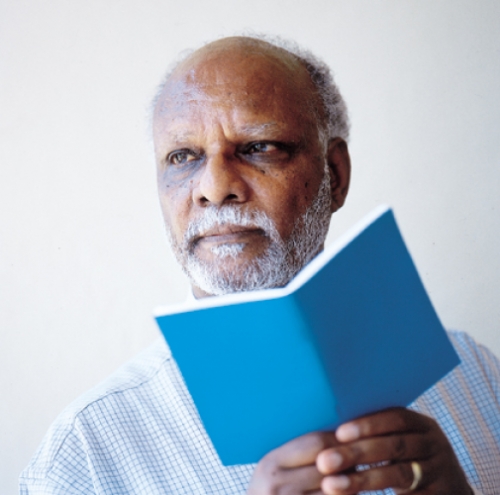

Out of his briefcase Bereket Habte Selassie, professor of African and Afro-American studies, pulls a blue, pocket-sized booklet. Selassie carries it with him always. It is the constitution of Eritrea, Africa, and he wrote it.

To understand, you have to go back more than 40 years. In the late 50s and early 60s, Eritrea and Ethiopia were still joined in “a very lopsided federation in which Eritrea had some autonomy, but the Ethiopian government had sovereignty over Eritrea,” Selassie says. At that time Selassie was serving the federation as a judge of the Supreme Court and then as attorney general. Though he was a public official, Selassie had what he calls an “uneasy” relationship with the government, disagreeing over human rights and other issues. “When the emperor decided to abolish the federation arbitrarily, illegally—I resigned.” Selassie says.

For a couple years Selassie worked as an attorney with the World Bank in Washington, D.C. Then he joined the Eritrean freedom fighters. He served as a diplomat and represented them at the United Nations.

“You are talking about a person who had known public office as a judge, a lawyer, and then takes up arms against the government,” Selassie says. “A lawman turned outlaw, so to speak.”

The war for independence from Ethiopia lasted 30 years. Meanwhile, in 1975, a civil war broke out in Eritrea. Selassie mediated that conflict and helped bring about a cease-fire. He eventually decided to join one side because, he says, it had concrete aims of social justice and equality, rather than simply control of the government. “You can’t be neutral when a nation’s life is involved,” he says.

In 1991, Eritrea finally won its independence. The country needed a fresh start—and a new constitution. For that, leaders turned to Selassie, who by then was living in the United States. He agreed to serve as the principal draftsman of the constitution and to chair the 10-member drafting committee as well as the 50-member constitutional commission.

First, Selassie made sure to consult the Eritrean public. “From the beginning I made it quite clear to the members of my commission that we were servants of the people and had to consult with them as the stakeholders,” he says. The commission prepared educational documents on issues such as separation of power, the rights of women, and the contents of a constitution and had them translated into four of Eritrea’s most common languages (there are nine languages and four ethnic groups in the country). After documents were broadcast over the radio and distributed in print, citizens attended public debates.

Selassie and each commission member traveled to different parts of Eritrea to begin the debates, which were held in schools, town halls, and even outdoors. “There are some nomadic communities, so we’d move with them, share a meal, and talk,” Selassie says. Though many citizens are uneducated, he says, after receiving some information they would debate enthusiastically. “If you invite the villagers for three or four hours, they like it so much that they debate throughout the day and some even overnight.”

T

he citizens also shared their own form of knowledge. “I learned that there is such a thing as folk wisdom, the distilled wisdom of centuries,” Selassie says. “Village elders who have not taken classes in law can engage you for hours using beautiful language—rhyming couplets that they know from childhood.”

A crucial debate was whether the country would be governed by an elected president, as in the United States, or if there would be a parliamentary government similar to Great Britain’s. The commission decided to try something that no other country ever had—a combination of the two. The public elects a parliament, and then the members of parliament elect a president from among themselves. “Once elected, he becomes an executive president like that of the United States,” Selassie says.

This experimental form of government is an attempt to ease Eritrea’s transition to constitutional democracy, Selassie says. Since Eritrea is evenly divided between Christians and Muslims, “the mechanisms of electing the president should be carefully devised,” he says. If citizens voting for the first time made choices based on those divisions only, “you may not get the best candidate,” Selassie says. The commission also hoped that if a parliament composed of members of multiple political parties elected one president, the election would involve much debate and compromise. “In our view that makes for good politics,” Selassie says.

That brings up another hard-fought issue. Though right now there is only one political party in Eritrea, Selassie insisted that the constitution provide for the people to have the right to organize multiple parties. “That took a fight,” he says. Some members of Eritrea’s government and political party advocated that a single party was needed to unify the country and encourage economic growth.

“That is an illusion,” says Selassie, who studied Africa’s experience with single-party rule for his doctoral dissertation. “Sooner or later the leaders of the single party end up as dictators. They appoint in key places members of their families or friends and use power to accumulate wealth. That leads to crisis and conflict.” Selassie let it be known that if the ruling party didn’t accept the stipulation about multiple parties in the constitution, he would resign from the commission.

When he began to write the constitution, Selassie used proposals from the public debates as well as issue papers from experts and constitutions from other countries. “It went in my own hands through at least three or four drafts,” he says. Then the drafting committee debated each article of the constitution at least twice. Next it was approved by the constitutional commission and the Eritrean parliament before being ratified in 1997 by an elected constituent assembly. At the commission’s suggestion, the government printed pocket-sized copies of the final constitution and distributed them to citizens free of charge.

That document didn’t mark the end of Selassie’s work. Now some members of the ruling party’s inner circle are resisting the multiple-party idea. In Selassie’s office sits a black-and-white photo of several soldiers taken during Eritrea’s civil war. Selassie points out himself and Eritrea’s current president. They were once on the same side. But now Selassie suspects that the president is part of the movement resisting a multiple-party system. “These people had power for too long,” Selassie says. “Once you taste power, you don’t let go.

“During the liberation struggle, we depended on the sense of loyalty to the nation and to principles,” he continues. “We expected there’d be a self-checking mechanism. It’s not true anymore.”

But Selassie is confident that the reform group will establish multiple parties. The Eritrean government is dependent upon support from the many educated and influential Eritreans who live in Europe and the United States. Especially in a crisis, this group of people can make a large difference, Selassie says. “If the diaspora community is in favor of multiple parties and says so, then sooner or later the government has to accept it. And the constitution is on our side.”

But there is still more work to be done. “We are not out of the woods yet. It will take three, four, even five years,” Selassie says. As usual, he is in the middle of the debate. “In my golden years I was looking forward to a nice life of gardening, reading, and reflection,” Selassie laughs. “Nevertheless, it is a blessing to be able to serve. Until the constitution is completely implemented and there are multiple parties functioning and healthy politics established, I will not think of my work as completed.”

Selassie is also serving as a consultant to teams writing or revising the constitutions of Nigeria and Rwanda and has been invited to do the same in Somalia. His book about the making of the Eritrean constitution will be published in 2002 by Red Sea Press (Lawrenceville, N.J.).