the volunteers will have to work that much harder to find alternate means to feed the poor. And if they can’t, then food insecurity could turn into hunger and malnutrition.

“I question the capacity of these nonprofit pantries to keep this up,” Berner says. What happens when a volunteer such as Brenda Johnson, who has devoted her entire life to aiding the poor, can no longer lug bags of groceries around Dunn? “Whenever I ask that kind of question someone at the church always tells me that another person will fill her shoes. They say that for hundreds of years churches have been doing this kind of work; they’re closest to the people and care the most.”

At Recruiters for Christ, a food pantry in Dunn, Nora Hernandez of Newton Grove and her daughter Yurdia Lopez wait in line with about thirty others to receive food on a Wednesday morning during the summer of 2009.

But if nonprofits start struggling, or if demand skyrockets, will the government sustain them? Right now, state and federal governments provide small amounts of funding for food banks. More and more people are relying on pantries stocked by those banks, and most of the pantries are getting larger. In the 1980s, Johnson’s pantry was housed in a backyard shed. Today it’s in a 2,100-square-foot building. And Johnson plans to grow her operation even more.

As demand increased, the Second Harvest Food Bank in Winston-Salem watched its food supply plummet from 810,000 pounds of food on June 30, 2009, to 500 pounds three weeks later. Once news of the crisis broke, individuals and supermarkets came to the rescue with donations and food drives. Berner says that it’s easy to think that the current recession and high unemployment caused this crisis. But she points out that increased demand is a symptom of deeper problems, one of which dates back fourteen years — to August 22, 1996.

When President Bill Clinton signed welfare-reform legislation into law, his goal was to make sure that people couldn’t abuse the system by staying on welfare their entire lives. He wanted people to get jobs, so he made welfare time-bound.

Four years later, when grad student Kelley O’Brien interned at the Food Bank of Central and Eastern North Carolina in Raleigh, she noticed that more and more people were coming through the doors. She and Berner decided to study how pantries were using the food bank before and after the 1996 Welfare Reform Act. They found that as the government’s role in providing food stamps decreased, pantries started providing much more food to their clients. In fact, people sought help from food pantries instead of the government even when they did qualify for food stamps.

“Welfare reform wasn’t food-stamp reform,” Berner points out. “But a lot of people were scared away from the program. They thought they couldn’t get food stamps anymore or they thought they wouldn’t qualify.”

Between 1995 and 2000, the 193 food pantries that Berner studied bought about 100,000 more pounds of food from food banks than they had in the five years before welfare reform. Then, in 2000, use of food stamps began to climb again. Welfare laws hadn’t changed, but other things had: there was more outreach into poorer communities, and people were allowed to stay on food stamps longer. Also, Berner says, the stigma associated with using food stamps waned. Meanwhile, more and more people kept seeking help from pantries.

Joyce Edwards at her home in Ashton Spring Apartments, an independent living center for seniors in Ayden. She goes to the Ayden Christian Care Center once a month for food. Here, she laughs during a conversation with a personal-care assistant who helps Edwards complete daily tasks.

In 2003, Berner’s father grew ill and she moved to Iowa to be closer to him. She taught at the University of Northern Iowa for two years and continued her research at the largest food pantry in the northeastern part of the state. Berner found that people who had jobs did not get off food assistance faster. “In fact, it was slightly more likely that people needed long-term assistance from a food pantry if they did work,” she says. “It seems counterintuitive, I know.”

But there’s logic to it. When people are working, Berner says, they have a lot of expenses, such as car payments and day care. They pay for these expenses with the idea that income will allow them to make ends meet or eventually get a better-paying job. “But the people going to food pantries often stay stuck in low-wage jobs,” Berner says. “They’re stuck in that low standard of living.” And if they stay at those low-paying jobs long enough, eventually the rising costs of living will catch up with them and they’ll have to sacrifice something — buying groceries, for instance.

In 2005, Berner returned to UNC and has been studying poverty and hunger trends here ever since. She teamed with Paynter at East Carolina University to analyze several hundred random client files from forty pantries in central North Carolina. Here’s what they found:

- Most clients returned to pantries consistently for more than one year.

- The average client returned to pantries for five consecutive years.

- 24 percent of clients were married with no children.

- 15 percent were elderly and single.

- 42 percent were married with kids.

- Many pantry clients, but not a majority, received food stamps.

- In 2007 the median income of clients was 29 percent lower than that of other North Carolinians.

- Only 7.8 percent of clients were living below the federal poverty line.

- Berner and Paynter also found that most pantries are helping more people.

“At one pantry, our grad student Emily Anderson pulled out a drawer full of client files for 2008,” Berner says. “Right next to it was another cabinet that was also full, and those files were from just the first two months of 2009.”

From 1997 to 2005, food-pantry demand increased steadily, Berner says. In 2009 demand on the Second Harvest food bank in Winston-Salem rose 76 percent; throughout the rest of North Carolina, demand on food banks increased 30 to 70 percent.

These numbers made Berner and Paynter wonder about the supply side of the equation, so they started studying where pantry operators such as Brenda Johnson get their food. In conversations with food bank and pantry operators, they learned that pantries used to be stocked with about 80 percent canned goods or prepackaged, processed food. “The other 20 percent was local farm produce,” Berner says. Today food banks and pantries probably get more produce than they do prepackaged food.

The trend toward produce is a precarious one. A lot of crops still rot in the fields. And even if every field were picked clean, many shelters, soup kitchens, and pantries would still lack the capacity to store the vegetables; they’d need refrigerators and freezers. Berner and Paynter say that many pantries do have refrigerators, but not enough to deal with the kinds and amounts of food that pantries now receive.

Paynter used to work at a nonprofit that operated one such pantry. One day, two hunters drove up and asked her whether she wanted a deer that they had killed. Paynter didn’t know what to say. She lacked the freezer space to keep the meat and a place for the hunters to butcher the carcass. She wondered about health regulations and if clients would even want venison. But protein-rich foods — whether canned tuna, peanut butter, or red meat — are like gold to pantry operators. The hunters wound up butchering the deer in the parking lot, and they also cleaned the cuts of meat. Paynter then gave the venison to some clients, who were grateful.

For Paynter and Berner, the scene highlighted a growing problem: the hardest donations to deal with are the foods that are freshest and most healthful.

This is one reason why the food bank in Raleigh used a portion of its 2009 financial donations to buy ninety freezers and refrigerators for member agencies. Still, there are thousands of charities that are underfunded and undersupplied. Some operate out of tobacco barns, and many more out of church basements. They do what they can — often quite a lot — but state-wide it’s not nearly enough.

Berner also points out that while eating vegetables is much more healthful, preparing them isn’t always easy. “You have to know what to do with ten pounds of sweet potatoes, for instance,” she says.

John Freeman unpacks bags of groceries from the Recruiters for Christ pantry in October 2009 as his wife Eunice sneaks a cookie. John is retired and the couple’s only source of income is Social Security. They live in a two-bedroom ranch house near Dunn.

Berner and Paynter have presented their findings at conferences across the country, sharing statistics and stories. They show that food insecurity is a better indicator of poverty than traditional barometers such as annual incomes or the unemployment rate, which don’t capture whether people can maintain their households or put food on the table.

“The people who go to pantries are not homeless, and most have jobs,” Berner says. “They are the working poor.”

Berner and Paynter had a hard time connecting the statistics with real people’s stories until they met Donn Young. A photojournalist from Louisiana, he’d moved to Chapel Hill after documenting the destruction of Hurricane Katrina as the official photographer for the Port of New Orleans. Young wants to help create image libraries for university researchers, especially those working on human rights issues. He contacted Heather Hunt, assistant director of UNC’s poverty center, and she introduced him to Berner and Paynter. Young immediately saw the story lines in Berner’s research.

“I wanted to document the entire distribution network,” Young says. “This thread that starts with the farms and grocery stores, connects with the food banks and the pantry workers, and then finally with the people who need food. Maureen and Sharon saw the value in this right away.”

So did the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, which in May 2010 will feature Berner, Paynter, and Young’s work in photo displays and a presentation for the North Carolina General Assembly. The office will also house the photo essays and research at its Raleigh library.

“I was thrilled that I had five thousand lines of data, but I had trouble visualizing it like a story the way Donn could,” Berner says. “He’s really spurred me to think beyond the data sets. I tell Donn that the food pantries are giving people vegetables more now than ever before, and then he wonders where this produce comes from. So he goes to the farms to document the farmers’ lives and the volunteers gleaning the fields. He tells their stories. And then I can go back and research what happens at these farms, how much of their crops go to pantries. This is engaged research. It’s about people.”

At McAdams Farm in Efland, Young met Harry Jones, who volunteers with the Orange Congregations in Mission pantry. “Harry’s had eight brain surgeries,” Young says. “He’s got leukemia. And yet he gets up every morning, fills up his truck with gas at his own expense, and takes whatever’s left over in the fields to food pantries.”

“This is the stuff my research can’t capture,” Berner says. “This man’s dedication is typical of the whole network of pantries.”

Most of the people who run pantries are white, older, and part of a Christian charity, Berner says. For many of them, feeding the poor is their calling. Brenda Johnson was twenty-eight when she and her aunt started a mission called Recruiters for Christ. With a large, cast-iron washtub in hand, they’d pick crops that were about to rot in neighborhood gardens and on local farms. They’d gather fallen fruit from under trees. Then they’d wash and package the crops and take them to neighbors in need.

“We had this car with a door that would fly open when we’d turn a corner,” Johnson laughs. “There was a hole in the floor and the tires were bald. But we never had a problem. It only got a flat when my husband drove it.”

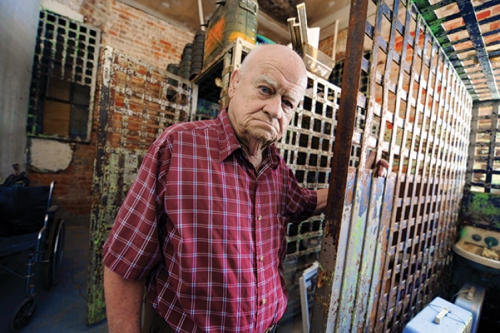

Cliff Stang, the past director of the Ayden Christian Care Center, stands in an old jailhouse that has served as the center’s food pantry for many years. Stang still volunteers at the pantry every week.

Thirty years later, Johnson’s mission now includes a nondenominational church with about sixty members. Many of them help her buy tons of food from the food bank in Raleigh. The church also donates two hundred dollars each month to the food bank. “This way, we not only help people in Dunn but help others who need it, too,” Johnson says. “That’s a great blessing. To be able to do this work is a blessing.”

Berner and Paynter don’t doubt that others would step up if such a dedicated woman were no longer able make her rounds. But Berner says that charities, no matter how well-organized, have never been able to keep up with food demand. Hundreds of pantries have popped up in the past two decades, while existing pantries have gotten larger. Such increases have merely created more access points for pent-up demand, Berner says. For example, after Hurricane Floyd flooded eastern North Carolina in 1999, the Raleigh food bank established temporary food-assistance agencies down east.

“Those agencies never closed,” Berner says. “Demand there has never been close to being met.”

Berner says it’s tempting for the government to try to solve the deep-rooted problems that beset people who seek help with food. But a simpler and more practical approach, she says, might involve attention to supply-side issues, such as providing refrigerators, freezers, and other resources to food banks and pantries.

“If we really want to address hunger,” she says, “maybe we should focus on the barriers that limit pantries and other food providers, rather than on the seemingly intractable problems of individuals.”

Maureen Berner is a professor in the School of Government at UNC and Sharon Paynter is an assistant professor of political science at East Carolina University. Donn Young is an award-winning photojournalist whose work has appeared in nine books and national publications such as Time, Newsweek, The Washington Post, The New York Times, and USA Today. Brenda Johnson is the minister of Recruiters for Christ, a nondenominational church and mission in Dunn, North Carolina. Kelley O’Brien is now the director of the North Carolina Civic Education Consortium in UNC’s School of Government. The School of Law’s Center on Poverty, Work and Opportunity gave Berner a ten-thousand dollar grant to hire grad student Emily Anderson to collect data from pantries in central and eastern North Carolina.