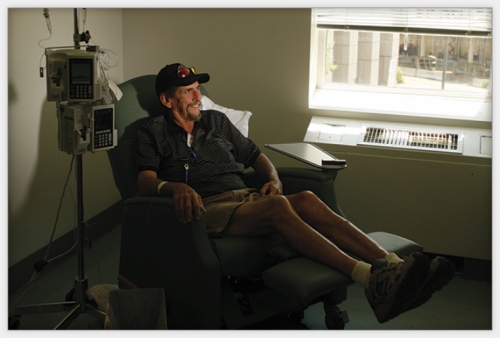

Tomma Hargraves rubbed her sore neck and felt a hard knot. Her family doctor said it was probably nothing serious, but to be safe he ordered a biopsy. The knot was a malignant lymph node. Hargraves had lung cancer — stage 3b non-small cell carcinoma.

Her husband Bob searched the internet and found out that many stage 3b lung cancer patients who get standard care — chemotherapy, sometimes radiation — die after one year. Some stories online told of even worse prognoses.

“My husband thought that I was as good as dead,” Hargraves says.

Their son Josh, an emergency-room doctor, told his mom to get three opinions.

The first doctor said there was little he could do other than give her chemotherapy every three weeks.

“No radiation?” she asked. “No surgery?”

Not for someone in her situation.

The second doctor offered Hargraves a clinical trial that included chemotherapy and radiation.

For her third opinion, Hargraves went to Mark Socinski at UNC. His clinical trial was very different, an aggressive nine-month protocol that had never been tried before. Hargraves started that trial in December 2006, two months after her diagnosis.

Socinski gave Hargraves one heavy dose of standard chemotherapy, then another three weeks later. Her hair fell out; she lost weight. But the tumors shrank, a sign Socinski knew had boded well for previous patients in his trial.

Hargraves rested for two weeks before starting a seven-week regimen of chemo every Monday and radiation every weekday. The radiation doses were 12 percent higher than in standard care. At the same time, she took a new drug called Tarceva to keep microscopic cancer cells from spreading throughout her body.

In May 2007 the tumors were gone. Socinski found no cancer cells in Hargraves. But the trial wasn’t over. For the next eighteen weeks she took Tarceva and Avastin, another new drug designed to keep tumors from reforming.

Fourteen months later Hargraves was still cancer-free. She celebrated her sixtieth birthday in July.

“Doctors don’t like to use the word ‘cure’ when it comes to cancer,” she says, “so they say I’m acting like a cured patient. That’s good enough for me. I might be wrong, but I truly believe that had I not been in that trial I wouldn’t be here today.”

Stories such as Tomma Hargraves’ are why doctors do research — to help their patients live full lives for as long as possible while testing drugs and regimens that might help other people those patients will never meet. But getting results takes more than hope and intellectual curiosity.

Just gaining approval to do a clinical trial is a tedious process. Research studies take time, sometimes the better part of a decade. Late-stage trials that aim to change clinical practices can be double-blind: patients don’t know if they’re receiving new treatment, standard care, or a placebo — and doctors don’t know either. Recruitment for these studies can be difficult because some patients don’t want to participate if they won’t know which treatment they’re getting.

Some people refuse to join research studies for fear of being guinea pigs. Others don’t live near hospitals that conduct clinical trials, which makes it difficult to participate in research and try the new therapies they may desperately need.

“I live very close to three very good hospitals,” Hargraves says. “I know there are a lot of people in rural areas who don’t want to make that trip.”

Photo by Coke Whitworth; ©2008 Endeavors.

Click to read photo caption. Photo by Coke Whitworth; ©2008 Endeavors.

Why UNC?

Hargraves is right; she’s fortunate to live in the Triangle. According to Shelly Earp, director of UNC’s Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, about 3 percent of cancer patients in the United States are part of clinical trials. That number jumps to 18 percent at UNC and other academic centers that are trying to improve upon standard treatments that just aren’t good enough.

Not all patients fare as well as Hargraves — stage 3 lung cancer is extremely tough to beat, and some of Socinski’s trial patients died. But as Earp says, “We don’t do trials for diseases that are perfectly curable.”

Earp says that of all the issues involved in clinical trials, the one thing he wishes more people knew is that research participants receive special care. Several physician researchers and research nurses, in addition to regular clinical staff, look out for the patients. In fact, each patient is assigned a nurse coordinator who’s on call twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.

While taking Avastin, Hargraves had a severe nosebleed that scared her so much that she contacted her nurse coordinator Maureen Tynan, who told Hargraves how to stop the bleeding and reassured her that a profuse nosebleed is a common side effect.

Tarceva can cause terrible skin irritations — dandruff of the body, as Hargraves calls it. Tynan put Hargraves in contact with a dermatologist who is familiar with Tarceva. Tynan was the one who set up all of Hargraves’s appointments, reminded her when her next consultations were, and made sure she reported every detail that the trial protocol demanded.

“The care that clinical trial patients receive is at least as good as, and often better than, the care regular patients get,” Earp says.

UNC sends information about available clinical trials to physicians around the state and encourages them to consider conducting trials at their clinics.

“We’re developing access to clinical trials for Rex patients and will soon have a joint program with East Carolina’s cancer center,” Earp says. “There are certain kinds of trials that you can only do under close monitoring at an academic center.”

Right now, even if doctors outside of a trial know about a promising new therapy, those doctors must follow the guidelines for standard of care. If they don’t, they could leave themselves open to malpractice lawsuits. And insurance companies often don’t pay for therapies outside the realm of standard care.

For the more aggressive trials, such as Socinski’s, an experienced staff should monitor all aspects of the protocol because toxic side effects have to be managed by people who have seen them before.

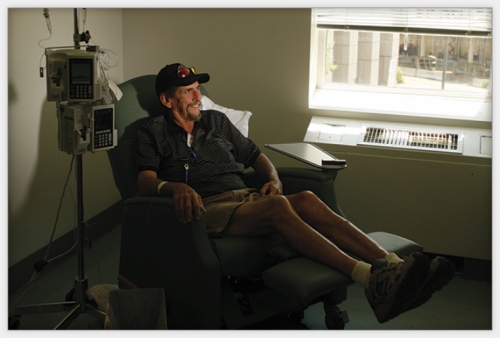

Don Yarborough weighed 250 pounds and stood 6-foot-5 when he came to UNC for a liver-cancer trial. His body rejected the first chemo treatment.

“I just broke out like a big fat strawberry,” says the sixty-two-year-old Vietnam War veteran. “I got humongous welts all over my body and I turned red in the face and ears.”

Bert O’Neil, Yarborough’s doctor at UNC, cut off the chemo immediately and didn’t think he’d restart it. But Yarborough insisted on being part of the trial. If the treatment didn’t help him, he said, maybe the research would help someone else.

“Well,” O’Neil told him, “it’s going to change your quality of life.”

“But it really hasn’t changed my quality of life,” Yarborough now says. “I’ve been so blessed.”

Yarborough has been part of O’Neil’s liver-cancer trial since September 2007, about four months after routine blood work revealed something wrong with his liver. Duke oncologist Carlos Marroquin performed laparoscopic surgery, but the tumor had invaded the portal veins that feed blood to the liver. Marroquin told Yarborough that he probably had two months to live. But Marroquin also told him about Bert O’Neil’s clinical trial.

When Yarborough broke out with that rash but demanded to continue, O’Neil admitted him to UNC Hospitals so that nurses could slow-drip the chemo into his bloodstream overnight. It worked. Over the next few weeks Yarborough’s reaction diminished, thanks in part to an antihistamine. He now absorbs that same chemo in one hour, which makes his weekly trip from Wilmington, North Carolina that much easier.

Every Friday Yarborough’s brother Charlie picks up four dozen Krispy Kreme doughnuts for the clinic crowd before swinging by Don’s house at 4:30 a.m. to be at UNC by 7 o’clock. “Charlie and I, we’re both a couple of idiots,” Yarborough says. “We cut the fool all the time and we just keep ‘em rolling up there. But I’m going to tell you something: Doctor O’Neil’s group and those nurses are as fine a bunch of people as you will ever meet in your life.”

Yarborough takes three different kinds of chemo every third Friday and two kinds on the other Fridays. Two out of three weeks, he takes chemo pills every day. The therapy caused him no side effects for six months until, in April, he lost his appetite, started having digestive problems, and began feeling numbness in his fingertips and toes. Ten months after Yarborough started the trial, he had lost fifty pounds. If he loses any more weight, doctors might stop the treatments. He can’t work his carpentry job because he can’t bend over without pain; fluid surrounds his stomach due to his damaged liver.

But each MRI has shown that his tumor has either shrunk or stayed the same.

No one knows how much time he has left. No one knows if this clinical trial will give future liver-cancer patients another treatment option. But Yarborough has already lived eight months longer than anyone thought he would. And he says he still feels good.

“What I’m hoping for is that, with so much chemo, the tumor will say ‘enough is enough’ and start shrinking again,” Yarborough says, smiling. “This could go on for a while until it either kills me or heals me.”

Photo by Coke Whitworth; ©2008 Endeavors.

Click to read photo caption. Photo by Coke Whitworth; ©2008 Endeavors.

The paper trail

O’Neil’s clinical trial is one of thirteen his unit is now running on gastrointestinal malignancies. At Lineberger there are more than one hundred studies under way that range from basic biological research on tumor samples to aggressive, complex clinical trials, some of which involve researchers and patients from across the country.

O’Neil was under no illusion that his study would uncover some sort of cure; he hypothesized that combination therapy would prolong patients’ lives. It has taken O’Neil years to turn that idea into preliminary research data. The process hasn’t been easy.

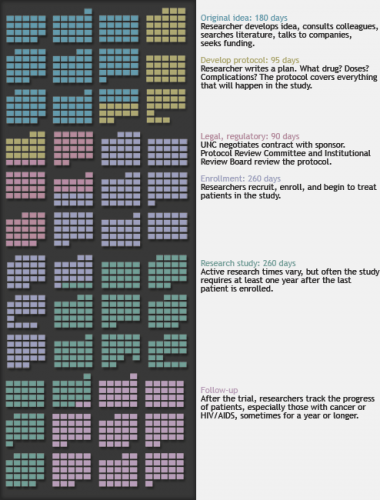

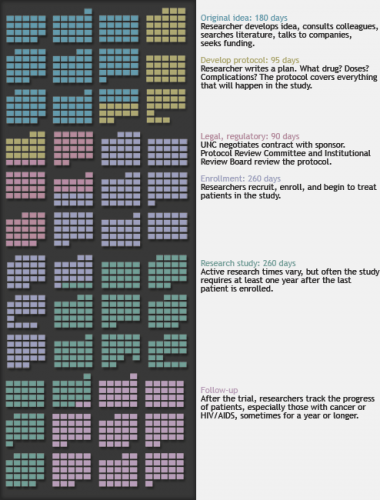

This timeline of calendar pages, covering four years of work days, represents the stages of a hypothetical clinical trial — in this case, a drug trial. Colors indicate different stages.

Click to read photo caption.

“For those of us who are honest people interested in patients and don’t have any agenda other than wanting to advance science, the regulation for clinical trials is immense and immensely burdensome,” O’Neil says.

But the reasons for such strict guidelines, he says, are that around the world some researchers have overstepped the bounds of protocol, and some studies have gone terribly awry.

In 2006 a British pharmaceutical company was testing a new anti-inflammatory drug when several healthy participants suffered massive organ failure. The United Kingdom’s drug regulatory agency determined that researchers failed to follow protocol in several ways, but that such negligence did not lead to the unexpected biological reactions. BBC News, though, quoted experts who said the reactions should have been expected because the potential effects of the drug had been listed in scientific literature.

The study in Great Britain was a Phase I trial, meaning that the drug had been tested only on animals. UNC conducts Phase I as well as later-stage trials, but no matter the risk level, every trial must follow the same guidelines and procedures, starting with the search for funding.

Earp says that over the past decade the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has granted more money for clinical trials. The National Cancer Institute funds some of Lineberger’s trials through a core grant supporting the protocol office that processes every cancer trial at UNC. “However,” Earp says, “the largest single source of support comes from private donations to the center from donors who want to see scientific innovation turned into new therapies.”

A third major funding source is industry. For example, a pharmaceutical company funds Socinski’s trial. As Earp says, the best place to test new therapies is an academic center that’s searching for good treatments and solid data.

But drafting the contract between UNC and a drug company can be a drawn-out process, says Barbara Longmire, director of UNC’s Office of Clinical Trials. And negotiations can add to the already lengthy approval process.

“We’re constantly trying to educate our faculty to know what a trial will cost because if they end up spending more time on the research than expected, somebody here is going to cover that cost,” she says. “That’s not to say that we can’t take a study that’s going to be a financial loss, but we need to know that going into it.”

After the funding agency approves a cancer-trial protocol, it’s sent to Lineberger’s protocol review committee, a group of two dozen experts who make sure each trial at Lineberger asks good scientific questions and uses sound scientific methods. From there the protocol might be sent to the General Clinical Research Center, a UNC group that assists faculty in many ways (though not all researchers at Carolina use the center).

UNC’s Institutional Review Board has its say to ensure the rights and welfare of all participants. The protocol then goes back to the funding agency for re-approval.

All this can take longer than a year, which is why some drug companies and private research firms conduct their trials overseas, where researchers may have to follow FDA guidelines but can still save time and money.

“Depending on the research site, a researcher may not have the same level of bureaucracy and approvals that are required for trials stateside,” Longmire says. “Start-up is often a lot faster at foreign sites. And depending on where researchers go, and the disease area being studied, there could be a much larger ready population that’s willing to participate in clinical trials.”

But Longmire says that university-based trials are still the gold standard because academic centers have “highly trained clinicians who know how to do research, and do it well, while supporting the university’s larger mission.”

The School of Public Health is trying to speed up the entire clinical trial process at Carolina with its Center for Innovative Clinical Trials, which brings together dozens of UNC researchers to figure out how to get trial approval more quickly and turn research findings into clinical practice faster. And in June 2008, UNC received a $61-million grant to become part of NIH’s Clinical and Translational Science Award consortium. Part of the grant will help researchers reduce the time it takes to turn their discoveries into treatments for patients.

Photo by Coke Whitworth; ©2008 Endeavors.

Yarborough takes chemo pills every day for two weeks, then has a one-week break.

Click to read photo caption. Photo by Coke Whitworth; ©2008 Endeavors.

Clinician versus researcher

When O’Neil talked to Yarborough about his odds for survival on regular treatment, Yarborough asked to join the clinical trial. Often the decision to volunteer is much tougher, and the doctor has to walk a fine line between the roles of clinician and researcher.

Joe Eron, who studies new HIV/AIDS therapies, sees hundreds of patients at UNC’s HIV clinic.

“When I talk to patients about a clinical trial,” Eron says, “the very first thing I tell them is, ‘No matter what I say in the next five minutes, and whatever you do or don’t want to do, I’m your doctor and I’ll be your doctor whether you want to do this trial or not. It doesn’t matter to me.’ I want them to feel free to say no because I’m in this powerful position and many patients have different levels of sophistication. And I really don’t want to hear, ‘Whatever you say, doc.’”

Eron says that some HIV/AIDS trials test a combination of therapies that are considered the best drugs available. But right now Eron is running a trial to see if intensified therapy can drive the virus load below the point that doctors can measure. Standard tests can’t detect HIV below a certain amount of virus in the blood. But there’s an experimental test that can detect HIV down to one virus copy per milliliter of blood. Eron is using that test and a new drug called Raltegravir to see how low the virus load can be pushed.

“We would never offer this to a patient outside the clinical trial,” he says. “In this case, I have to really hear from patients that they completely understand that this experiment could have risk and no benefit. We enroll fewer patients in this kind of study. We need fifty; we have forty-three. We’re getting close.”

He says that some patients, depending on their treatment histories, shouldn’t be enrolled in this kind of study even if they meet the trial’s general criteria. But patients often see ads for a trial and want to join, sometimes for the money. This, Eron says, gets tricky. The patient might really need that cash.

“I have to be careful,” he says. “They can’t do it solely for the money. I’ve been in situations where I’ve had to say, ‘The trial is not really good for you.’”

The flip side, Eron says, is when a research assistant knows that a patient is a prime candidate for a clinical trial, but the physician disagrees and doesn’t tell the patient about the trial. And that might be fine, Eron says, because the doctor might know the patient really well.

“Or it might be that the clinic is really busy and if a clinical trial coordinator is going to come in and talk to the patient for an hour, this will slow things down,” Eron says.

“I feel that the patient should participate in that decision, and I get worried that we sometimes assume we know what people want,” he says. “There’s a subset of patients who are extremely knowledgeable about HIV, and when you tell them there’s an opportunity to learn something that no one else knows about their disease, there’s a surprising amount of interest.”

Some patients actually do better during a clinical trial than they do afterward, even if the prescribed therapy is the same.

One patient we’ll call Keith was diagnosed with HIV in 1997. He’s been in ten drug trials at UNC and each time one ended he got worse.

“I’m much more diligent about taking my meds when I’m in drug studies,” Keith says. “For one, someone’s buying the drugs for me so I feel obligated. Two, I don’t want to let them down. And three, they monitor me; I have accountability. When I’m not in a study, I’ll forget to take a pill here and there.”

Searching for answers

Keith is in one trial that will continue until he dies, even if that’s of old age. Researchers will collect all the data from Keith’s many treatment regimens to see how he responded to various drugs during the course of his disease.

One of Eron’s more typical combination drug trials takes a few years to finish. Getting a novel drug through the three main phases of a trial — laboratory testing, animal testing, and human trials — and into clinical practice can take a decade or two.

Other kinds of research studies that don’t involve drug approval can take just as long, such as prospective studies that try to figure out causes and risk factors for diseases.

In the School of Dentistry, Bill Maixner heads up a seven-year Phase I study on temporomandibular joint disorder — TMJD — a chronic pain condition caused by inflammation where the upper jaw meets the lower jaw. Doctors aren’t sure what causes it.

Maixner’s $19-million grant includes three other universities — Florida, Maryland, and SUNY at Buffalo — all of which are recruiting eight hundred people each. But the volunteers aren’t patients; they’re beginning the study as healthy controls. Maixner predicts that about 3 percent will develop TMJD during the study, and the information gleaned from these people could help researchers figure out what causes the condition.

Maixner designed a battery of tests and questionnaires that measure pain sensitivity, anxiety, depression, and other potential risk factors. The tests take three hours. Then his team tracks participants for five years, asking them questions every three months about their mental and physical health. This information should give researchers enough data to pinpoint exactly what happens to those few who develop TMJD. Some participants are called back to the clinic for more testing. And each participant gives blood so researchers can look for genetic markers of risk factors.

“If we can identify biological pathways that cause TMJD, then we can start to think of therapeutic targets,” Maixner says. “We can begin to think of new drugs or maybe even how to use drugs that are already on the shelf for other conditions.”

Researchers might also be able to find out why current TMJD treatments, such as behavioral therapy and antidepressant medication, help some people but not others.

Maixner’s team in Chapel Hill had no trouble finding volunteers for the study because the protocol is fairly benign, though volunteers are poked and prodded so that researchers can measure pain sensitivity.

Recruitment for other studies is much trickier. Clearly, not many healthy people are willing to volunteer to test the toxicity of a new drug, which is why such trials offer more compensation. But recruitment also isn’t easy for trials that test known drugs.

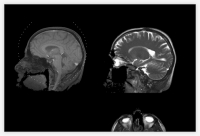

Researchers in Carolina’s psychiatry department are trying to figure out what happens in the brains of people with mental illnesses, especially when they take medications that have been on the market for years, such as lithium.

Kelly Smedley is the program coordinator for several bipolar disorder studies. For one, her team needs to recruit ninety people with bipolar depression and another sixty for the control group. By July 2008, twenty-six controls and sixteen bipolar depression patients had volunteered; seven others had dropped out.

“It’s very difficult getting people to do these medication studies,” Smedley says, “because many patients are concerned that it’s a study and that the medication is being tested on them.” Once enrolled, some patients couldn’t stick to the trial’s fairly rigorous protocol.

Researchers use a standard three-hour psychological test to make sure all participants fit the research criteria. All bipolar patients who qualify get an MRI, which takes about two hours. Then they’re treated with lithium for four weeks before getting another brain scan. Those who respond to the lithium treatment continue to take it. Those who do not respond are given lithium and lamotrigine, which the FDA approved in 2003 for some bipolar depression patients. All patients get another MRI twelve weeks later, and all patients must go to ten 45-minute sessions at the clinic.

Beliza Powell, who has battled manic depression for years, didn’t mind the protocol despite having to drive to Chapel Hill from Sanford, North Carolina.

Last winter she fell into a deep depression. She saw no hope and found no joy, not even in her grandkids. She says she contemplated suicide and knew that if she didn’t get help, she wouldn’t make it. Doctors in Sanford told her to go to UNC’s psychiatric emergency walk-in clinic, where she was told about the bipolar study. She agreed to join and started taking lithium.

“I began to feel better immediately,” says Powell, who finished the study but still takes lithium. “What I really liked about the program is that they educated me, talked to me through the whole thing. They helped me understand what the disorder is, why I was this way, and that I could live a normal life. I’m still taking lithium and I feel normal. I have my good days and bad days like everyone does. I have hopes and dreams. I’m living.”

During the study, Powell experienced blurred vision, tiredness, heartburn, and hot flashes. Smedley says that some people dropped out of the trial due to side effects, especially lethargy, but Powell says her side effects subsided quickly.

One of her worst days was when she had a panic attack in the MRI machine.

“But I told myself I was being silly,” she says. “They gave me a movie to watch in there and then I was fine.”

Healthy controls also get MRIs at the beginning of the study. The first twenty people enrolled get a second MRI at week four and a third scan at week sixteen (see “My brain on magnets”). The idea is to compare what’s going on in the brains of patients and controls because even though lithium and lamotrigine are common medications, scientists don’t really know how they work in the brain.

The trial is the first-ever controlled study to focus on the relevance of abnormalities in the frontal-limbic area of the brain and how that area responds to mood-stabilizing drugs over the course of several months.

From a recruitment standpoint, the protocol can be a tough sell — why not just take lithium and see what happens? Most bipolar depression patients who volunteer do not come from the psychiatry clinic.

“We have ads on TV and radio, in newspapers,” Smedley says. “We have flyers in libraries and grocery stores. We post on Craigslist, which has been successful and free. And we send e-mails to UNC staff and faculty. All of it approved through IRB.”

Ready and willing

Back at Lineberger, researchers get most of their trial volunteers from the clinic. Tomma Hargraves was two months removed from her nine-month-long lung-cancer trial when Mark Socinski asked her if she’d consider joining a Phase III randomized clinical trial for Stimuvax, a new drug that doctors think may stimulate the immune system to prevent cancer from returning. The trial includes thirteen hundred patients from thirty countries. Hargraves didn’t hesitate to volunteer, even though it’s a double-blind study.

“I know the nurses are frustrated because patients don’t want to come to UNC for the trial unless they’re guaranteed to get the active treatment,” Hargraves says. “How else are we going to know if these things work or not unless somebody’s willing to be a guinea pig?”