For most of us, the word shaman conjures vague notions of magical witch doctors, mysterious man-animal figures, spell-casters whose dealings with the supernatural make them powerful and dangerous.

Well, they are these things, says Silvia Tomášková, an archaeologist at UNC. But through the centuries, they’ve been quite a bit more than that. Shamans were (and still are in some cultures) healers, litigators, artists, priests, and all-around problem solvers, all rolled into one — real proto-renaissance men. Okay, proto-renaissance men, women, children, and transgender men.

Siberian roots

Anthropologists have long known that shamanism began in Russian Siberia. And although archaeologists are now considering that it may have begun as early as the Paleolithic era — between ten thousand and forty thousand years ago — we know nothing about what those shamans might have been like.

The first real descriptions of shamans were scribbled down by seventeenth-century explorers — mapmakers, of all people. When Catherine the Great decided to establish Russia as a European empire, Tomášková says, she hired a group of German scientists to map it all out for her.

I like to imagine the mapmakers’ surprise when they came across the Tungus people in Siberia. With all their plotting of coastlines and mountain ranges, surely they didn’t expect to come across exotic tribes with cross-dressing magicians and transmogrifying sorcerers. It must have really freaked them out.

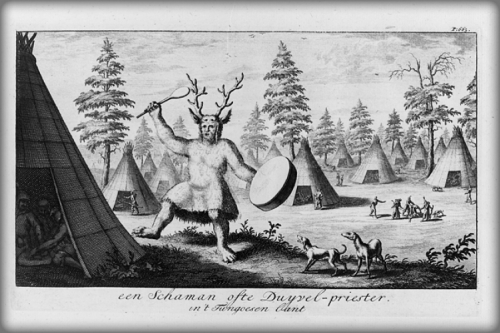

Image courtesy of Bayerische StaatsBibliothek, ©2007 Endeavors magazine.

European travelers to Siberia told of natives with mouths on top of their heads and other monstrosities. Dutchman Nicolas Witsen made this drawing in the seventeenth century of a Tungus schaman, calling him a “priest of the devil.”

Click to read photo caption. Image courtesy of Bayerische StaatsBibliothek, ©2007 Endeavors magazine.

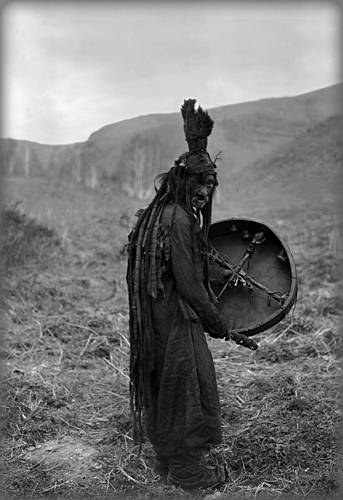

Western outsiders described shamans mainly in terms of their “hocus-pocus tricks,” but that’s putting it lightly. The shamans’ people expected them to physically negotiate with Mother Nature on behalf of the whole community. Shamans controlled the weather, prevented food shortages, found lost objects and animals, and looked into the future. They created fabulous works of art, and helped to solve problems between tribe members. They could transform into any animal at will, and their ceremonial garb often included crowns of antlers and feathers, shoes shaped like hooves, paws, or bird claws. They doctored the sick, and even helped childless women by ascending to heaven to pluck for each of them a soul from the tree of embryos. In short, the shaman was psychopomp extraordinaire.

In their diaries, which anthropologists call “ethnographic records,” the Westerners wrote vivid descriptions of a couple of different ways in which the Siberian peoples chose new shamans. One method called for the tribe members to choose someone based on some sickness, physical mark, or even special powers — these could include predicting the weather, healing animals, and precociously resolving conflicts, Tomášková says.

The other method, while less straightforward, illustrates why no one ever volunteered for the job of shaman. In this process, the spirits selected a new body — usually that of a boy or girl just reaching sexual maturity — to house a dead shaman’s soul. Then the spirits began whispering, calling, and eventually just outright threatening the poor kid. At this point, the fledgling shaman stopped resisting the spirits’ demands, collapsed into hysterics, had visions, and promptly fell asleep for up to nine days. While this may sound like typical teenage behavior, here’s where it gets really dramatic: during the new shaman’s long sleep, the spirits cut him into pieces and counted his bones to make sure his body contained at least one extra.

After this somewhat painful induction, the new shaman was a fast expert in communing with the spirits whenever he wanted, either by acting as a medium and mouthpiece, or by sending his soul from his body directly into the spirit realm. These are talents that made a shaman pretty handy to have around, which is probably why the Tungus people sometimes went so far as to make their shaman the leader of their clan.

Each community supports their shaman financially, the diarists wrote. They bring food, livestock, and whatever little luxuries the shaman requires. Everyone knows that shamans can use their powers for both good and sinister deeds, and so when they’re happy, everyone’s happy.

A rebirth, of sorts

Some male shamans decided they’d be happiest and most powerful if they were actually women — what Tomášková calls transgender shamans. Ethnographic accounts describe “young men” who changed their gender, she says, which most likely means boys as young as twelve years old.

Some shamans dressed as women only on certain occasions. They slipped into women’s garments to perform ceremonies, and afterward, they changed back to their men’s clothes. But others completely changed gender to live their whole lives as women. They wore only women’s clothing, married and lived with other men, changed their voices to talk at a higher pitch, and even altered the language they spoke. (See “Gender Bender Diction,”.)

We don’t know why this change was important to their ceremonies or powers, Tomášková says. But the tribe gratefully respected any decision the shaman made.

Needless to say, the Germans had no idea what to make of the Siberian natives, Tomášková says. To their European eyes, the tribes seemed savage and even satanic at times. Before long, other Westerners trickled into Siberia, including geographers, scientists, and military captives.

“So we have these wonderful written accounts of the bizarre, the savage, the half-human, half-animal kind of people who did all kinds of amazing things,” she says.

And while those early accounts are colorful and spine-tingling — some depict natives with mouths on top of their heads, among other fantastic monstrosities — they tend to be rather preachy and judgmental, and, well, prone to anatomical embellishments, Tomášková says.

Into the East

Fast-forward to the nineteenth century, and Russia roiling with political turmoil. To isolate political trouble-makers (which included a whole lot of lawyers), the Russian government exiled hundreds of its citizens to Siberia to serve out twenty-year sentences.

But although Siberia does have a harsh climate — its northern extremities are rooted fast above the Arctic Circle — it’s not the frozen wasteland people imagine it to be, Tomášková says. Mainly, it’s just huge, spreading all the way from the Ural Mountains to Japan. The government imagined it to be vast and empty, and sent exiles there so they wouldn’t influence or even have contact with other people.

“These exiles were all very educated urban people who realized, ‘I’m here in Siberia, there’s no need for lawyers,’” Tomášková says. “So they learned the language and wrote extensive ethnographic accounts of the people.” Those lawyer-written chronicles are far more scientific, detailed, and useful to anthropologists today than the mapmakers’ diaries, she says, because the writers actually tried to analyze and understand the native Siberian people and their customs.

By this time, travelers had spread word all across Europe “of these wonders of the world, so to speak,” Tomášková says. And people ate it up — they loved the stories because they fit in perfectly with the time’s pop-culture buzz about natural wonders, geniuses with special gifts, exotic native peoples, and feral children raised by animals.

Even today, we’re fascinated by strange or unexplained natural phenomena. And why not? “We live in a hyper-technological, hyper-developed society with all sorts of problems,” Tomášková says. “There’s a great deal of nostalgia for a world that’s simpler, that has answers. And I think to some degree — at least I would like to think — that people feel a little bit guilty about what’s being done to nature.”

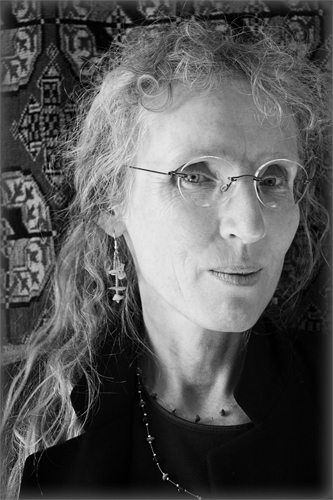

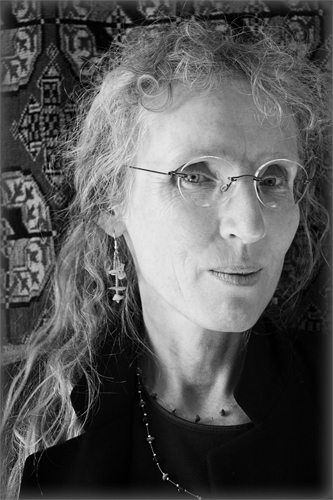

Photo by Jason Smith, ©2007 Endeavors magazine.

Click to read photo caption. Photo by Jason Smith, ©2007 Endeavors magazine.

So the idea of remote societies with appointed liaisons to the earth appeals to a lot of us. And it shows — just pop in at your local bookstore and you’re likely to find shamans in calendars and picture books. They’re still very much in our popular imagination, Tomášková says.

A game of telephone

It’s hard for us to grasp the true essence of what a shaman is and has been, Tomášková says, because we don’t really have any one person in our society who plays all of those different roles. “We tend to think of leaders and healers and priests and doctors as male figures,” she says.

And it comes through loud and clear in the way that anthropology and archaeology texts have evolved over the centuries, Tomášková says; while early accounts frankly recorded the diversity of shamans, most texts from the last two centuries imply that only men were allowed to fill the position.

This game of telephone — of subtly changing stories little by little with each telling — has nudged history slightly off-track. And this version of the story shortchanges both men and women, Tomášková says. “Not only does it take women away from the stage, but it also imposes a very narrow, strict definition of what a man is.”

The big problem with a shifting history, Tomášková says, is that the story of shamanism is bound to the roots of all human culture. If we tell the story to include only men in the shaman’s position of power, she says, we’re as good as saying that this is the natural way of things, that men have dominated all cultures since the dawn of us.

“I think that we’re now in the biological stage of explanation,” Tomášková says. “There’s a gene for everything. If we present the origins of culture this way, what we’re really implying is that it’s biologically in us to be a certain way. And I find that troubling, because it has much greater implications for everything we do.”