It was August 2002, and the First Broad River had turned to puddles. A small pond was all that kept the City of Shelby from running out of water. City manager Grant Goings asked neighboring Kings Mountain for water, but Kings Mountain was already selling all it could spare to Bessemer City.

Goings, though, knew that Bessemer City’s water system was within a few hundred feet of Gastonia’s. So he called up Bessemer City’s manager and asked why they weren’t buying from Gastonia. The answer: Kings Mountain’s water was cheaper.

Goings sighed. He agreed to pay the difference if Bessemer City would connect with Gastonia so Shelby could hook up with Kings Mountain. Shelby hired workers to install temporary water pipes across three miles of countryside to Kings Mountain. Water came rushing to Shelby’s rescue just hours before the faucets would have run dry.

Fast forward five years, when North Carolina was in the grips of another drought. Hardest hit was Rocky Mount, which called on the City of Wilson for aid. The man who answered the call was Wilson’s new city manager—Grant Goings.

“I knew what Rocky Mount was about to go through,” Goings says. Thanks to water from Wilson and timely rain, Rocky Mount was spared.

Goings no longer worries about water supply. Now he worries about water quality.

Runoff from farms and cities is a major reason why some North Carolina waterways are in dire straits. Since the massive fish kills on the Neuse River in the 1990s, regulations have been in place, but are they good enough? Could sewage treatment plants be better? Have farmers improved their fertilizing practices enough?

And what about drought? Why did Rocky Mount nearly run dry, while Wilson was fine? Why did Shelby almost run out of water, while Kings Mountain had plenty to spare?

UNC researchers have been studying drought and problems with water quality, and they have some answers. But will we believe them, and will we act?

Liquid gold

Compared to other states, especially those in the Midwest that suffered through a record drought in 2012, North Carolina has access to a lot of water. Average annual rainfall is higher here than in most states.

“What we lack,” says UNC School of Government professor and water resources expert Richard Whisnant, “is adequate water storage, long-term planning, and legal mechanisms to ensure water rights across a region when the next shortage arrives.”

North Carolina is a typical eastern state with no regional water authorities or enormous reservoirs. Not like in the West, where, out of necessity, water is moved over long distances and must be managed through regional decision-making and long-term planning. Nevada’s southeastern water authority, for example, has a 5-year plan, a 75-year plan, and access to the huge reservoir of Lake Mead.

“They have a portfolio full of potential water sources,” Whisnant says. The authority has even floated the idea of taking water from the Mississippi and piping it across the Rockies to Las Vegas. Crazy as that sounds, it shows how Nevada thinks about water—it’s priceless.

The East’s localized control over smaller sources makes sense when you look at current demographics. But in 75 years? Already we’ve witnessed dozens of cities struggling to find water during droughts, while their neighbors fared just fine. A major reason is that most towns in North Carolina don’t even have reservoirs; they take water from rivers, which are more susceptible to low flows during droughts.

Lauren Patterson, who earned her doctorate from Carolina, researched historical flow rates while a graduate student in Carolina’s geography department and found that from 1930 to 1970, only one area, just northeast of Greensboro, experienced a significant decrease in stream flow. Between 1970 and 2008, though, more than 35 areas from Fayetteville west experienced significant stream flow decreases.

Since 1970, North Carolina’s average annual rainfall has remained the same. But the state’s population has doubled. A lot of that population growth has occurred at the headwaters of rivers. According to UNC environmental engineer Greg Characklis, municipalities have typically based their water needs on the historical record.

“But for some communities, the droughts of 2002 and 2007–08 were worse than anything on record,” Characklis says. “And that raises questions about climate change and whether the historical record is sufficient for planning decisions.”

The latest climate change models suggest that North Carolina will likely experience more periods of severe rain but also more severe droughts. Utility directors acknowledge this, and although most want big reservoirs and better treatment plants, such projects are expensive, take years to complete, and can harm the environment. “So the challenge is to move away from building reservoirs,” Characklis says, “and to do things that are less dependent purely on infrastructure.”

Characklis and his graduate students have been working with Triangle-area utilities on drought management plans, which include stricter conservation, better connectivity between local water systems, and interbasin transfers—taking water from one river basin and using it in a town in a different river basin. All of these strategies have merit, but all are double-edged swords.

Before the 2002 drought, Statesville’s water utility had been selling its citizens and businesses between 5 and 6 million gallons of water a day. During the 2002 drought, those customers reduced their water use to 3.2 million gallons a day. Conservationists applauded. But selling less water means less revenue, which means less money for upgrading water systems and treatment plants.

Your friendly neighbors

Whisnant, who was general counsel for the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources in the 1990s, says conservation isn’t enough, which is why cities struck hard in 2002 spent a lot of money to make sure history never repeats itself.

In 2004, Statesville connected its water system to that of neighboring Salisbury. Other towns, including Cherryville, Concord, Kannapolis, Boone, Mars Hill, and Blowing Rock, spent millions of dollars to connect to neighbors with more stable water sources. Characklis is helping OWASA, Cary, Raleigh, and Durham develop strategies for using regional water supplies to manage drought collectively.

Shelby, though, didn’t connect with Kings Mountain. Instead, Shelby used $1.6 million in state grants, $1.1 million in contributions from the county and its water utility, and about $4 million in loans to build a 13-mile underground water line to the Broad River. In emergencies, Shelby can draw up to 9 million gallons a day from the river.

Why didn’t Shelby connect with Kings Mountain, which has access to a huge reservoir?

“Are you familiar with local rivalries?” asks Rick Howell, who took over as city manager when Grant Goings left for Wilson. “Our city really had to humble itself to ask our neighbor for water in 2002. And Kings Mountain, somewhat reluctantly, was willing to sell us water.”

In the 1970s, Shelby, Kings Mountain, and other municipalities considered jointly building a reservoir, but Shelby thought it didn’t need one. The First Broad River had supplied them just fine for 100 years. After the 2002 drought, Howell was part of a committee that studied how Shelby, Kings Mountain, and three other water utilities could connect water systems. He says town managers and staffs were willing make it work, but politically the idea never got off the ground.

“We’ve left all these decisions up to individual water systems,” says Whisnant, who coauthored a 2010 water allocation report for the N.C. General Assembly’s Environmental Review Commission. A better way, he says, would be to create water authorities that can deal with the needs of an entire river basin.

North Carolina is unique even among eastern states in its reliance on an ancient Roman doctrine called riparian rights: if you live alongside water, you have the right to make reasonable use of that water. In other words, there’s no permit necessary for water withdrawal, not even for a huge power plant or a giant agricultural operation. Whisnant says the doctrine worked well in the past.

“But it’s not a doctrine that deals well with water scarcity,” he says. “It doesn’t sort out who has the right to use water in times of low flows, or when users compete among themselves for water.” It hinders long-term planning. “There’s no way to stop someone from withdrawing water even if we can predict they’ll dry up the stream in 30 years,” he says.

This makes it difficult to manage a watershed. Things get even trickier when a city wants to take water from one river basin and discharge wastewater into another. “We really don’t have a good accounting of how much water is available in our river basins or how much is being used,” Characklis says. “But the state is slowly moving toward this.”

Greenville skims extra water from the Tar River during high-flow periods and pumps excess water into an underground aquifer for later use. Other communities, including some in the sandhills, reinfiltrate storm water runoff into the groundwater. Whisnant says that might be a promising strategy for rural areas where more people get water from private wells. But that groundwater should be tested carefully because storm water and groundwater have problems of their own—some naturally occurring, some man-made, and some animal-made.

What’s in our water?

Arsenic, an extremely toxic chemical that’s been implicated in brain abnormalities, heart disease, and numerous kinds of cancer, has been found in many North Carolina wells.

From 2000 to 2010, more than 65,000 private well owners sent water samples to the state because they suspected something was wrong with their water. Rebecca Fry, from UNC’s Gillings School of Global Public Health, analyzed the test results and found very high levels of arsenic in Stanly, Union, and Rowan counties near Charlotte. “In some cases, the wells had 200 parts per billion,” Fry says.

“We see that in third-world countries.” The FDA says that levels of arsenic under 10 parts per billion are safe. Stanly County health department director Dennis Jenkins says that Fry’s study helped the county get federal funding to extend public water lines to some of the worst-affected areas.

Arsenic is found across the state to varying degrees. Methane isn’t. But soon some residents might want to test wells for the natural gas, as well as certain carcinogenic chemicals, because the N.C. General Assembly lifted the state’s long-standing moratorium on horizontal drilling, the key component to hydraulic fracturing—also known as fracking.

Natural gas, which is mostly composed of methane, is trapped in shale thousands of feet underground. To get at it, companies drill down and sideways and then pump millions of gallons of water and chemicals at high pressure to shatter the shale. The gas is released, piped to the surface, and sold on the open market.

Fracking can and has been done safely, but researchers have found that fracking has led to groundwater contamination in some instances.

A state-appointed commission will draft regulations before gas companies are allowed to drill in North Carolina, but Larry Band, director of UNC’s Institute for the Environment, says writing stiff regulations is one thing and enforcing them is another.

“On other types of environmental laws, such as soil conservation, we haven’t put the resources in place—enough inspectors on the ground—to actually enforce the rules,” Band says.

North Carolina could require gas companies to test wells before drilling begins to show that the water was fine before fracking. “Anything you can do to shift that burden onto the industry is a good thing,” Whisnant says.

Fracking would be limited to central North Carolina. In the rest of the state, many well owners have already been dealing with less-than-ideal water. Bacteria and other pathogens can infiltrate groundwater in the coastal plain, where the water table is very close to the surface. Septic systems, for instance, are sometimes within a couple feet of groundwater.

According to UNC microbiologist Rachel Noble, though, septic systems take up far less land than do landfills, crop farms, animal farms, forests, and urban development. (Read about Bacteria at the Beach.)

All of these spots are rife with nutrients such as nitrogen, which can leach into waterways and play a key role in massive fish kills.

In the past, many people blamed sewage treatment plants for water pollution. Today, utility directors say that wastewater is so highly treated that it’s nearly as good as drinking water was in the 1960s.

“In the Neuse River Basin, that’s pretty close to the truth,” says UNC marine scientist Hans Paerl, who researches the environmental effects of nutrient overloading.

Over the past few decades, regulations have gotten stricter, severely limiting the amount of nitrogen that wastewater plants can discharge. In fact, sewage treatment plants now account for about 20 percent of the nitrogen that enters rivers. Water-quality experts agree that the remaining 80 percent comes mainly from urban and agricultural runoff.

City streets are coated in nitrogen, thanks to exhaust, motor oil, grease, brake fluid, asphalt, concrete, and animal waste. Fertilizer for lawns and golf courses also pollutes streams.

NC State’s Deanna Osmond found that most Raleigh home owners don’t over-fertilize, though a case could be made that any fertilization is too much.

“We don’t really need lawns,” Osmond says. “But we do need to eat.” Farms need fertilizer.

These days, a lot of that fertilizer comes in the form of hog and poultry feces.

The state of waste

Back in the 1990s, poor water quality led to low oxygen levels in the Neuse River Estuary, resulting in massive fish kills and a set of regulations known as the Neuse Buffer Rules. Cities and farms had to reduce nitrogen use by 30 percent, and crop farmers were required to use specific amounts of nitrogen for each crop.

Over the next decade, many farmers stopped growing corn and instead planted cotton and soybeans, which don’t need as much nitrogen. All told, crop farmers reduced their nitrogen use by 42 percent.

After the new rules were put in place, NC State studied 3,000 North Carolina crop farms and found no evidence of over-fertilization. In fact, according to Osmond, most farmers wouldn’t be able to use any less fertilizer without severely risking production come harvest time.

Hog farms also improved, according to Osmond and NC State agricultural extension directors. Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) reduced the amount of nitrogen in swine feed, and that in turn reduced the amount of nitrogen in swine waste.

But that waste. There’s a lot of it. UNC’s Mark Sobsey, a water-quality expert and environmental engineer in the school of public health, calculated that one hog produces about 10 times the waste of a human.

There are more than 9 million hogs in the coastal plain. That’s about 9 New York Cities’ worth of raw sewage sitting in cesspools and getting sprayed onto nearby crop fields. Environmentalists ask, “Would we deal with human excrement this way?”

Cesspools—also known as lagoons—drastically reduce the amount of bacteria in the waste and convert some of the nitrogen into ammonia. The Neuse Buffer Rules now limit the amount of waste farmers can spray and when they can spray it, though farmers can seek permission to spray more, and researchers say the state doesn’t have the resources to make sure all hog farms abide by the rules. (Read The Price of Pork)

One problem, researchers say, is that plants and soil don’t absorb all the nitrogen, ammonia, bacteria, and other pathogens. An NC State study found that only 50 percent of nitrogen from fertilizer is used by plants. Much of the rest leaches into groundwater, which is only a few feet below the surface in much of the coastal plain. And Osmond says that 90 percent of groundwater eventually enters streams.

UNC’s Sobsey has found atypically high levels of antibiotic-resistant E. coli and other bacteria in groundwater and streams near hog farms.

In 2006, NC State researcher JoAnn Burkholder found a major increase since the mid-1990s in the ammonium levels in the Neuse River. In 2009, her lab and collaborators found that a lot of ammonia is moving from groundwater through shallow sandy areas in the Neuse River Basin and into the Neuse River Estuary.

Also in 2009, NC State doctoral candidate Meghan Rothenberger found that certain types of harmful algae have been on the rise in the estuary in response to skyrocketing ammonia concentrations. Her analysis shows that urban runoff and human wastewater were mainly to blame for algal blooms in the upper part of the Neuse River. But swine CAFOs were the prime source in the middle and lower Neuse.

In 2011, UNC’s Hans Paerl published research showing that nitrate levels in the upper Neuse have improved. But, he says, “We’ve more than made up for that by increases in organic nutrient loading in the middle and lower Neuse. By no means have we met the state’s goal of 30 percent nitrogen reduction. At best, we’re holding our own.”

There are still massive fish kills on the Neuse, including an estimated 200 million dead menhaden in 2009.

In October 2012, after another year of thousands of fish dying in the Neuse, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association reported that more than 95 percent of fish kills in North Carolina estuaries are due to low oxygen. The main reason for low oxygen is too much nitrogen in the water system.

Playing chicken

In the 1990s, Paerl and researchers from Duke and NC State worked with the N.C. Coastal Federation to create a natural wetland at North River Farms in Carteret County. Wetlands capture chemical runoff and help filter nutrients before they enter sensitive marine habitats. The ongoing $4.8 million project is funded by the Clean Water Management Trust Fund, which the N.C. General Assembly created in 1996 to prevent or solve water pollution problems.

Paerl says setting aside more land for buffers between farms and rivers helps trap nutrients. So would little dams in ditches and streams. Better crop rotation would use less nitrogen. “The problem,” Paerl says, “is that nobody wants to give up more land for buffer zones and wetlands and crop rotation.”

In fact, more land is going to bigger factory farms, especially poultry CAFOs, which are home to hundreds of millions of chickens in eastern North Carolina.

NC State extension officers who help farmers comply with the latest regulations and research say that poultry operations properly store the litter in huge heaps for no more than 15 days unless they can keep it under a roof. But longtime North Carolina water-quality activists Rick Dove and Larry Baldwin say they have seen the huge heaps uncovered for longer than 15 days. “When it rains, the waste liquefies and flows into the streams,” Dove says.

Even if poultry CAFOs are perfectly managed, chicken litter still poses significant problems, not the least of which is that it’s high in ammonia. Also, chicken waste, which is spread on crop fields, is very high in phosphorus—another nutrient the Neuse River doesn’t need more of. But crops don’t require phosphorus nearly as much as they need nitrogen.

In 2008, the N.C. Department of Agriculture found that 74 percent of soil samples had high or very high phosphorus levels. An NC State study showed that crops in high-phosphorus zones don’t benefit from additional phosphorus. According to UNC-Wilmington limnologist Lawrence Cahoon, it was phosphorus pollution in the Chesapeake Bay that caused Maryland and Delaware to clamp down on poultry operations, forcing chicken companies to look elsewhere. North Carolina is now the number-two chicken producer in the country.

Sanderson Farms, the third largest chicken-processing company in the United States, opened a large slaughterhouse in Kinston in 2010 and soon after proposed building another less than three miles from the City of Wilson.

Sanderson said it would need 500 chicken houses—millions of chickens a year—in Nash and surrounding counties to feed its slaughterhouse. The company planned on piping nutrient-rich wastewater—from the slaughter of chickens—several miles east to spray it on fields near the Toisnot River, which drains into Wilson’s Toisnot Reservoir, part of the Neuse River Basin. The City of Wilson protested and filed a lawsuit.

A Nash County citizens group joined Wilson in opposition, as did Raleigh’s city council. Thirteen of 14 communities and organizations in the Neuse River Compliance Association sent a letter of concern to the state; the lone dissenter was Kinston. Even Wilson’s large pharmaceutical industry, which aims to expand operations, protested to the governor’s office. The fear was that if Sanderson built the plant, then further urban development would be stunted because the Neuse River can sustain only so much pollution.

In November 2012, Wilson got good news: Sanderson had withdrawn its plan, though in a press release the company said it’s still committed to building a slaughterhouse somewhere.

If somewhere means eastern North Carolina, it’s unlikely the state will be prepared.

Steve Wing, a professor in UNC’s school of public health who studies the effects of swine farms on air quality, points out that “the EPA and the state put regulations in place to deal with CAFOs one at a time. But the real problem is the density of the many CAFOs.”

As with drought mitigation, water-quality management is proving to be so geopolitically complex that local governments, state regulators, and even the courts are having trouble sorting it all out.

“Water flow and pollution don’t honor political boundaries,” says Wilson city manager Grant Goings. “A project in eastern North Carolina can have significant impacts in the Triangle and vice versa. We’re making choices, and people don’t understand the permanency of these choices. We aren’t connecting the dots.”

No one is saying that North Carolina should cease all agriculture in the coastal plain. But factory farming is a relatively new phenomenon with a murky environmental track record, one that UNC researchers and colleagues at NC State have documented. Their data show that waterways are under attack and factory farms are largely to blame.

The jury is in. What the judge will do—what the state can do to protect our water—is unclear.

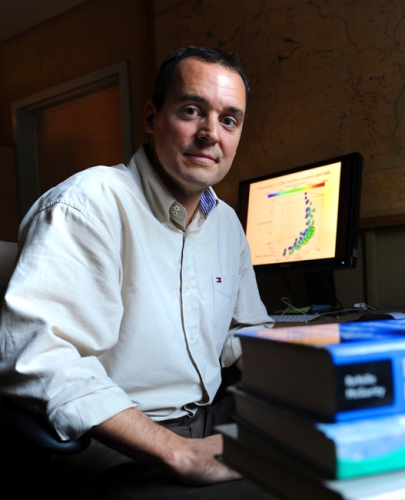

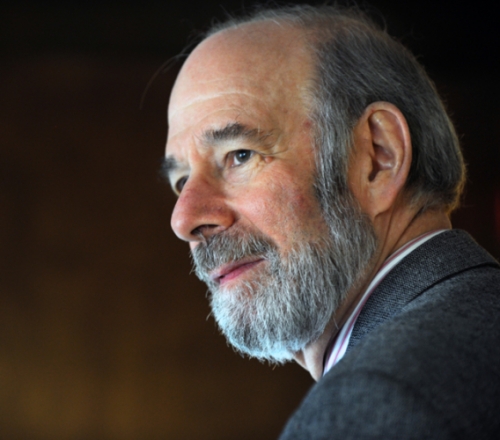

Richard Whisnant is the Gladys Coates Distinguished Professor of Public Law and Policy in the School of Government. Greg Characklis is a professor and Rebecca Fry is an assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering in the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health.

Lauren Patterson earned her doctorate in geography from Carolina in 2011. Larry Band, director of UNC’s Institute for the Environment, is the Voit Gilmore Distinguished Professor of geography in the College of Arts and Sciences. Rachel Noble, the director of the Institute for the Environment Morehead City Field Site, is a professor in the Institute of Marine Sciences, the Institute for the Environment, the Department of Marine Sciences in the College of Arts and Sciences, and the Department of Environmental Science and Engineering.

Hans Paerl is the William R. Kenan Professor in the Department of Marine Sciences, the Institute of Marine Sciences, and the Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering. Mark Sobsey, Director of the Environmental Microbiology Laboratory, is a professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering. Steve Wing is an associate professor of epidemiology in the Gillings School of Global Public Health.

This article first appeared as the cover story for the 2013 January/February issue of The Carolina Alumni Review.