In 1995, less than 1 percent of the world population had access to the Internet. Today, approximately 40 percent of people can get online — that’s 3.5 billion users. During this time, online chatrooms have slowly evolved, from MUD gaming servers in the late ’70s, to the AOL Instant Messenger days of the ’90s, to the social networks of today. Now, nearly every platform has its own chat function.

Most of us can relate to the bittersweet beauty of constantly logging on — the negative commentary, little to no censoring, and the struggle of online addiction. But for those of us dealing with more serious compulsions — such as drug and alcohol abuse, depression, and eating disorders — the Internet becomes, to many, a hub for disclosure. Reddit, for example, has a series of sub-forums where drug users anonymously discuss everything from colorful anecdotes to advice for recovery.

About 10 years ago, Cynthia Bulik — the founding director of UNC’s Center of Excellence for Eating Disorders — was quick to recognize the benefits of this technology. In 2008, she appointed Stephanie Zerwas, an eating disorders researcher and clinician, to coordinate the project. Zerwas teamed up with researchers from UNC’s psychiatry, biostatistics, neurosurgery, and nutrition departments to study the outcomes of online chat therapy on people with bulimia nervosa. This serious, potentially life-threatening eating disorder is characterized by purging after overeating.

The most effective treatment for bulimia is cognitive behavioral therapy. Approximately 40 to 60 percent of people who complete this treatment show significant improvement, according to Zerwas. “But a lot of people don’t have an eating disorder specialist in their neighborhood — or even within a two-hour radius from where they live,” she points out. “We wanted to see if we could deliver the treatment in a way that people could do it from home.”

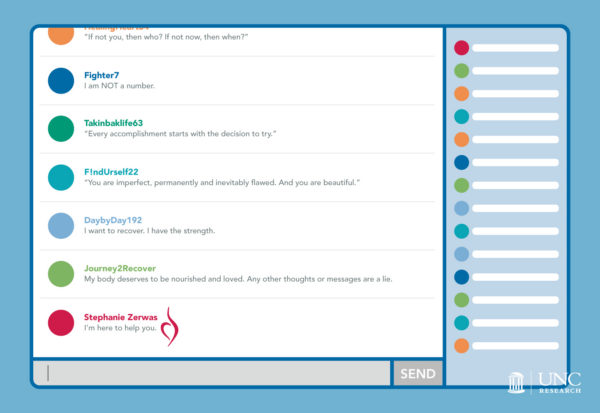

Intrigued by the growth of online chat groups, Bulik, Zerwas, and their team incorporated the social mechanism into the 2008 study. They solicited a group of 196 adult patients with bulimia, who were randomly divided into two segments — one attended weekly face-to-face group therapy sessions, while the other received therapy within an online chat group. Both parties received up to 16 therapy sessions over the course of 20 weeks.

At the end of treatment, it was obvious that the face-to-face group produced better results. But by the one-year follow-up appointment, the gap in treatment had narrowed. Online participants were at the same level of recovery as those who participated in the face-to-face therapy sessions.

Online group chat therapy provides a level of anonymity that comforts many people with bulimia, who often struggle with feelings of inadequacy and social anxiety.

Creating safe, shameless spaces

One of the most common emotions associated with eating disorders is shame — which often leads to the act of binging and purging associated with bulimia. In fact, humiliation (a type of shame) produces a more intense emotional experience in the body and brain than happiness or anger, according to a 2014 study from the University of Amsterdam.

These feelings of inadequacy most likely stem from social anxiety, which is why group therapy — a more affordable option to one-on-one cognitive behavioral therapy — can be an intimidating feat for someone with bulimia. “I’ve had patients who struggle with social anxiety so much that they’re even nervous about traveling on public transportation to get to their appointments,” Zerwas shares.

Because the study randomly placed participants in either an online chat group or face-to-face intervention, Zerwas received a handful of concerns from patients who didn’t want to meet in person. “Many told me they might not want to participate if they didn’t get into the online group,” she says. “They didn’t want to go to the hospital to talk with a bunch of strangers about something they feel ashamed of.”

The anonymity of the chat group not only removed this stigma, but boosted empathy among participants. “I think you’d be surprised to see how emotional and empathetic the online group really was — because they didn’t have to worry about someone else’s facial reactions to what they were saying,” Zerwas explains. Other researchers who read through the transcripts were “blown away by the amount of emotion and disclosure, and the fact that it really felt like a therapy session.”

Choosing radical media

Since she began studying online chat therapy, Zerwas quickly grew interested in other social platforms. In 2015, she and Morgan Walker, a research assistant with the Center in Excellence for Eating Disorders, researched online body and weight dissatisfaction. It’s especially prevalent among college students, 20 percent of whom obsess about what they eat and how they look, according to Zerwas. Here’s what she and her team wanted to know: Does this era of online social media make us more obsessed with our body, shape, size, and weight than ever before?

“If you think about all the pictures we’re sharing right now, it’s so easy to make those comparisons all the time,” Zerwas says. “Facebook can be a really great way to build a social network and social capital and this supportive environment. But not all the time. If you’re using it to compare your life to your friend’s life, or your face to your friend’s face, or your thighs to your friend’s thighs — that’s really dangerous behavior.”

Zerwas and Walker gleaned three observations from their Facebook research. The first: Share don’t compare. Online body comparison is so common, according to Zerwas, that a series of hashtags promote it (i.e. #bodygoals, #bikinibridge, #thinspiration). “It’s a predictor for hating how you look and starting a really risky diet,” she says.

“In social media, you are the media — and you have more control over what you look at than ever before.”

— Stephanie Zerwas

Secondly, the camera lies. Zerwas demonstrates this at her 2016 TEDxUNC talk. An image on the screen shows six large magenta circles surrounding one bright, slightly smaller yellow dot. To its left, a second yellow sphere is encircled by six, much smaller magenta dots. The latter looks much larger than the first, but in truth they’re the same size. “For some reason we don’t realize pictures of our bodies can act the same way,” Zerwas says. “We are fooled by the relative size of objects.”

At the end of her talk, Zerwas reminds the audience to “choose radical media.” In other words: Stop consuming the same, negative content over and over again. “In social media, you are the media — and you have more control over what you look at than ever before,” she says. “Often, we don’t use social media to find new ways to interact with each other. We just use it to reinforce and duplicate our existing toxic media structure — a structure that’s overly appearance-focused.” Her point? We choose who we follow on Instagram, what we pin on Pinterest, and, most importantly, what we post about ourselves. So it’s up to us to create meaningful change.

Navigating borders and barriers

Although there were many benefits to the online group therapy, it didn’t come without problems. The safe space created by anonymity becomes problematic during times of crises, when a therapist needs to reach out to a patient beyond the fourth wall of the Internet. The integrity of the group may also be compromised by the possibility of negative comments or without a strong therapist to moderate the discussion. “We’ve all seen people write horrible things in forums or comment sections and get away with it,” Zerwas says.

Online therapy also creates new expectations around communication. People may prefer to set up appointments through text messaging, or even have access to their doctor 24 hours a day. “I think medical doctors and therapists used to have this idea of therapy being restricted to their room,” Zerwas says. “Then email grew in popularity and now they can receive messages from patients at 10 at night. What is the next level of technology going to do? Will it be the ability to text and talk constantly?”

Then come the difficulties of crossing state lines. Physicians, typically, are licensed only for the state they work in, so care ceases if their client moves out of state. The same holds true for online therapy. Before the study began, Zerwas received many requests from interested participants who lived out of state, but she wasn’t able to include them in the study because of licensing laws.

Internet security creates another hurdle — how can physicians guarantee their patients’ private disclosures remain safe? Any release of confidential patient files could be incredibly damaging for people with eating disorders, especially since they already suffer from feelings of shame and anxiety. “Whatever system gets used has to be really fool-proof and requires a lot of security,” Zerwas stresses.

Saving lives

Zerwas began this study one year after the release of the original iPhone. Since then, technology has morphed at an exponential rate. “I kept joking that, by the time this study got published, we’d be using holograms,” Zerwas chuckles.

She’s not far off. The Virtual Reality Medical Center in California, for example, uses virtual reality exposure therapy to treat panic and anxiety disorders such as fear of flying, claustrophobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder. For people with eating disorders, specifically, an app called Recovery Record helps them create and record meal plans, develop coping skills, and collaborate with their treatment team.

Although Zerwas hasn’t decided if she will pursue another study using online tools, her efforts still remain full force with eating disorder treatment and prevention. As the newly appointed clinical director of UNC’s Center of Excellence for Eating Disorders in January 2016, she wears two hats. In her research, she’s focused on the genetic link between anorexia nervosa and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), but in her clinical work, she is trying to improve early detection and intervention for eating disorders in North Carolina.

“We get pushback sometimes when we talk about genetics,” she explains. “Some say, ‘What we really need to do is fix our society to stop eating disorders.’ And there are some days I want to fix all of society’s problems. Having to watch families lose their children to eating disorders makes me realize I can’t fix everything — but I can try to fix one thing. I want to have better ways to detect and treat eating disorders so that our patients get back to health more quickly, so that they can help fix society’s problems. I want to empower them.”