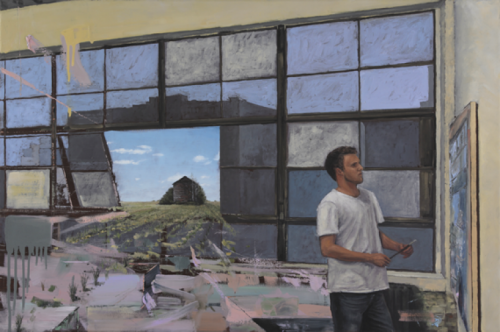

Three o’clock in the morning. It’s quiet and there’s no one around. A dim light emanates from beneath the studio door. Inside, among scattered books and photos, Damian Stamer puts the finishing touches on a painting titled Matinee, in which a remnant of a barn appears through a mysterious portal.

Stamer’s first solo art show in Manhattan is three weeks away at the popular Freight + Volume gallery. He’ll show 14 pieces. He still needs to finish two. Luckily, he doesn’t mind painting through the night. He actually prefers it.

Stamer, an MFA student at Carolina, spends a lot of time in rural Durham County, where as a kid he used to tromp through forests and farms, tinkering with rusted-out equipment and exploring abandoned barns with his twin brother.

He snaps hundreds of photos, looking for something visually striking or nostalgic. “I never know what I’ll use until I get back to the studio,” he says.

The photos are for inspiration. Stamer studies them, and then picks one—a hay bale, a tobacco shack. He dons headphones, puts a few songs on repeat, and then, trusting his experience and knowledge of technique, he paints.

“I think I make my best work when I’m not really thinking at all,” Stamer says. “It may sound odd, but I think it’s like an athlete being in the zone.”

Stamer uses oil paints but experiments with other media, such as charcoal and graphite, to help him produce textures and visuals. “I’m always looking for new tools and ways to spread paint,” he says. “I’ve used masking tape, squeegees, heavy-duty paper towels, solvents, and even a frying pan to splatter paint.”

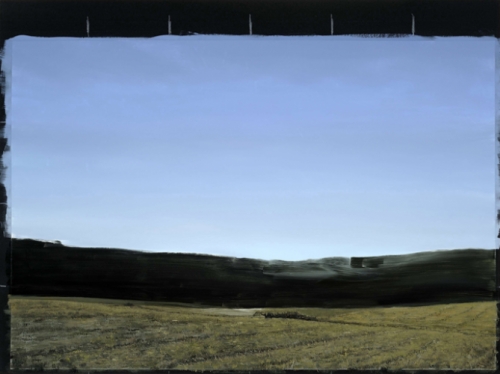

Stamer approaches each painting differently, but each one includes at least one realistic depiction of the Durham County landscape and layers of abstraction to create tension. “Especially with landscapes, you can create this depth,” he says. “It comes out and pops toward you.”

Or, in the case of Red State, red splotches frame the landscape, pushing it back as if seen through a window. Red State is the most obvious case, but each painting is like a window into the past.

A product of the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, Stamer drew inspiration as a youth from contemporary painters such as Robert Rauschenberg. “I was drawn to his combination of abstract and realistic imagery, and how a brushstroke or drip of paint could have as much visual power as an image of JFK,” Stamer says. “Rauschenberg had an amazing compositional touch, and his images never seemed forced or overworked.”

Stamer’s high-school thesis was a series of family portraits with abstract backgrounds, and he continued to combine abstracts with painted depictions of real objects during his undergraduate work at Arizona State and later at two European art schools. When he returned to the United States in 2008, he decided to take on New York’s art scene.

“I felt overwhelmed at first,” he says. But as Stamer slowly met fellow artists and made friends, he showed them his paintings stacked in the corners of his brother’s New York apartment, which doubled as Stamer’s studio. At a party he met the painter John Newsom, who encouraged Stamer and took an interest in his work. They’d talk for hours about their craft. “John became a mentor,” Stamer says. “He’s the one who introduced me to the gallery.”

Freight + Volume liked Stamer’s work. They displayed select pieces and eventually took him on as a featured artist, promoting his paintings at galleries around the country and promising him a show. In the summer of 2011, around the time Stamer decided to seek a master’s degree from Carolina, the gallery made good on its promise. Stamer’s first solo show was set for spring 2012.

For MFA students, a solo show in New York is highly coveted and rare. But instead of pumping out pieces for the gallery, Stamer gave his full attention to school requirements. “I love academia,” he says. “It’s nice to have an intense program where people are invested in your work. They get to know it so well. It’s a good time for growth.”

In the program’s first semester, professors encourage students to experiment. Stamer enjoyed stretching his imagination, but by the end of the semester he didn’t think his finished products were up to snuff. “There were things to be taken from that work,” he says, “but those paintings weren’t how I wanted to present myself in my first show in New York. So I got really busy over break.”

Stamer does his best work when Hanes Art Center has emptied. Sometimes he’ll paint through the night. “I like when it’s quiet and no one’s around,” he says.

From December 2011 through March 2012, Stamer painted six pieces for Freight + Volume. He also finished two others he’d started in the fall. To round out the gallery collection, he added six older paintings.

On April 12, his work complete, Stamer is at Freight + Volume in the heart of Chelsea’s art district. He can finally breathe as aficionados admire a show he’s titled Southern Comfort. As prospective buyers bend his ear over cocktails, Stamer feels as if he’s at the beginning of something special rather than at the end of years of hard work.

“I think I’m homing in on some interesting ideas,” he says, “and I think the work is getting to a compelling place. But it’s dangerous to think you’re producing great work, because then you won’t push yourself to the next level. It’s good to never be fully balanced.”

Regarding the show itself, Stamer says, “I think the verdict is still out. I’m happy with the way things have gone, but I’m waiting to see if other critical voices weigh in.”

Waiting and working.

On a sunny April day, Stamer’s back exploring his old haunts north of Durham. He happens upon an abandoned cabin; he saw it 15 years earlier with his twin brother.

He grips his camera, eyes the old home, and snaps photos. Stamer spends the rest of the day exploring the farms and forests of his youth. He takes his time. No need to rush.

“There’s enough material here to keep fueling this investigation for a long time,” he says.

A day later he’s back in his studio. Tubes of paint cover tabletops. Photos strewn about. Stacks of books. Stacks of canvases.

Everyone is gone and the hour is getting late. Damian Stamer is done studying yesterday’s photos. It’s time to paint.

Damian Stamer is an MFA student in the College of Arts and Sciences. His show at Freight + Volume ran from April 12 through May 19, 2012. Stamer studied at the Stuttgart State Academy of Art and Design in Germany on a Rotary Foundation Ambassadorial Scholarship, and after his BFA he received a Fulbright grant to attend the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest.