Eric Muller, professor of law, went looking for a little color to enliven constitutional law lectures and wound up writing a book—Free to Die for Their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II. Poring over archival materials about draft resisters from Japanese American internment centers, Muller found a story he couldn’t ignore—a story resonant with themes from his family’s history. (Muller’s family is German Jewish and fled to America only to be classed as enemy aliens when America entered World War II.)

The story on these pages is an excerpt from a lecture that Muller gave on the occasion of receiving the 2000 Philip and Ruth Hettleman Prize for Artistic and Scholarly Achievements by Young Faculty. The lecture was based on his book, which was published by the University of Chicago Press in September 2001.

By January 1944, the United States government had placed almost impossible burdens on its West Coast citizens of Japanese ancestry. In March 1942, in the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the government had first confined them to their homes from dusk to dawn and then rounded them up and warehoused them over the summer in “assembly centers”—filthy sheds hastily thrown up at local fairgrounds and racetracks. That fall, the government shipped them off for indefinite detention behind barbed wire in desolate camps such as the Minidoka Relocation Center in Idaho, the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming, and the Tule Lake Relocation Center in California. Their crime was their ethnicity, and the government made them pay for it with their livelihoods, their possessions, their liberty, and their dignity.

The government demanded still more. In January 1944, it announced that it would begin drafting the very same Japanese American men it was jailing on suspicion of disloyalty. They were to join the same army that had been guarding them for years and that would continue to aim weapons and searchlights at their parents and siblings even if they enlisted.

This extraordinary demand left these young Japanese American men (Nisei) without good choices. On the one hand, they could swallow their outrage at years of mistreatment and leave captivity to fight for someone else’s freedom. To do this would mean more than risking their own lives; it also would mean leaving their families behind to uncertain futures as wards of a hostile government. On the other hand, they could give voice to their outrage and resist the draft. To do this was to risk prosecution, many more years of incarceration, and the lifelong stigma of a felony conviction.

Most of the young men in the camps choked back their resentments and chose to accept the draft as just another unwanted test of their patriotism. Many served bravely in Europe with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the racially segregated battalion that the army created for Japanese Americans. Some lost limbs, others their lives.

Some of the internees refused to comply with their draft orders. More than 300 Nisei from the 10 internment camps refused to show up for induction. They pressed a simple moral question: If we are loyal enough to be in the army, what are we doing behind barbed wire?

Not only did the government decline to answer the question, it punished the resisters for asking it. Through the spring and summer of 1944, agents of the U.S. Marshals Service went to their tar paper barracks and arrested them on charges of draft evasion, carting them off to local jails to await trial. Their cases came to trial in six federal courtrooms across the western United States that summer and fall.

Many of the defendants were at least guardedly optimistic, feeling that if any branch of the federal government might protect them, it would be the judiciary. Although it was wartime, this was not an entirely unrealistic hope. Franklin Delano Roosevelt had had 12 years to load the federal bench with New Deal liberals. Brown v. Board of Education, the most daring defense of individual freedom ever undertaken by any branch of the American government, was just a decade down the road. The federal courts that would hear the prosecutions of the Japanese American draft resisters were in flux, moving from earlier, more timid times on matters of civil rights to the bolder ones that lay ahead.

But the federal justice system failed the resisters dismally in two distinct ways. One was a human failure—a callous refusal of judges and juries to provide the resisters with basic fairness. The other was a failure of law—the troubling inability of even a compassionate and heroic judge to give a persuasive legal account of his moral outrage at the government’s treatment of the resisters.

First, the tale of human failure—the story of the Japanese American draft resisters from the Minidoka Relocation Center in southern Idaho. For a time, it looked as though Minidoka would see no resistance to the draft; events that roiled other camps caused little turmoil at Minidoka.

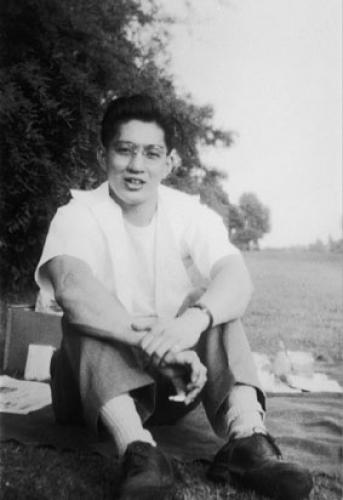

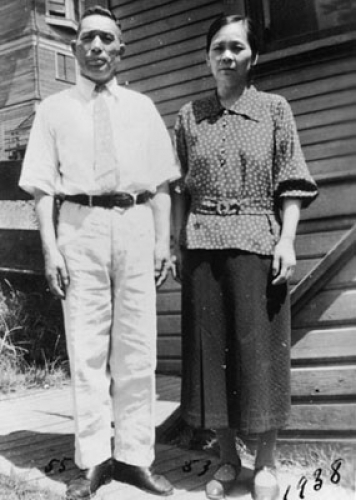

Although tensions had risen at Minidoka by late 1943, reaction to the reopening of the draft in January 1944 was muted. Resentment over the draft smoldered until late April, when six of 57 internees called for induction did not show up. One of the six was Gene Akutsu, the younger son of Kiyonosuke and Nao Akutsu, an Issei (Japanese immigrant) couple from Seattle.

By this point, 18-year-old Gene had been uprooted from his home; lost his chance to attend college; and seen his father seized by the FBI the day after Pearl Harbor and, without formal charges, jailed for two years in a Justice Department camp for enemy aliens. Gene, with his brother and mother, had been held for nearly two years.

Gene reacted with indignation when his induction notice arrived in late April 1944. He felt the government “had been kicking us around a lot,” and he was “not going to stand for that” any longer. When “the day finally came for [me] to go for induction,” Gene recalls, “I just didn’t go.” His mother worried aloud that “we don’t know what is going to happen to you, or whether we’ll ever see you again.”

On April 29, 1944, a deputy U.S. Marshal appeared at the door of the Akutsu family’s barrack with a warrant for Gene’s arrest. He surrendered peacefully and made the three-hour trip to Boise, where the deputy marshal took him to city hall. Gene had no hope of producing the $1,000 bail set by the U.S. commissioner, so the deputy marshal drove him to the Ada County Jail in Boise, where he would await his September trial date.

Minidoka suddenly had a protest on its hands. More Nisei—including Gene’s older brother, Jim—joined the ranks of those refusing to appear for induction. By the end of the summer, 38 Minidokan resisters were sitting in the Ada County Jail awaiting trial.

Finally, on September 6, 1944, they were able to take a walk—a walk under armed guard to federal court, where they were to be arraigned on draft evasion indictments that the grand jury returned that morning. The judge waiting to arraign them, Chase A. Clark, had been appointed less than two years earlier, after losing a bid to be reelected to a second term as governor of Idaho.

As Clark took the bench at the arraignment, the defendants stood before him without counsel. Naturally, they could not afford to hire lawyers, having lost nearly everything when they were uprooted from their homes. Clark’s first job was to find them lawyers—not an easy task in a city as small as Boise. To solve the problem, Clark did something unprecedented: he ordered every available Boise attorney to appear in court that morning. When they arrived, he broke the news that they were each being appointed to represent one or two resisters and that, under prevailing federal court practice at the time, they would not be paid for their service.

Needless to say, the Boise bar was not especially happy with this plan. The problem was not the lack of compensation. The problem was that many of the attorneys wanted no part of the Japanese American defendants. Gene was appointed R.R. Breshears, whom he recalls as large and “stern faced.” After Gene entered his plea of “not guilty,” Clark gave him the opportunity to meet with his attorney to discuss his defense. Breshears told Gene that he was a “damn fool” and then said, “I’ll be damned if I’m going to help you.” Breshears attended later hearings, Gene recalls, but said and did almost nothing.

On September 13, 1944, Clark opened the first trial. The first order of business was a motion by Jim Akutsu to quash the indictment. At the core of his claim was the raw fact of his incarceration behind barbed wire at Minidoka. That fact, he argued, transformed the government’s efforts at drafting him into a violation of both the Constitution’s due process clause and the Selective Service Act. This motion should have presented something of a crisis for Clark because, although new to the bench, he was not at all new to the issue of the incarceration of Japanese Americans at the Minidoka. Indeed, it is not an exaggeration to say that Clark had been partly responsible for the barbed wire fences that imprisoned the internees there.

In April 1942, as governor of Idaho, Clark and the governors of the other western states were invited to meet with federal officials trying to figure out where to move the Japanese Americans of the West Coast. The officials hoped that the western states would agree to welcome the Japanese Americans at loosely structured reception centers, where their fabled Japanese industriousness could be harnessed in the service of the state, the region, the nation, and the war effort. They certainly did not contemplate that the reception centers would look anything like concentration camps.

This was not an acceptable plan to the western governors, and Clark was among the bluntest in saying so. Clark began by confessing that he was “so prejudiced that [my] reasoning might be a little off.” “I don’t trust any of them,” he said, “I don’t know which ones to trust and so therefore I don’t trust any of them.” He then explained that he “would hate it, … after I am dead, to have the people of Idaho hold me responsible … for having led Idaho full of Japanese during my administration.”

Clark made clear that the West Coast states’ Japanese population would be welcome in Idaho only under certain conditions. First, they must arrive and travel in Idaho only under military supervision. Second, he insisted they should be forbidden from buying land in Idaho and forced to return to the West Coast at the war’s end. Finally, and most pointedly, Clark urged that any “Japanese who may be sent [to Idaho] be placed under guard and confined in concentration camps for the safety of our people, our State, and the Japanese themselves.”

All this meant that when he entertained Jim’s motion to dismiss the indictment, Clark was presented with an attack on the constitutionality of the very circumstances of confinement he himself had demanded. Federal law at the time required the disqualification of any judge who had a “‘personal bias or prejudice,’ by reason of which the judge [was] unable to impartially exercise his functions in the particular case.” Jim’s attorney did not move for Clark’s recusal, but sound judicial practice ought to have prompted Clark to remove himself from the case on his own motion. How could he possibly adjudicate the constitutionality of what he himself had demanded? Yet Clark did not recuse himself. He heard the motion and denied it without recorded opinion.

Clark then set in motion what can only be described as an assembly line of federal criminal justice. Over the next 11 days, he opened and concluded 33 separate jury trials—sometimes hearing as many as four trials in a single day. Needless to say, the trials were hardly elaborate. In each case, the government called a witness or two to establish that the defendant was classified 1-A for the draft, was duly called to report for induction, and failed to report. In some cases, an FBI agent offered in evidence a statement the defendant gave upon his arrest, usually expressing anger at the eviction and internment of the West Coast Japanese Americans and a desire to abandon American citizenship and expatriate to Japan. At that, the government rested.

The typical defense case was also quite spare. The extant judicial records suggest that in each trial, the defendant testified as the lone defense witness. The recollections of surviving Minidoka resisters tend to show that even this minimal involvement by counsel was an exaggeration. Gene remembers struggling to mount his own defense while his attorney stood idly at the back of the courtroom. While no transcript exists that captures their exact words in court, it is fair to surmise that most of them said something similar to what one had written to his local draft board:

If I were treated like an American, I would be more than glad to serve in the armed forces but seeing how things are especially since now that I’m put behind barbed wires for no reasons, except that I was born of Japanese parents, I must be a Jap, like the rest of the aliens. In that case I’ll stick to Japan and you can have my U.S. citizenship papers, it’s never done me any good.

Gene’s efforts to explain his reasons for resisting were in vain; Clark instructed the jury to disregard Gene’s testimony regarding his treatment by the government and how it had prompted his resistance. The issue, Clark instructed the jurors, was simply whether or not the defendant had willfully failed to report for induction.

Gene has vivid memories of the jury’s deliberations. “Deliberations” might be too grand a word for the work of these juries, none of which caucused for more than “a few minutes after each case.” He remembers that by the time of his trial, the 23rd, the jury was no longer bothering to deliberate. He remembers that the jurors simply walked out into the hallway for a few moments, long enough for a few drags on a cigarette; said nothing to one another; and returned with a guilty verdict.

Can it really be that the juries in these cases were so cavalier? Are these embittered memories, distorted by the passage of 55 years? There is good reason to believe the former. As it happened, Clark was not the only arbiter in the courtroom who was open to a charge of prejudgment and bias. So too were the jurors.

For the 33 trials, Clark called a total of 34 Idaho citizens to serve as jurors. This meant that when all the trials were completed, each juror had served on at least 10 separate juries. On the seventh day of the trials, a lawyer for one of the defendants challenged the entire venire from which he was expected to pick a jury. He protested to Clark “that members of the jury panel had all sat on juries trying other Nisei on the same charges and thus may not be free of prejudice.” Clark said he would give the matter some thought but the next morning resumed jury selection from the same pool of jurors.

Gene’s recollection that his jurors “deliberated” by stepping into the hallway for a silent smoke may well be correct. Each of his 12 jurors had already heard at least five trials of his fellow resisters; most had heard eight. At that point, what was left to talk about?

Whatever its flaws, this assembly line of jury trials was unquestionably efficient. In the space of 13 days, pausing only on Sundays, the juries convicted the Minidoka internees of draft evasion at an average pace of three per day.

In late September and early October 1944, the convicted draft resisters appeared before Clark for sentencing. Those who had entered guilty pleas and spared the court the (plainly quite minor) inconvenience of a trial received 18-month sentences. Most of the rest were sentenced to terms of three years and three months in prison and a $200 fine.

Immediately after sentencing, the convicted resisters were sent to serve out their sentences at the federal penitentiary at McNeil Island, Washington, an old fortress of a prison that sat on a small island in the Puget Sound about 50 miles southwest of Seattle. As the ferry carried Gene and his fellow resisters across the water toward the prison, he could not help but note the irony that two and one-half years earlier the government had forced them from their homes along the Puget Sound as suspected subversives. Now it was forcing them back as convicted felons.

The Minidoka resisters’ time at McNeil Island passed uneventfully. They shared several large cells in the place they called the Big House—a cavernous and depressing vault of a building with rows of cells stacked upon one another like so many cages.

On December 18, 1944, the Supreme Court held it illegal for the government to continue to detain loyal American citizens of Japanese ancestry, and on January 2, 1945, the military formally reopened the West Coast to loyal Japanese Americans. But the Minidoka resisters continued to sit in the Big House. As the nation celebrated victory over Japan on September 2, 1945, the Minidoka resisters sat in the Big House. On October 28, 1945, Minidoka closed, but its draft resisters still sat in the Big House. There they remained until April 30, 1946, when they were transferred to an adjacent minimum-security prison camp. It was not until April 1947, when they had served well over two-thirds of their sentences, that the Minidoka resisters were paroled.

The trial, conviction, and imprisonment of the Minidoka resisters took a painful episode—their eviction and internment—and made it excruciating. The pain was more than some could bear. When Gene and Jim returned to Seattle in April 1947, they found their parents living in a makeshift hostel. Their father was scrambling to set up a shoe repair business around the corner from where his thriving prewar shop had been. Their mother was a ruined soul. With her family reunited, the stress and trauma of her wartime experiences caught up with her and consumed her. Six months after her boys returned home, she took her own life. She did not live to enjoy even the minor solace of seeing President Truman pardon them on Christmas Eve 1947.

From our perspective 55 years later, it is easy to point the finger of blame for the plight of the Japanese American draft resisters at human beings like Clark and the 34 Idaho jurors who could not find it within themselves to offer these young men a fair trial. But the story is not that simple. The story of the draft resisters from the Tule Lake camp shows an even more difficult aspect of the story of the Japanese American resisters: behind these human failures was a failure of law itself.

Judge Louis Goodman ordinarily heard cases in San Francisco but traveled to the small logging and fishing town of Eureka to hear the cases of the 26 resisters from Tule Lake. Eureka had a long history of anti-Asian prejudice. Had Goodman consulted the Chamber of Commerce’s Guide to Eureka when he arrived, he would have seen on its cover the boast that Humboldt County was the only county in California without a “Chinaman.” It quickly became apparent to Goodman that the townspeople of Eureka were prepared for not so much a trial as a judicial lynching.

Goodman saw the case against the resisters very differently from Clark, and he was prepared to hand the government a defeat. He and his law clerk were, however, concerned that “something terrible might take place” if he ruled in the defendants’ favor because “there was such terrible prejudice in the community.” Indeed, they were a bit frightened for their own safety—scared that “they might be lynched.”

As a result, Goodman left the resolution of the Tule Lake resisters’ case to the very last minute of his week in Eureka— a special Saturday morning session. He and his law clerk toiled late into Friday night, struggling to produce an opinion that would support dismissal of the government’s charges. The dearth of legal research materials in Eureka did not make it easy. By Saturday morning, they had managed to cobble together an opinion dismissing the charges on due process grounds. Goodman read it from the bench as a car idled outside the courthouse, ready to take him and his clerk back to San Francisco.

The heart of Goodman’s opinion was his holding that the prosecution of the Tule Lake resisters violated their right to due process of law. He stated and justified that holding in just a few sentences:

The issue raised by this motion must be resolved in the light of the traditional and historic Anglo-American approach to the time-honored doctrine of “due process.” It must not give way to overzealousness in an attempt to reach, via the criminal process, those whom we may regard as undesirable citizens. It is shocking to the conscience that an American citizen be confined on the ground of disloyalty, and then, while so under duress and restraint, be compelled to serve in the armed forces, or be prosecuted for not yielding to such compulsion.

That was it. The prosecution of the Tule Lake resisters ran afoul of due process because it “shocked” Goodman’s “conscience.”

When Goodman finished reading his opinion, the courtroom fell silent. As you can imagine, the prosecutor was quite unhappy with the outcome. In a letter to his superiors at the Department of Justice written later that day, he confided that “Judge Goodman’s reasoning, together with his opinion, have never coincided with my idea of what the law on the subject should be. As a matter of fact, I have great difficulty in reconciling Judge Goodman’s opinion with any principles of law I am familiar with.”

This reaction was more than just sour grapes. As an application of settled legal doctrine, Goodman’s opinion was decidedly weak. By invoking this “shocks-the-conscience” test for a due process violation, Goodman stepped into an area of pitched legal battle. The Fifth Amendment’s due process clause forbids the federal government from taking away a person’s liberty without due process of law. As might be imagined, the core concern of due process has always been process—the mechanisms by which government deals with and especially imposes deprivations on its citizens.

By 1944 it was well settled that due process requires government to give various sorts of procedural safeguards before subjecting people to certain kinds of deprivations. A government that wishes to punish people for smoking pipes must first publicly announce that pipe smoking is illegal; a government that wishes to enjoin a landowner from making some noxious use of his property must give him an opportunity to be heard on the question before the injunction takes final effect.

Somewhat oxymoronically, the Court has held that due process is also concerned with substance. That is, the due process clause guarantees more than just process: it also makes it impossible for government to subject people to certain sorts of deprivations, no matter how much it first offers in the way of procedural safeguards. For example, a government cannot authorize the cutting off of a batterer’s hands as a remedy for the tort of battery, even if it offers the batterer all the procedural protections known to our legal system. This remedy would violate the batterer’s right to substantive due process. It would strip him of a fundamental freedom to bodily integrity, a basic “liberty” of the kind mentioned in the due process clause.

The trouble with this branch of due process doctrine is that the due process clause says nothing about chopping off hands, nothing even of “bodily integrity”; all it speaks of is “liberty.” It is up to judges to determine the scope of the word “liberty” and to say what it encompasses. This doctrine has brought the federal courts some of their most agonizing modern debates—is a woman’s decision to terminate a pregnancy or the wish of a terminally ill patient to seek life-ending drugs a “liberty” insulated by the due process clause from government interference?

We are familiar with these substantive due process battlegrounds, but in the 1940s, the Court was beginning debate on a slightly different question of substantive due process—whether the due process clause authorized judges to review criminal convictions for conformity with loosely defined notions of “fundamental fairness.”

This dispute was not merely an arcane disagreement about the meaning of the word “liberty” in the Fifth Amendment. It was a dispute about the proper role and power of judges. Justice Hugo Black complained that a judicial inquiry into the “fundamental fairness” of a criminal trial was too loose, open-ended, and dependent upon the personal preferences of the judge making the assessment. Justice Felix Frankfurter defended the “fundamental fairness” method against Black’s attack, contending that this form of review, while open-ended, still needed to comply with “accepted notions of justice.”

It was into this doctrinal maelstrom that Goodman plunged when he dismissed the indictments of the Tule Lake resisters on the basis that they were “shocking to his conscience.” He did not support his holding with citations to any relevant precedent—an omission due primarily to Eureka’s lack of legal resources.

Even with access to the finest law library in the country, he would not have found much support for his opinion. The situation in the case of the Tule Lake resisters simply did not lend itself to the due process doctrine Goodman invoked. He did not specify whether it was the government’s decision to draft the interned Nisei or the prosecutor’s decision to indict them for resisting that was shocking to his conscience. Either way, he was pushing due process review into wholly uncharted territory.

Goodman did not maintain that the federal government lacked the raw power to apply the draft laws to American citizens interned on suspicion of disloyalty. He could not have sustained such a view because the federal government certainly has that raw power; indeed, it has the power to draft even resident aliens into its military, and it has done so in every conflict since the Civil War. That greater power to draft resident aliens surely must include the lesser power to draft citizens whose loyalty it doubts.

Of course, to say that the government had the raw power to draft the Tule Lake resisters is not to say that drafting them was wise, kind, considerate, or even fair. The country was at war, and the due process clause offered slim support for the federal judiciary to second-guess the personnel judgments of those responsible for manning the war effort.

Similarly, the Justice Department’s decision to prosecute the Tule Lake resisters for draft evasion—however morally offensive—was probably not meant to be measured against the conscience of a federal judge on a motion to dismiss a criminal indictment. The enforcement of the criminal law is perhaps the most central function of our government’s executive branch, and the judiciary has long recognized that it is ill suited to sit in judgment of the executive’s enforcement decisions.

The prosecutor in the Tule Lake draft cases unquestionably had probable cause to charge the Tule Lake resisters with committing an offense defined by the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940. That decision may have been morally blind to the Nisei’s plight, but it was undoubtedly a judgment for him to make as an official of the executive branch, without regard for the contrary dictates of a federal judge’s conscience.

To be sure, Goodman’s decision in the Tule Lake cases was a courageous one, the only one of its kind among the prosecutions brought against the Nisei draft resisters during 1944. I admire Goodman’s courage. I worry, however, that his opinion is not something we can truly call “law”—an announcement of a principle that might reliably govern any other case. Perhaps these trials from the 1940s ultimately suggest the uncomfortable possibility that law and morality can deviate in difficult cases.

Lest there be any doubt that the law failed even the 26 Japanese American draft resisters who won in Goodman’s court, consider the memories of Tom Noda. He recalls that when Goodman announced his opinion, he and his fellow defendants remained subdued and quiet. There was no emotional outburst—none of the hugging and backslapping that often accompanies courtroom victories in criminal cases. It was not that they were unhappy with the outcome; it was that none of them, in Noda’s words, really “cared whether we went to prison or not because it wouldn’t have made much difference.”

Incarceration was nothing new to these internees. Noda had been behind barbed wire since the spring of 1942 and understood that by beating the draft charges, all he and his fellow internees had won was an automobile ride, under armed federal guard, back to the barbed wire of Tule Lake. This was all the victory that American law would allow its citizens of Japanese ancestry during World War II.

Eric Muller was a faculty contributor for Endeavors.