“Lily and I autographed a five-hundred-pound bomb with an inscription, ‘Greetings to Japan.’ I hope it blasted the hell out of the Japs.”

Image courtesy of Lucy Kostelanetz.

Conductor Andre Kostelanetz and soprano opera star Lily Pons, who were married, performed for Allied soldiers all over the world.

Click to read photo caption. Image courtesy of Lucy Kostelanetz.

Conductor Andre Kostelanetz wrote that in 1945 when he and his wife, soprano star Lily Pons, toured combat zones with their orchestra, often competing with noise from bombers at nearby airfields. In Germany, days after American troops stormed toward Berlin, Kostelanetz wrote to a friend that antiaircraft canons provided “a reasonable replica of the bass drums at the most unexpected moments during the concert.”

Kostelanetz was one of many conductors and musicians who toured the front lines during World War II. But tales of their adventures and their music have gone largely untold. Musicologist Annegret Fauser says, “Never before had classical music received so much financial and ideological support from the U.S. government.”

Jason Smith

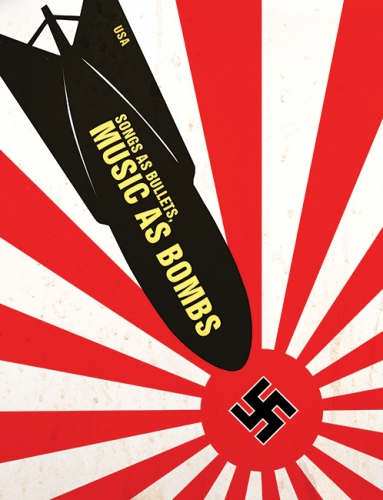

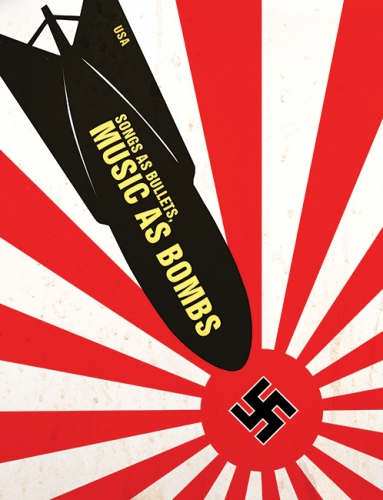

This illustration is modeled on a World-War-II-era poster titled More Production by an artist named Zudor. The original, which aimed to rally enthusiasm and industry for the war effort at home, was printed by the Government Printing Office for the War Production Board. It is now held in the National Archives.

Click to read photo caption. Jason Smith

The government believed in the power of music, she says. So did musicians. And so did soldiers. Music as therapy. Music as entertainment. For morale. As a weapon. For Fauser, conductor Serge Koussevitzky said it best in 1942: “We, as musicians, are soldiers, too, fighting for the ever-growing spiritual need of the world. If music is our life, we give it joyfully to serve the cause of freedom.”

Fauser was born in Germany almost two decades after World War II. “I’m a very typical German in that I don’t want to be German,” she says. “My generation is still part of that postwar world where the idea of national identity is hugely problematic.” The first chance she got, in 1987, Fauser left Germany to study in Paris, which is where she discovered letters between French composer Nadia Boulanger and her star pupil, the American composer Aaron Copland. Years later, after Fauser arrived at UNC in 2001, she started researching Copland’s era to serve as context for a book about those letters.

“I kept coming across really interesting texts about American music in the 1920s, the 1930s, 1950s, the 1960s,” she says. “There was this big hole—the 1940s. I thought that was strange; you could fill a whole library with books on music from Nazi Germany. So I thought, ‘This is not possible; I’m just a bad scholar and haven’t found anything yet.’”

She knew that some of Copland’s most iconic compositions were commissioned during the war. She found plenty on Copland but hardly anything about classical music during the war. Fauser, astonished, consulted with colleagues. They said, “All that stuff is just propaganda music.”

Mark Derewicz

Annegret Fauser: "The war was a boon for rank-and-file musical professionals who suffered through the Great Depression."

Click to read photo caption. Mark Derewicz

Fauser says, “I think some scholars didn’t want to embarrass themselves, because an awful lot of that music was blatant Americana. They’d say, ‘John Cage and others came afterwards, so we don’t have to deal with Morton Gould’s American Salute and stuff like that.’ But I’m not American. To me it’s an interesting cultural phenomenon.”

For five years Fauser spent summers, holidays, and long weekends rummaging through archives full of wartime correspondence, journals, news reports, and declassified documents. She realized that the kind of classical music being made was just part of the story, one she tells in her forthcoming book, Sounds of War.

“For the first time in their lives composers had commissions coming out of their ears,” Fauser says. And the government was a major funding source. There were Copland, Samuel Barber, Elliot Carter, Henry Cowell, and others, many of whom wrote classical music for the propaganda missions of the Office of War Information (OWI). Dissidents from Germany and the Soviet Union worked for the OWI too. Kurt Weill, for instance. He dubbed himself “formerly German” and worked hard for the American war effort, Fauser says, even though the government classified him as an enemy alien. Some musicians were classified the same way, and Fauser says many of them had to work harder than other musicians to prove their loyalty to the United States.

“Marc Blitzstein, whose music I absolutely adore, was a great composer who enlisted in the U.S. Army because he wanted to fight the Germans, especially after they attacked Russia,” Fauser says. Blitzstein, after all, was a communist sympathizer. He was attached to the Eighth Airborne in London, where he came up with the idea to write The Airborne Symphony, which the U.S. Army Air Forces commissioned for use in propaganda films.

One reason the federal government commissioned so much classical music was to combat the Nazi propaganda machine. “The Nazis made a huge point about the barbarians across the pond who listened to jazz and had no real culture,” Fauser says. This was a propaganda war about who had cultural superiority.

The U.S. government and musicians considered the United States to be the last bastion of freedom. “They’d say, ‘This is where all the great arts have now come to take refuge,’” she says. “‘We have the great orchestras, the great operas, the great singers.’” And the government had a point. Many composers and musicians had fled Europe for the States before the war.

But Fauser also found that combating Nazi propaganda wasn’t the only reason why the U.S. government poured money into classical music.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the military ballooned in size thanks to massive enlistments and the draft, which brought an influx of men from all walks of life.

“For the first time the government had about 17 percent of the population under its control, mostly in the military,” Fauser says. That’s ten million people, an armed force that mirrored the diverse American population. She says the military and OWI realized they could survey military men to get a good idea of what average citizens—at least the men—were thinking. In declassified documents, Fauser found that the military was curious about musical tastes. Swing was the most popular form of music—no surprise there. But number two was classical. “I had no idea that would be the case,” Fauser says. As she researched further, it made sense. After all, she says, “the Metropolitan Opera broadcast every Saturday afternoon to something like thirty million listeners.”

Fauser says that classical music, which was called “good music” in the 1940s, had a deeper appeal than other genres. Swing was for parties, and soldiers loved it. But when they wanted to feel uplifted, when they craved a sense of peace or calm, when they desired spirituality, they turned to classical music.

The army noticed. Fauser says that the first clinical trials of music therapy were held at Walter Reed Army Medical Center during the war. Results showed that music helped recondition soldiers. Not just any music, though. “Good music.”

In the National Archives and the Library of Congress, Fauser found the story of Harry Futterman, a professional accountant and amateur musician who started a charity to send libraries of classical albums to military camps stateside and abroad. Well-known conductors, such as Toscanini and Koussevitzky, sponsored the purchase of libraries.

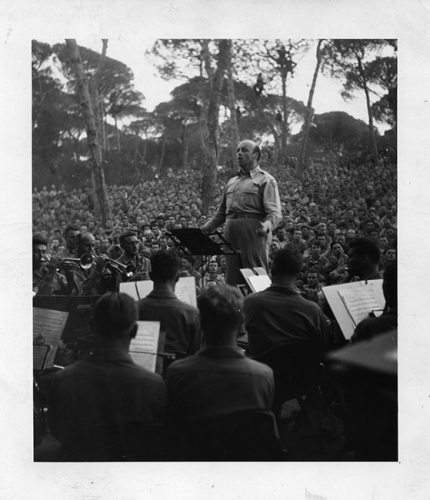

Image courtesy of Lucy Kostelanetz.

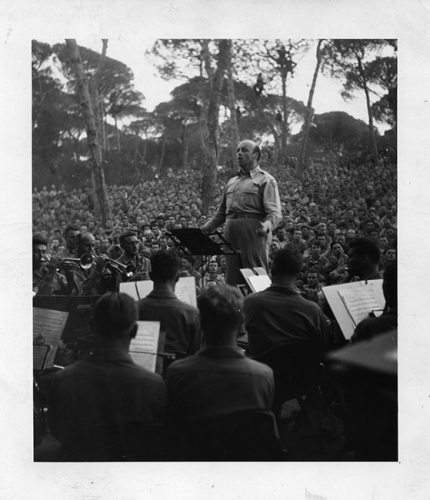

July 1944, Italy: Andre Kostelanetz conducts an orchestral performance for Allied troops less than a year after U.S. troops invaded mainland Italy.

Click to read photo caption. Image courtesy of Lucy Kostelanetz.

Soldiers, chaplains, and medical officers wrote to Futterman, calling classical music a mainstay of their morale. Captain Revel Lahmer told Koussevitzky, who conducted orchestral performances for radio broadcast: “Living in an army camp looking to a future of uncertainty, we need more than words and promises to bolster our morale. We need expressions of strength, health—tangible expressions of belief and faith in living—to make us fight for a future that will be better than any past.” Referring to Koussevitzky’s performance of Roy Harris’s Fifth Symphony, Lahmer wrote: “Please give us a repeat performance … this music expresses [who we are as] Americans. And today more than ever we need the strength that comes through this expression.”

At first Futterman decided which albums to send, but he eventually let enlisted soldiers make selections. “To his surprise,” Fauser says, “they chose a collection of heavies, starting with Elisabeth Schumann’s recording of Bach’s ‘Bist du bei mir,’ Edward Elgar’s Enigma Variations, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, and Richard Strauss’s Rosenkavalier waltzes.” Germans all.

Also, Fauser discovered that soldiers loved Richard Wagner, arguably the epitome of German music and Adolf Hitler’s preferred composer.

“Soldiers were actually listening to Wagner quite a bit but not in the same way you see in that helicopter scene in Apocalypse Now with Wagner’s ‘Ride of the Valkyries,’” Fauser says. “They used it for recreation and uplift.” They often listened to it in groups at their camps, not while taking a hill or shooting down enemy aircraft.

One soldier wrote home: “It doesn’t make any difference what composers’ music is played. We are not fighting individuals, nor are we fighting against the products of the culture of our enemies. Beautiful music should be regarded and cherished for what it is—just beautiful music. If it is written by an enemy sympathizer that is unfortunate. But if it is good music it will live and be loved long after our hates have become a thing of the past.”

Fauser found that Futterman’s work inspired formal listening sessions, sometimes in chapels. Soldiers would sit in rows, as if in a concert hall, and face the music—a hand-cranked phonograph under candlelight. “You could argue that soldiers were so ready for any kind of entertainment that they’d have listened to anything,” Fauser says. “But letters home tell another story. The soldiers clamored for more classical music.”

In a letter to radio journalist and composer Deems Taylor, an anonymous soldier wrote: “I know that I express the feelings of thousands who perhaps don’t have the time to sit down and write to you. We who are busy seven days a week training and fighting for our ultimate victory want and need good music. We need it because it clears our minds and gives us relaxation; we need it because it gives us purpose, courage, and hope in the cause for which we are fighting.”

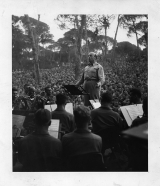

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

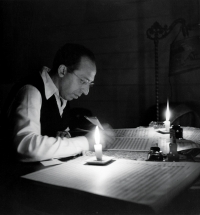

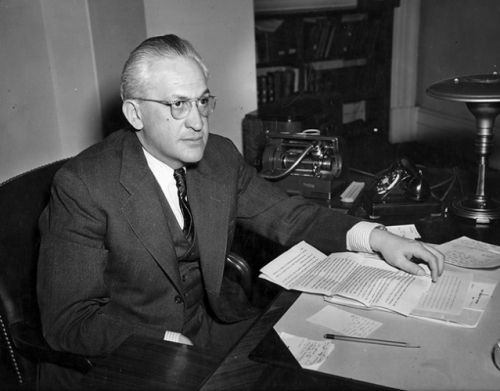

Harold Spivacke directed the Library of Congress's Music Division and fulfilled a unique role in the war effort, including making sure soldiers received libraries of albums. To his surprise, soldiers clamored for classical music.

Click to read photo caption. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Futterman worked with Harold Spivacke, the director of the Library of Congress’s Music Division, to make sure that crates of records found their way onto submarines in the Atlantic and aircraft carriers in the Pacific, into army hospitals in the Philippines and training camps in Alaska.

Spivacke was involved because he was chairman of the Sub-Committee on Music of the Joint Army and Navy Commission on Welfare and Recreation. The chairmanship was not a typical librarian duty, but Spivacke was not a typical librarian.

Before Pearl Harbor, the Library of Congress’s Music Division was like any other library department: interested in collections and acquisitions. But after the United States declared war, Fauser says, “the division became the hub of all wartime music endeavors, and Spivacke served as the mediator between the military and the country’s musical community.”

The U.S. Marine Corps came to Spivacke to borrow two reel-to-reel tape-recording machines to train soldiers to identify enemy planes and artillery. Spivacke gladly lent the machines, Fauser says, and then never saw them again.

Spivacke created the Army Song Leader program and the Army Hit Kit, pamphlets of songs that were mailed to soldiers so they could sing popular songs in groups. The idea, Fauser says, is that the army preferred singing soldiers to idle ones. “The employment of music by the German Army has received considerable publicity as part of its daily routine,” wrote Major Howard Bronson, who worked with Spivacke. “Thus if mass singing worked for Germans, maybe it might also benefit the American Army.”

Spivacke and Bronson also created a music advisor program that recruited musicians, performers, and composers for army duty. Fauser says that the advisors were in charge of musical activities wherever the army assigned them with the purpose of using music as a psychological weapon to win the war. Composers William Schuman and Blitzstein joined. So did band leaders Glenn Miller, Wayne King, and Joe Jordan.

In the Library of Congress archives, Fauser found a letter in which Copland explains to Schuman why he was reluctant to enlist: “I hate like hell the idea of giving up composing at least until New York is under attack.” (See “Captain Copland?” at left.)

Copland never enlisted. In 1943, as men in their forties were being drafted, he was designated 3-A—ineligible for the draft because his mother was dependent on him. But he made his mark with several compositions that supported the Allied cause.

Still, at the onset of war some people were worried that composers would have little place in the war effort or would need to contribute in other ways.

Fauser found some documents from two musical administrators—Ross Lee Finney at Smith College and Claire Reis at the League of Composers—who sent questionnaires to composers to find out what they thought their function should be during the war. Some responded that they had little to offer. Others, such as Earl Robinson, said that “songs can be bullets.” That is, propaganda. Composer Marion Bauer’s response was pragmatic: her colleagues should “compose works that would be timely, principally choral numbers” that might be used for concerts throughout the country. During those concerts, the U.S. Department of the Treasury could sell war bonds.

Reis wanted to know composers’ individual abilities in case they were drafted. She asked if they could teach an instrument. Most composers, including Elliot Carter, Nathaniel Dett, Ernst Krenek, Richard Rodgers, William Schuman, William Grant Still, Barber, Copland, Cage, and Gould, said they could not. Only William Handy, Werner Janssen, and Robinson said they could. Cowell admitted, “Not too well.” Arnold Schoenberg answered, “I guess.” And so, Fauser says, Reis’s goal of creating a national talent pool was unsuccessful.

Composers did what they did best: they wrote music. And they had the support of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who said composers and musicians should continue making music because it was “one of the finest flowerings of that free civilization which has come down to us from our liberty-loving forefathers,” and that music was “a force of morale.”

Image courtesy of Lucy Kostelanetz.

In Cologne, Germany, Kostelanetz and Pons posed in front of a burnt-out German tank and the Cathedral of Cologne, one of the few structures left standing after the Allies bombed the city.

Click to read photo caption. Image courtesy of Lucy Kostelanetz.

But composers didn’t wait to be told what sorts of music to make or which songs to conduct. The Juilliard School’s Ernest Hutchenson held victory concerts at the Metropolitan Museum, with famous musicians such as Marian Anderson, Vladimir Horowitz, Lotte Lehmann, Yehudi Menuhin, and Arturo Toscanini drawing big audiences. In January 1943, the fiftieth performance was attended by nineteen hundred people—double the capacity of the Met’s auditorium. These musicians, in turn, helped the government sell war bonds. Fauser found a photo of Pons selling bonds at the Met two months after the United States entered the war.

Hutchenson said that the purpose of the concert series was “to meet evil with superior morale.”

Koussevitzky said that musicians and composers had to focus on putting “better music than ever within the reach of the multitudes who will need its divine solace in grave days to come.” American musicians had to become “the new bards, new Orpheuses—inspiring, invigorating, ennobling, and consoling.”

Image courtesy of Lucy Kostelanetz.

February 1945, Burma: U.S. Air Force Major General Howard Davidson greets Pons and Kostelanetz, who had flown in after concerts in China and India.

Click to read photo caption. Image courtesy of Lucy Kostelanetz.

Andre Kostelanetz was the first to respond to the call. He commissioned a series of musical portraits of famous Americans just eleven days after Pearl Harbor. Kostelanetz said his series was “a reaffirmation of the democracy in which we live and the people who have made our country great.” Copland met the challenge with Lincoln Portrait. Jerome Kern composed Mark Twain, A Portrait for Orchestra. And composer Virgil Thompson used New York mayor Fiorello LaGuardia and the writer Dorothy Thompson as inspiration for musical portraits.

Others took a more propagandistic approach. Barber, for instance, composed the distinctly militaristic “Commando March” for military bands while serving in the air force. But Fauser found that Barber, because of his military duties, had little time to compose other works until he gained a different assignment. The same was true of Lehman Engel, who was put in charge of a sixty-eight-piece band at the Great Lakes Naval Station near Chicago. Engel was later promoted to lieutenant and led the music division of the navy’s Photographic Science Laboratory, where he helped produce propaganda films.

Engel was one of several composers and conductors who led bands that sprouted up during the war. Some were stationed stateside. Some wound up touring with the USO. All were grateful for work. “The war was a boon for rank-and-file musical professionals who suffered through the Great Depression,” Fauser says. In the Library of Congress archives, she found that over 95 percent of all USO performers were little-known musicians, thankful for jobs in music. And servicemen, in turn, were thankful for the music—especially classical.

Soldiers at Fort Monmouth in northern New Jersey sent telegrams to the army’s Special Services Division requesting that it cancel a theater show to make room for classical pianist Vladimir Horowitz.

Abroad, the USO took classical music to war zones even though at first, Fauser found, the organization doubted soldiers would appreciate orchestral arrangements and arias. She found a memo to Colonel Marvin Young in the Special Services Division: “With the exception of Marian Anderson, Jascha Heifetz, and people of that caliber, I do not recommend offering concert people to posts. Women might be more acceptable (because they are women), but men would not be wanted.”

Young disagreed and pushed for the classical artists to entertain troops. Fauser found that some military companies contacted classical performers directly because the USO couldn’t keep up with demand.

By 1943, performing classical music at military bases became a badge of honor for musicians, Fauser says. Letters home and to the USO show that troops were attending concerts because they loved the music, not just because there was little else to do. As one seaman said about violinist Yehudi Menuhin: “Jeez! That guy can do more with a G-String than Gypsy Rose Lee!”

Menuhin was twenty-seven years old. He could’ve enlisted but didn’t. He could’ve been drafted but wasn’t. His personal guilt, Fauser says, may have contributed to his extreme schedule. When not performing for the USO, Menuhin scheduled independent concerts near the front lines. In a letter to his father, Menuhin wrote that playing for soldiers allowed him to know his “American brothers” and his own generation in a way that previously hadn’t been possible. Fauser says, “It was a poignant remark for a Jewish musician and former child prodigy long cloistered within a virtuoso career.”

Image courtesy of Lucy Kostelanetz.

In India, Andre Kostelanetz and Lily Pons pause for a photo with part of their orchestra. During their India tour, the couple took the Bengal-Assam Railroad through jungle areas to reach troops.

Click to read photo caption. Image courtesy of Lucy Kostelanetz.

There were many tireless USO performers, Fauser says, but few traveled longer or performed harder than Kostelanetz and Pons. The couple gave concerts for an estimated two million GIs, including a Christmas Eve concert in India. They played in Burma, North Africa, France, Germany, China, and Italy. In Iran they performed for Soviet soldiers.

Pons, used to performing in grand halls for society’s upper crust, wasn’t sure how troops would respond to her. In a letter to a friend, Pons wrote that she was surprised that “these vast audiences of [soldiers], many of whom have never listened to a coloratura soprano, sit so intently and reverently as I sing.”

Kostelanetz’s assistant conductor, Lieutenant Don Taylor, was a pilot with more than three hundred combat hours. Their orchestra was full of pilots, navigators, and gunners, Fauser says. They stashed their upright piano in a military plane’s bomb bay when traveling from war zone to war zone.

Fauser says that for weeks on end, the couple put on concerts every day in unforgiving climates. “And that took a toll on the forty-six-year-old diva,” Fauser says. “She prided herself on performing to the same standards for soldiers as she would at Carnegie Hall.”

They did this, according to Fauser’s findings, because they loved the troops nearly as much as they hated the Nazis.

In a letter from Kostelanetz to a friend, the conductor wrote that upon crossing into Germany on the heels of invading American troops, Pons leaned out of her car and spat on the ground as if the Nazis had infected it with evil. And Kostelanetz wrote, “Now that we are deep in Germany, we are even more pleased with the devastation—most cities are level with the ground or at least not habitable.”

Fauser says, “Not even glamorous sopranos and orchestra conductors were immune to military triumphalism.”

There’s no veiling the fact that Pons and Kostelanetz loved the adoration of entertainment-starved soldiers. But Fauser says that their deep desire to serve the war effort played a far greater role in their motives.

After reading letters, USO reports, and personal travel logs, Fauser is convinced that Kostelanetz—too old to enlist or get drafted—considered his USO touring a substitute for combat duty. He said he was in awe of his audience decked out in battle regalia. In a letter to his orchestra, Kostelanetz wrote: “Anyone who sees and hears the rapt attention and wild enthusiasm of our audiences will realize what music means to our fighting men.”