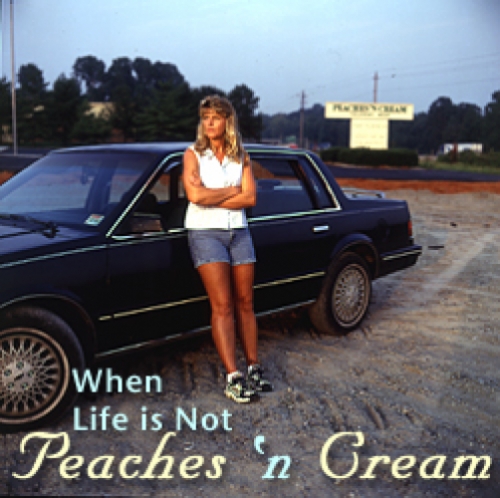

When Carol Crabtree cut cloth for children’s dresses, she thought of the little girls who would wear them. It was more than a job. The women who worked with her at the Peaches ‘N Cream plant in Mebane were as close as family. When her house burned down and she lost everything, they took care of her.

And the company itself—the family-owned May Apparel Group—treated its employees with respect, as though they were partners, Crabtree says. Many times, to stay on schedule, Crabtree and her coworkers voluntarily worked late into the night and on weekends, just to make sure the clothing samples were ready on time.

But in May, after 18 years with the company, Crabtree worked her last shift at Peaches ‘N Cream. Her division had closed. While the company would retain a small base in North Carolina, the manufacturing was moving to Mexico. The Mebane plant—where the tools had been scissors and yardsticks, not the computer-driven machines of modern apparel factories—was no longer able to compete. The bad news came last fall.

“We cried from October to May,” Crabtree says.

Across North Carolina, factories in the state’s traditional industries are closing their doors, and many thousands of workers like Carol Crabtree are losing their jobs.

“A lot of the state’s mass-production, mass-market jobs are going to Asia or Mexico,” says Mike Luger, professor of public policy analysis and director of Carolina’s Office of Economic Development. “Some things can still be produced here, but for workers, the skills required are much different. Emerging industries are using computer-aided equipment.”

Some of the best manufacturing jobs are in industries that aren’t yet synonymous with North Carolina—metalworking, plastics, and telecommunications, for instance. Even traditional money-makers, such as agriculture, are evolving high-tech systems for producing and distributing their products.

In each of the new “emerging” industries, the common denominator is technology, Luger says. While there are still some good jobs that don’t involve computers, they are few and far between. For workers over 40—people who didn’t grow up with their fingers on a keyboard—making the jump to computers can be daunting. As Crabtree puts it: “It’s hard to go from a job where you’re doing good, physical work to one where you sit in front of a screen punching keys every day.”

Statewide in North Carolina, many thousands of workers find themselves facing the same hard choices.

“A lot of the workers being displaced have invested many years in their careers,” Luger says. “Getting them back into training is difficult. The older people are, the harder it becomes to change hats and learn a new set of skills. Many have children who are in high school, with friends and activities. These workers usually don’t feel free to stop working and go back to school, even if they know that’s their only hope for finding a job with a future. It’s a risk, and the system doesn’t compensate them for taking that risk. So a lot of workers are forced to take lower-paying jobs just to pay the bills.”

Last October, Luger’s office issued a report that has begun to help the state rethink its policy toward displaced workers. “Worker Dislocation in North Carolina: Anatomy of the Problem and Analysis of the Policy Approaches” details how the state’s unemployment insurance system, worker training, and community colleges have not kept pace with changes in the workforce. Written by Luger with Lucy Gorham, a policy analyst, and with Ph.D. student Brian Kropp, the report proposes fundamental reforms.

In response, the governor’s office is expected to propose legislation to address several of the report’s recommendations, Luger says. And the state’s community-college system has asked Luger to help it restructure job training programs so that they are more relevant and timely for displaced workers.

Luger’s report recommended, for instance, that programs for retraining displaced workers become more flexible so that people could begin training soon after losing their jobs. Carol Crabtree, who lost her job in May, will have to wait until the fall semester to enroll in the community-college courses she would need to learn a new trade. By her first week of classes, she will already have expended almost half of her 26 weeks of eligibility for unemployment insurance. Also, her unemployment benefits are so low—only half her former wage—that she can’t afford to go to school. She has considered work in a warehouse, but the job would pay less than she needs.

According to Luger’s report, fewer than half of displaced workers in the state’s traditional industries find work in the same sector that employed them previously. For Carol Crabtree and other apparel workers, the odds are even worse—only about 40 percent find jobs in the same sector as the jobs they lost. For the first year or two, displaced workers average making about three-fourths the pay of their previous jobs, Luger has found.

Luger says that Crabtree’s case is typical. “A lot of apparel workers are being employed in call centers—telemarketing and catalogue order,” he says. “These are essentially minimum-wage jobs. That’s what you get when you don’t put the time and effort into reskilling these workers.”

This kind of displacement can have a traumatic effect, not only on the worker and her family, but on the community as well. Unfortunately, neither public nor private institutions offer much help.

“The programs set up to retrain workers tend to be based around major plant closings,” Luger says. “They are not serving very many workers, especially those from the smaller plants and businesses scattered all over the state.”

When he began the research, Luger had expected to find that community-based organizations such as churches and civic groups might be helping displaced workers adjust. But it wasn’t the case, he says. “Many workers are on their own,” Luger says. “And they are discouraged.”

Bringing such issues into the spotlight hasn’t been easy, Luger says. The state is enjoying a period of robust prosperity, and the statewide unemployment rate remains low (about 3.3 percent at this writing). But not everyone has a share of the boom. In rural areas, disconnected from thriving urban growth, many once-vigorous farming communities and blighted factory towns struggle with double-digit unemployment.

Just as troubling, Luger says, is the fact that the booming economy disguises a number of deep-seated problems in the workforce, temporarily absorbing displaced workers into low-paying jobs that are likely to vanish when the inevitable economic downturn begins. In the next recession, Luger says, the job options for displaced workers will decline sharply. Many of the workers who have not learned new skills will make their way onto the welfare rolls. In rural communities, tax revenues will fall, and towns will quickly spiral downward.

“In the long run, what will cost more, spending the money now to reskill these workers, or paying the welfare costs later?” Luger asks. “Our analysis tells us that it would be wise to invest now to extend unemployment benefits and to improve opportunities so that workers can learn the skills they need.”

Luger says the state cannot afford to lose the strong social fabric and the solid work ethic of its rural communities.

“Some of these communities are real gems,” he says. “They are full of good, hard-working people who just need to join the twenty-first century. The towns may be stagnant, but the human potential is enormous.”

Luger’s office works with such communities to identify opportunities for jobs and economic growth. He thinks that connecting small towns to the information superhighway will help people preserve their rural lifestyles by enabling them to telecommute to Raleigh or Charlotte without joining the rat race and rush-hour traffic.

Another benefit of better training, Luger says, is that the state would develop the skilled workforce it needs to compete for the most desirable industries. Luger’s office is working with the community-college system to develop “industry cluster resource centers” that would develop, region by region, labor forces relevant to a range of strategically important industries. The goal is to help bring displaced and underemployed workers into the economic mainstream.

But a skilled workforce isn’t the only necessary ingredient for recession-resistant prosperity, Luger says. In the new economy, the big winners will be those who also invest wisely in science and technology. A commitment to this sort of investment once set North Carolina apart from other states, Luger says. Not any longer.

“We are losing our advantage,” he says. “Five years ago, we were one of the top states in investment in science and technology. Now we’re in the middle of the pack. Other states—Virginia, Pennsylvania, Georgia, and South Carolina, for example—have invested a lot more than we have in science and technology. The goose that laid the golden egg here has been our farsighted thinking in terms of the universities, the Research Triangle Park, the Biotechnology Center, and those kinds of things. We’re still in pretty good shape, but it’s getting a lot more difficult to compete.”

Despite the erosion of investment, Luger is optimistic about the state’s ability to regain a strong economic momentum, largely because officials are once again turning to the university for help.

“For a long time, Carolina has had the ability to blend the social sciences with the hard sciences to serve the state’s interests,” Luger says. “When you’re facing a period of dramatic social and economic change, science and technology are important, but you also have to understand people. That’s our great strength.”

For Carol Crabtree and her friends from Peaches ‘N Cream, life won’t wait on the slow evolution of public policy. She has bills to pay and a growing boy to feed. So Crabtree is looking for work. She thinks she might enjoy landscaping—working outside with plants—and she might eventually go back to school with that in mind.

But even though she is still young at 42, she knows it will be difficult to reinvent her life after 18 years of secure, rewarding employment. She still grieves the loss of the job she loved. And yes, she is worried, she says. But she knows she has the strength and the will to work hard and do a good job. She has told her son, who starts high school this year, that they will be okay.

“He knows that we’ll have less money,” she says. “But we’ll get by.”

Neil Caudle was the editor of Endeavors for fifteen years.