The last time he was in Tanzania, Paul Leslie was first a lion then a witch. Or that’s the way some Maasai children saw it.

“We’d gone down to an area in Maasai land where there aren’t many tourists,” Leslie recalls, “so there are a lot of people, particularly children, who have never seen white people up close. My friend Terry McCabe, a cultural anthropologist, and I were there to talk to people about the herding and so on as part of our work. But the young people were afraid of us because they thought we were lions. We looked like lions with this facial hair and hairy arms and pale eyes.”

To reassure the children, Leslie and McCabe gave them cookies and sat with them under a shade tree. After a while, it was time for Leslie to call Chapel Hill on his cell phone. So Leslie strolled away from the shade tree and phoned home, wandering and gesturing as he talked. Five minutes later, when he turned back to the shade tree, “all hell had broken loose,” he says. This time, the children were clamoring that Leslie was a witch. Why else would he wander and talk to himself in such an astonishing way?

For Leslie, professor of anthropology, this small episode illustrates a larger problem he studies — the clash of old and new. After many generations of herding their animals across the savanna, Maasai people are forbidden to live in the Serengeti National Park. Conservation groups believe Maasai represent a threat to Serengeti’s wildlife — wildlife that now attracts 500,000 tourists and more than $700 million a year to Tanzania.

While Leslie is all for conserving wildlife, he points out that the Maasai are a part of Nature, too. “That area in northern Tanzania is where you get the stereotypic African experience — the zebras and elephants and lions and the lone Maasai herder standing on one leg with his spear, overlooking the plains,” he says. “And people see the savanna as natural, and we try to preserve it in parks. But humans have been herding their animals in that environment for hundreds or thousands of years, and there’s good reason to believe that what we see as natural is at least in part a product of human actions.”

Leslie points out that herders have for generations burned the grasslands because the new growth is tender and lush. “If you exclude humans and their herds, you sometimes see a change in the grasslands toward more scrub brush and more species that do better in the scrubbier brush. So you may get fewer gazelle and more wildebeest and then more cape buffalos, for example.”

In Tanzania, the conflict pits those whose top priority is wildlife conservation against those who believe that indigenous peoples like the Maasai have a right to maintain their way of life. Leslie says he has to be careful not to seem to fall into either camp as he interviews Maasai people and studies their culture.

“Our research depends on good relations and our ability to talk with people,” Leslie says. “If we’re perceived as being part of the environmentalist camp, people won’t want to talk to us.”

If a resolution is possible in the conflict over the fate of Maasai in Tanzania, it may well arise from the kind of knowledge Leslie and his students and colleagues are seeking. While each faction in Tanzania has a theory about the effects Maasai have on the environment, no one really knows.

Leslie explains that Maasai have been implicated in the two foremost threats to wildlife in the region — farming and hunting. Even though traditional Maasai are herders, not farmers, some of the farmers moving into the Serengeti before the expulsion were closely related to Maasai. And while Maasai generally don’t do a lot of hunting, they have killed lions when their herds were threatened. Young warriors traditionally have shown their bravery by taking on lions with spears, Leslie says. “So there are some legitimate concerns over the impact on wildlife. But I think the conclusion was a bit overdone. The actual fate of the Serengeti National Park and the other parks in northern Tanzania, and the resources and wildlife there, are influenced by a number of factors, of which the Maasai are only one.”

In recent decades, conservation interests have succeeded in banishing Maasai from large areas of their traditional lands, including the Serengeti National Park. Confined with their herds into smaller areas, Maasai have begun turning to agriculture to supplement their diet. Leslie’s team is studying the consequences — for Maasai families and for the environment.

“These parks and conservation areas, where all the fantastic wildlife is, can’t really be treated as isolated systems because the animals don’t know about the park boundaries, and some of them have to migrate in the dry season to other grazing areas,” Leslie says. “Pastoralists can live in a place and intermingle with the wildlife, but sometimes they have to get out of the way. The wildebeest, for example, have huge migrations, and when the wildebeest calve, they spread, through nasal secretions and so on, a disease that’s lethal to cattle. So Maasai herders have to stay away from the wildebeest during certain times of the year. But if you are planting fields in these wildlife corridors, what’s going to happen? People don’t want fifty thousand wildebeests or even a few elephants running through their fields.”

One of Leslie’s graduate students, Amy Cooke in the Ecology Curriculum, is working outside of Tarangire National Park, where Maasai are adopting agriculture. Cooke studies how people choose where to farm, and she examines farming’s effects on the migration corridors of key wildlife species. “We really need to know a lot more about the ecology of these systems and, unfortunately, we’ve got to know yesterday,” Leslie says. “This is happening right now, it’s happening very fast, and it’s a real race. If we want to have any sort of a rational response to human population growth and economic change and the desire to conserve, we’ve got to know a lot more.”

In the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, the government has attempted to ban agriculture or at least to limit it severely. Leslie’s team is comparing the effects on people and the environment inside the conservation area with those outside it. The team is also studying the changes that result as more and more Maasai, especially young men, gravitate toward towns.

“They find work especially as watchmen and guards because they have a reputation of being fierce warriors,” Leslie says. “So they go there with the idea of earning some money, buying some animals, adding to the family herd, and getting married. Sometimes it works out, sometimes it doesn’t. But in addition to bringing back animals, they are also bringing back new expectations and values, and maybe a source of income. So they are less dependent on the elders, and their social system is going to change. They are also bringing back microbes, and HIV is now just getting into this area.”

Leslie collaborates with Trude Bennett, associate professor of maternal and child health; with Ipas, a Chapel Hill-based organization that works with women’s reproductive health; and with two Tanzanian hospitals that have mobile health-care units. The team gathers information from medical clinics in remote areas to study maternal mortality rates, to track pregnancies, and to test for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

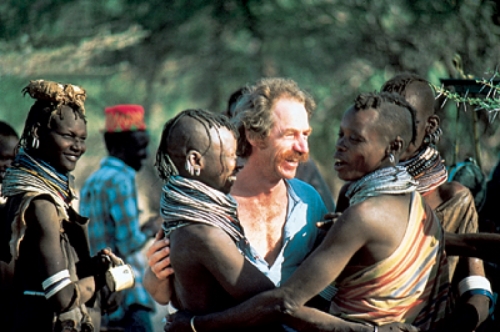

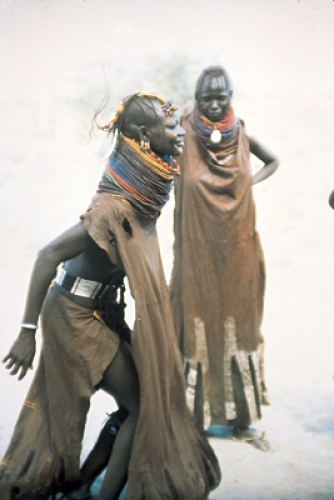

In all of this work, Leslie adopts the perspective of a human ecologist — someone who studies people as a part of their environment. And he’s been doing this kind of research much of his career. For 15 years, from 1980 to 1995, Leslie was part of a team of social scientists and ecologists studying people from the Turkana region of northwestern Kenya. The project, whose results have been published in part in Turkana Herders of the Dry Savanna (edited by Michael A. Little and Paul Leslie and published in 1999 by Oxford University Press), dispelled some long-held assumptions about the herders and their animals.

“For a long time, Western policy makers and scientists have had the picture that African pastoralists are not really rational herders,” Leslie says. “The pastoralists keep as many animals as they can, and they have big herds with lots of scrawny animals that often look like they are just walking skeletons. So the development expert goes in there and says, ‘Well, these guys don’t know what they’re doing. They’re keeping too many animals, they’re overgrazing, and they’re causing desertification — spread of the deserts.’ But in Turkana, we found no evidence of that, except in the few cases around towns or missions where wells have been drilled, and then people congregate, and you do get overgrazing.”

By combining the tools of diverse fields, including biology, ecology, anthropology, hydrology, and medicine, the Turkana project could examine the people and their environment from multiple perspectives. For example, ecologists watched animals nibble bushes or built exclosures to keep animals away, studying the effects on vegetation. Anthropologists observed people day by day, asked them about their animals, their decisions, and their social arrangements. In combination, the studies yielded a comprehensive picture of life in Turkana.

This approach — to study people as a part of the ecosystem — was a new idea when the project began. Ecologists of the time tended to regard human beings as intruders and despoilers, and researchers typically sought out pristine systems undisturbed by people. But in Turkana, Leslie and his colleagues found a system in which people were inseparable from the natural order of things. As Leslie writes it in the first chapter of Turkana Herders, the landscape of northwest Kenya conveys “an image of linearity and sharpness. The people are tall and thin, the dogs are scrawny, the rocks are sharp, and the trees are covered with thorns.” But in these harsh environs, where life seems precarious at best, Leslie and his colleagues found a logical system at work.

Take, for example, the little round clumps of trees that dapple the savanna. Ecologists found that these clumps of trees are about the same size and shape as the thorn-fence corrals that herders use to pen up their animals and protect them from predators during the night. Inside the corrals, the animals drop their manure and tromp it into the ground, preparing the soil for the tree seeds that pass through their guts. When the herders have gone, the thorny corrals remain, protecting the circle of ground and giving the seedlings a head start.

“So what’s really happening,” Leslie says, “is that the animals are transporting nutrients from all over the landscape and depositing them in these corrals. And if you climb up to the top of a hill in Turkana, shortly after the rains, you can see circular patches of green that are the same diameter as these old corrals.”

And Turkana people keep those big, scrawny herds for very good reasons. In their culture, animals represent the collective wealth, not only of individuals, but of families and groups. Borrowing and sharing are customary and expected, and marriages demand a transaction of as many as 75 large animals such as cattle and camels and perhaps 200 goats. These customs arose from an environment in which people “count on disaster,” Leslie says. A Turkana family knows that drought, intertribal raiding, or livestock epidemics will almost inevitably wipe out some or all of the family’s animals. A network of shared obligations reduces the risk of catastrophe for any one family, much as insurance does in Western industrial cultures.

“What people are maximizing is not productivity but the probability of persistence,” Leslie says. “Under the circumstances, it wouldn’t make sense for them to have fewer, fatter animals because people wouldn’t be able to build those networks.”

So are the hungry animals denuding the environment and spreading the desert? No, Leslie says. “What’s controlling the populations of the animals is something that’s extrinsic to the system itself, and that’s rainfall. When there’s a drought, and there’s nothing for the animals to eat, their numbers get knocked down. Not all ecosystems are like that, but a lot of the dry lands of Africa are.”

Some of the studies were “endlessly entertaining to the Turkana,” Leslie says. Ecology students followed the camels around, weighing their dung, measuring the nutrients. Hydrologists studying water-percolation rates trucked water into the dry bush with a Land Rover, dug a series of holes, poured a measured amount of water into each, and then timed the water with a stopwatch until it disappeared.

“So the Turkana guys are watching all of this,” Leslie recalls, “and they say, ‘What’s with this guy? How many times you gotta pour this water in there? I’ll tell you what’s gonna happen, it’s gonna disappear.’”

Leslie made a little more sense because he talked with people about things that were important to them — why they took their animals here instead of there, or why they had this mix of species in their herds rather than having more camels.

While Leslie’s team was studying the effects of people and their animals on the environment, they were also interested in how the environment affected the people. They measured growth and development in the children — height, weight, fatness, and immune-system function. They also studied fertility to learn how the environment might have been affecting the reproductive function of women and men.

“You assess that by measuring hormone levels at different times, and that entails taking urine samples and blood samples, which can seem a little odd to them,” Leslie says. “If we hadn’t already worked there for years, I never would have been able to get the blood samples from them. As it was, it took a lot of explaining to really make sure they didn’t think we were doing some sort of witchcraft.”

Studies in Turkana and elsewhere have challenged the notion that fertility is determined by social factors alone. Comparing nomadic and settled women, Leslie’s team found significant differences in reproductive function, some of which appeared to be environmentally induced. “Among the most striking of our results is an extraodinarily high rate of pregnancy loss among settled Turkana women, but not among the nomads,” Leslie says.

Work in this field, which is called reproductive ecology, is relatively new, Leslie says. And not all social scientists are comfortable with it, or with any other approach that would seem to imply that biology influences human behavior. In some universities, disputes over such questions have split anthropology departments apart, creating what Leslie regards as an unfortunate division between cultural and biological anthropologists.

“Here (at Carolina) it is much, much better,” Leslie says. “We have people who do work on both sides. Sometimes there are tensions, but we still like each other and go to the same parties, and we encourage our students to bridge those perspectives.”

These days, some of those students may wind up working with Leslie in Tanzania, but Turkana is off limits, for now. The area has become too dangerous, racked with ethnic and political violence. “Livestock raiders running around with spears is one thing,” Leslie says, “but when they’ve got AK-47s, that’s another.”

That’s a shame, Leslie says, because during his 15 years in Turkana, he made friends and earned the trust of the people he studied. He had also invested a big chunk of his life, learning the people and the landscape, and mastering the fine art of automotive repair in the bush. (He’s spent untold hours under the working end of a Rover, his legs poking out in the sun.) Things are different in Tanzania, among the Maasai. The vehicles are more reliable. The land is richer, better watered. And the people do not range as far with their animals.

But in Tanzania, the issues are even more urgent than they were in Turkana. The Maasai and their way of life hang in the balance. Will they give up herding and settle for farming? Will their health decline as they grow more sedentary, more dependent on corn? Will their values and strong social networks decay?

“Tanzania is a wonderful place to work because it’s spectacularly beautiful,” Leslie says. “You drive to work through herds of elephants and zebras, and it’s just gorgeous. But there are serious problems there, and in some ways it’s very depressing to see what is happening to the people. They are bearing the entire burden of the conservation efforts. They are losing their livelihood. And it’s all because they happen to be living where there are some pretty animals.”

Neil Caudle was the editor of Endeavors for fifteen years.

Leslie’s research is funded primarily by the National Science Foundation, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and the Rockefeller Foundation.