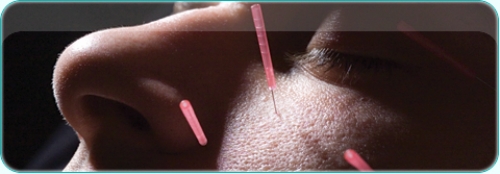

Afraid of needles? Imagine instead a whisker-thin needle so flexible that you could bend it until its ends touched. Then forget that needles are even in the room. Imagine yourself in a state of complete relaxation. Now breathe. Fall asleep. Wake up, completely relaxed and limber. That wasn’t so bad.

Acupuncture is a mystery in the West because we rely on scientific proof for most things medical. Yet there is little scientific proof that acupuncture relieves pain or cures ailments — either in the West or in China, where it has been used for five thousand years. Still, acupuncture has become popular in mainstream Western culture because it often helps patients, even cures them. Because of this gap, a handful of American medical universities are researching the technique. Carolina doctors not only study it; they use it on patients in the physical medicine and rehabilitation department and at the Family Medicine Center, which is home to several clinical trials that may determine whether acupuncture helps relieve headaches, induces labor in full-term pregnancies, or relieves discomfort from menopausal hot flashes. It has been known to do all of these.

Remy Coeytaux is in charge of the studies. He’s a medical doctor and credentialed medical acupuncturist.

“If acupuncture helps prevent c-sections, which it may well do, that has tremendous public health implications,” Coeytaux says. Cesarean sections are expensive, and medically induced labor increases health risks for mothers. “Most everyone agrees that we’d like to reduce the number of cesarean sections,” Coeytaux says.

Nearly 30 percent of pregnant American women have c-sections for various reasons, including hypertension, swelling in the legs, and an increase in the baby’s heart rate.

“The cure for some serious conditions, such as pre-eclampsia, is to deliver the baby,” Coeytaux says. “C-sections are critically important in some situations, but there is a common belief among doctors, patients, and policy researchers that the national rate of c-sections may be quite a bit higher than necessary.” Part of the reason is that labor is often medically induced soon after a woman reaches her due date, to avoid complications. “The problem is that formal induction of labor with medicines such as pitocin places women at a higher risk of needing a c-section.” There is wide consensus that physicians should use reasonable means to minimize the need for medical induction of labor and to reduce c-sections.

Last year, Coeytaux and Terry Harper, a clinical fellow in obstetrics and gynecology, conducted a preliminary acupuncture study, Acumom I. The study showed that patients who received acupuncture treatment delivered twenty-one hours earlier on average. Acupuncture patients tended to be more likely to labor spontaneously and less likely to deliver by c-section. (Only 17 percent of the women who received acupuncture had a c-section. Of the women who received no acupuncture, 39 percent had a c-section.) But the study had some flaws. There were too few participants — fifty-six. Also, the study enrolled women until the end of their fortieth week of gestation. Health-care providers made the decision to induce during the forty-first week.

“In other studies, more women were allowed to go past the forty-one-week mark in their pregnancies before being induced with medications or delivering via c-section,” Coeytaux says. The study, then, is not definitive, although all results point toward favorable outcomes for acupuncture.

And that’s good enough to proceed with Acumom II, which will enroll 120 women. Coeytaux is seeking funding from the National Institutes of Health for a definitive study — Acumom III — which will enroll one thousand women.

Remy Coeytaux (right) and Wunian Chen are conducting acupuncture clinical trials at the Family Practice Center. Photo: Steve Exum.

The Kissinger effect

Acupuncture (Latin for acus, meaning needle, and pungere, meaning to prick) entered American culture when New York Times reporter James Reston was stricken with appendicitis while following Secretary of State Henry Kissinger around China in 1971. Chinese doctors successfully removed Reston’s appendix, but he complained of pain and nausea during recovery. In came the acupuncturist, whom Reston said relieved his discomfort. In a report sent home, Reston said, “I’ve seen the past and it works!” He wrote a front page story for the Times, but failed to explain exactly what acupuncture is.

Wunien Chen, Coeytaux’s Traditional Chinese Medicine expert, says, “this combination medicine is common in China’s best hospitals. Even if the doctors don’t communicate, the patients might go to both.”

Traditional Chinese Medicine practitioners say acupuncture restores health and well-being by stimulating energy flow, which is generally called Qi (pronounced chee).

In 1999, researchers at the University of California-Irvine and Shanghai Medical University found that needles placed in various points throughout the body trigger the release of endorphins, which have been called natural opiates that relax muscles and dull pain. Acupuncturists go one further. They say that when endorphins are sent across synapses — junctions between cells — the resulting stimulation helps put the body back in its natural, healthy state. The technique, some acupuncturists say, fosters the body’s innate healing responses. It helps stimulate the immune system and carry away dead or damaged blood cells.

Coeytaux adds another layer: “We know that every cell has a little electromagnetic field. If you have millions of these cells in an organ, you get a larger electromagnetic field around the organ — a dynamic field that changes depending on the electrical activity of the organ. How do we know this? We do electrocardiograms. We have an EKG that is well-established in Western medicine and it measures electromagnetic radiation of the heart. We know it’s there. There’s no argument about that. We know this organ is sending out this electromagnetic field. Now what do we do with that information? We use it as diagnostic information. We recognize patterns, and we know that a certain pattern suggests that there is heart damage or that there is a rhythm problem. We learn to read it. We stop short of asking the question, ‘does this electromagnetic radiation have any interaction with the tissues of our body?’ We don’t really ask that question in Western medicine. We consider it a by-product of living. We know it’s there but we don’t ask if it’s involved in health or illness.”

Coeytaux says Western medicine has proven other things. Pumping electromagnetic radiation into the body, for example, affects tissues.

“High doses can be good or bad,” he says. “We know it causes cancer or can help other things. But we don’t think of the fact that electromagnetic radiation produced in our bodies might interact with our health. That’s why I say acupuncture is not incompatible with Western medicine. It’s just that we haven’t asked these questions.”

He says it’s plausible, though not proven, that this electromagnetic radiation, generated by organs throughout our bodies, travels through our tissues, presumably on a path of least resistance like all natural things do.

“Like water down a mountain,” Coeytaux says. Maybe electromagnetic currents pass along nerve passages. Maybe currents travel between connective tissue separating or binding together muscles and organs, or through blood vessels.

Needles, he says, are like metal electrodes. If you put two near each other, an electrical current is measurable.

“Possibly by putting an electrode on that spot, it somehow immediately alters the organ or organs that generate it. I don’t know if that’s true, but it’s not implausible.” Chen calls Coeytaux’s explanation the best he’s ever heard.

Does it work?

Warren Newton, chairman of Carolina’s family medicine department, says, “Some doctors are still skeptical about acupuncture, but I don’t see very much hostility toward Remy’s work. The key issue for me is does acupuncture work?”

Newton says that acupuncture, unlike many alternative approaches, has a well-developed comprehensive diagnostic system. It also has a long track record, which Coeytaux and Chen are continuing at the Family Medicine Center. As Newton notes, they have very loyal patients.

Gary Barker, a fifty-four-year-old Chapel Hill construction worker, is one of them.

“I would wake up with a headache and it would get worse all day,” he says. “By eight o’clock at night, I couldn’t take it any longer and would lie down. That somewhat relieved it. Then I’d go to sleep, and the same thing would happen the next day.”

This went on for eighteen months. Drugs containing codeine dulled the pain for a couple of hours, but taking too much made Barker groggy. The hospital did CAT scans, checked spinal pressure, and prescribed several medications. None worked. Neurologists shot botulin toxin into his head to deaden aggravated nerves and relieve pain. It didn’t work, though he reports a less wrinkled forehead. “I was at the point where I would try anything,” Barker says.

Neurologists explained his choice of referrals: psychiatry or acupuncture. He took the earliest available slot, which happened to be with Dr. Chen. There was no change in his condition after three sessions. Chen told him it takes time. Then, it happened. “I walked out of the fourth session without a headache. I kept thinking it would come back, but it never did. It’s unreal. I’m a believer.”

It’s unclear what caused Barker’s headaches. He takes several medications for a bad heart, some of which cause side effects including headaches. But Barker had taken the meds for a decade before he experienced headaches. Now he receives acupuncture once a week and takes Chinese herbal medicine that, he’s convinced, gives him more energy.

Last October, Coeytaux and a team of six other doctors published a paper in the journal Headache detailing a study of seventy-four chronic daily headache sufferers like Barker. All patients received medical attention. Those who did not receive acupuncture treatments did not see significant improvement, except for “a weak trend of decreased daily pain severity.” Acupuncture recipients, though, reported a significant reduction in headache pain and long-term quality-of-life improvements.

Western medicine breaks down headaches into two major types — tension and migraine. Tension headaches are the common mild-to-medium pain headaches we all know. Migraines are more severe, sudden, and can be triggered by different things, such as certain foods, varying hormone levels, sensitivity to light, and even weather. Though less common, migraines afflict over thirty million Americans.

East meets West

Coeytaux became interested in headaches after seeing too many people receive inadequate medical care for their headaches. He came across acupuncture and was fascinated. He realized that from a public health point of view, doctors should study it. “People are using acupuncture,” he recalls thinking. “Either they’re wasting their money or we’re missing out.”

Coeytaux attended a brief acupuncture training program at UCLA. He loved it, and decided to take two hundred training hours to become a credentialed medical acupuncturist.

Back at Carolina, Coeytaux found the perfect partner in Chen, who was trained in both Eastern and Western medical traditions in China. Their work together has convinced them that combining Eastern and Western medicine in one clinical setting is possible, and perhaps preferable.

For instance, Western medicine has uncovered the pathology of headaches — how they develop and cause pain. Some drugs work. Some don’t. Most have side effects. Eastern medicine offers natural treatment including acupuncture, which is safe and often relieves pain.

Coeytaux and Chen, along with occupational therapist Kate Lindemuth, are now writing a paper about how to combine diagnostic and treatment methods from both traditions most effectively.

And Newton, for his part, is curious to know if clinicians can be trained to do simple acupuncture treatments for sinus inflammation and similar conditions.

“Do you need knowledge of acupuncture points in order for acupuncture to work?” he asks. “Can we teach someone to do this? There are lots of clinical questions like this.”

In the meantime, Coeytaux and Chen are trying to show that both are better. “Since we know both, we should use both,” Chen says.

Coeytaux adds, “Eastern and Western are not like parallel approaches. We’re trying to integrate both perspectives. From a clinical point of view, it’s logical.”