Laurie McNeil is not your typical physicist, or is she? With her wide smile, bright eyes, and witty personality, this tenured professor of almost 19 years has strong opinions as to why women scientists are not pursuing academics. It starts with an image problem.

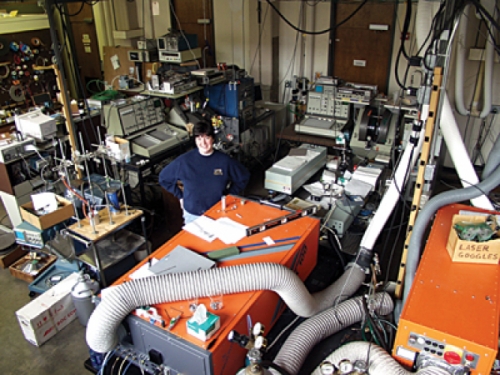

“In this society we don’t have a good image of scientists. We think that science, particularly physics, is done by strange creatures from another planet.” Young women are socialized to value things like close friendships and social causes, she says. “In our society that is viewed to be incompatible with being a scientist. Our stereotype of a scientist is that it’s a man with lousy people skills who just wants to hide in his laboratory all by himself.”

There is a smattering of truth in the stereotype, and it’s no doubt driven in part by the grueling trek to tenure spent writing grants and papers, teaching, conducting research, lecturing nationwide, and attending conferences. But McNeil says that getting tenure is just the beginning of what she describes as the “ethos of research.”

“The whole ethos, in what we call combat physics, is that you are in there slamming away at the universe sixty hours a week, and if you can’t happen to remember your children’s names, well, that’s okay,” McNeil says.

While stereotypes and social conditioning may send the message that women shouldn’t pursue science, seeing few tenured female professors teaching and conducting research sends the message that women don’t pursue science. “It absolutely helps for women to actually see women who are going into academics and making it all work. It’s not enough to simply say, ‘you can do it,’” McNeil says.

Women scientists often cite good mentoring as one reason they chose to pursue an academic career. McNeil, for example, points to Millie Dresselhaus, a world-renowned physicist at MIT. “I worked with Millie for a number of years, and that had a profound influence on my career,” McNeil says. Mentors help solve practical problems in the lab, but they can also help advance the careers of young women scientists by putting their names forward within the scientific community.

But good mentors don’t have to be women, they just have to be good. Marcey Waters, assistant professor of chemistry, completed both her graduate and post graduate work with male advisors and credits them with building her confidence and advancing her career. She notes that she was sure to choose people she felt she could learn from and get along with. “I didn’t just go for the biggest name,” Waters says.

Because mentoring generally takes a back seat to research, it can be difficult to get a predominately male faculty to understand the importance of mentoring young women scientists. “It’s hard to mentor someone who is different from you in significant ways, even if you may want to,” McNeil says. “Some men tend to feel that they came up entirely by their own ability. They didn’t need any help, so why do all these other people need help? In fact they did get lots of help; they just don’t necessarily recognize the forms in which it came. Like simply having people pay attention to you,” McNeil says with a grin.

Of those women who have actually managed to attain tenured faculty positions in the sciences, some send a mixed message — you can do it, but not if you want to have children.

“The reality is that women do confront the biological clock,” says Elga Wasserman, a chemist, lawyer, and author of Door in the Dream: Conversations with Eminent Women in Science. “Women who want to have children have to essentially do it at the same time they are building their career.” Most assistant professors start the five-to-seven-year tenure process in their late twenties to early thirties. Recent studies suggest that women experience a sharp and continual decline in fertility after their early thirties. So a woman who chooses to wait to start a family until after getting tenure can expect to experience at least some difficulty getting pregnant.

Many of Carolina’s tenured male professors have children. The same cannot be said for the tenured women. To Waters, age 32 and with roughly two years remaining before tenure review, it seems clear that the tenure process was designed with another generation in mind.

“It’s a nineteen-fifties sort of set up in my mind. If you think of what’s expected from an assistant professor to get tenure, and the time of life that it occurs, it basically assumes that you have a wife at home who takes care of everything,” Waters says. Today, she says, parents are working. “The system is outdated for everyone since no one has someone at home to take care of things these days.”

To try to accommodate both the tenure clock and the biological clock, many institutions including Carolina have a policy that temporarily stops the tenure clock for one year, theoretically giving women time to have children. But many female assistant professors forgo the extension because they fear that it will be held against them when they do come up for tenure review. “People are going to ask you, ‘so what have you done in six years?’ not five years,” says Silvia Tomaskova, assistant professor of anthropology and director of Carolina’s Women in Science Program.

Finding a place for spouses of women faculty is also an issue, one that Terry Magnuson, chair of genetics and director of the Center for Genome Sciences, cited at a panel discussion sponsored by Women in Science Research.

Traditionally the woman has been expected to relocate when her husband finds a job. But today, the husband must be willing to move and possibly take a less-than-ideal job when his wife lands an academic position. This is particularly difficult when both spouses are scientists and the woman is more heavily recruited.

No doubt it will take aggressive action to increase the number of women scientists who become tenured faculty. According to the National Science Foundation, in 2000 women earned 36 percent of all science and engineering doctorates nationwide, but they made up less than 20 percent of the science and engineering faculty at four-year colleges and universities.

The numbers from individual institutions are similar. At the University of Michigan, in 2001 only 25 percent of tenured and tenure-track faculty were female. At the University of Virginia in that same year, women made up 28.5 percent of the full-time faculty. At Carolina, women made up 34 percent of the full-time faculty.

But the percentages are lower for women scientists at Carolina, who, like their peers nationwide, are primarily in the company of men. The picture at Carolina is changing, though — slowly. In 1991, women made up 18 percent of the tenured or tenure-track faculty in Carolina’s science departments. In 2002, the percentage of women in these departments rose to 24 percent. In certain scientific disciplines the lack of women is more dramatic. Last year in the physical sciences women made up less than 12 percent of the tenured and tenure-track faculty at Carolina.

Carolina hopes to do its part to increase the number of tenured women in science by encouraging graduate students to consider a career in academics and by encouraging women who do choose academics. As a practical concern, Carolina is also concentrating on hiring and retaining more women scientists in tenured faculty positions within science departments. Some departments have implemented a policy of targeting hiring of women scientists with an emphasis on spousal placement.

“This issue will be with us for a while and is of great practical interest to the university,” says Robert Shelton, provost and executive vice chancellor.

Bernadette Gray-Little, executive associate provost, has gathered information about individual departments’ efforts to address the climate for women faculty and will begin assembling a task force to work on the issue more systematically. At Carolina, she says, women are well represented in the sciences among undergraduate, graduate and professional students, and even among postdoctoral fellows, but their representation dwindles at the faculty level. The task force would likely focus on figuring out why.

The Chancellor’s Committee on Appointment, Promotion, and Tenure has made recommendations that would improve flexibility for all faculty, says Barbara Harris, cochair of that committee. Those recommendations are under review.

Steps towards making academics more family friendly are commendable, but they don’t affect women who choose not to have children, and they fail to address the larger and more troubling question — why highly qualified women scientists simply don’t consider academics as a career.

“Maybe it would be possible to move forward if the whole culture were more person friendly, not just family friendly,” McNeil says.

“I think that the focus on children is too much, although it’s a real one, but it should be broadened to include other parts of your life,” Tomaskova says. “Science is just not a culture women want to be a part of.”

Partly to address such concerns, Carolina has instituted the Women in Science Program, now headed by Tomaskova. The program maintains a reading group, sponsors a speaker series featuring distinguished women scientists, and offers undergraduate courses on women in science. Plans include new course offerings, receptions for all new women science faculty, and outreach programs to elementary and middle schools aimed at getting girls interested in science.

As part of her Women in Science course, Tomaskova asked her undergraduate students to interview 15 faculty members, male and female, from four science departments, to explore why science remains primarily a white, male profession. Her students found that women, while successful in their professions, do not typically thrive in the current scientific culture.

“Their impression was that women in the sciences are very driven, very hardworking — much more than they should be — that their lives are not very happy, that they are lonely, and they could definitely use better company than they currently have,” Tomaskova says. But McNeil, who was interviewed for that study, cautions that that perception is not necessarily reality. “I have a pretty happy life,” she says.

Perception aside, the majority of the science faculty members at major research institutions are male. But so what?

Wasserman predicts that if institutions don’t become family friendly, women will go elsewhere, and universities that do not adapt will one day “wake up and see that other institutions have succeeded them, and they have become irrelevant.” The consequences for science may be equally dire.

“You’re neglecting half your talent pool, and science is not going to be the better for it,” McNeil says. “Having women in science is also important for the understanding and appreciation of science. The more that people who do science represent the public at large who pay for science, the more public support science will have,” she says.

Despite the stereotypes, social conditioning, and the apparent incompatibility of tenure and family, some women are making the choice to go into academics — albeit by degrees. Chrystal Bruce, a 27-year-old chemistry graduate student, wife, and mother, has several publications and no less than three grants to her name, as well as a coveted NSF Research Fellowship. Bruce would appear to be the ideal candidate for a tenure-track faculty position at a major research university — but she is not interested. “I know I could do it, I just don’t want to,” Bruce says. Instead, she hopes to obtain a position at a small college, where she can concentrate on guiding undergraduate researchers.

It’s just such highly qualified scientists that Carolina knows it needs to attract. Shelton says, “We are absolutely foolhardy at this institution and any other if we can’t figure out how to attract women.”

Scientists juggle the demands of family and work

There was a time when she almost quit. “I was very stressed,” says Regina Carelli, associate professor of psychology. “I went to my husband and said, ‘I don’t know if I can do this. It’s just too hard.’” Carelli was overwhelmed by being a scientist and a mother and trying to do both well. And she was not alone in that struggle. Of the many successful women scientists interviewed for this article, some had such difficult experiences that they did not want to go on the record. One scientist was so driven to have it all that she was actually in the laboratory when she went into labor. Another was asked if she was going to break the record and return to work after less than two weeks of maternity leave.

The idea that women have to make a choice between a career and children — an idea seemingly outdated — is still present in many academic institutions. The successful women scientists are those who disregard the notion that they have to make a choice, and instead set out to prove that they can have it all. Carelli has two delightful boys, is an accomplished scientist, and just last year received the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers, the highest honor bestowed by the U.S. government on outstanding young scientists.

“Having it all — meaning kids, a husband, a family — does not necessarily mean doing it all,” Carelli says. “It is a full-time job to be a mother and a wife, and then you have a full-time job on top of it. You can’t do everything. That means being willing to ask for help. I am very fortunate because I am married to someone who is very supportive. The traditional roles of a marriage don’t really apply in my household.” She and her husband share the family duties, 50-50, to make it work. The first one home makes dinner; afterwards, she washes the dishes while he gives the boys a bath. “If you both give, then it’s easier,” Carelli says. “It’s never easy, but it’s easier.”

Jenny Ting, professor of microbiology and immunology and a member of the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, agrees that her husband played a big part in her success. “Find the right person. If you’re married to the wrong person, then get a good housekeeper,” Ting says.

Just as important as finding the right partner is finding the right work environment. Ting chose Carolina over equally prestigious, less women-friendly institutions for that very reason. But support does not necessarily have to come from women. Male faculty can be just as helpful. When Linda Dykstra, professor of psychology and dean of the graduate school, was pregnant with her first child, the chair of the psychology department at the time told her he hoped she would take sufficient time off, as he had done with his first child. That kind of support may be most prevalent in departments such as psychology, where women make up a higher percentage of the faculty. Without that support, pressures of taking care of a family while running a lab can cause women to drop out of science.

But the scientific environment may not be solely to blame for the dwindling numbers of women in science. “Part of the blame lies with us,” Ting says. Women tend to doubt their abilities, she adds, and they often don’t even apply for high-profile positions. “We are more cautious, and that sometimes holds us back,” Ting says. “We never think about how good we are.” Even Ting, who has over a hundred publications to her credit, admits she still prepares herself for failure, writing tons of grants in case they all fall through. “We need to have a more positive attitude,” Ting says.

Successful women scientists also possess time-management skills and extreme focus. “You have to be able to multitask — one moment remembering to leave diapers for the baby-sitter, and the next analyzing a DNA fingerprint,” Ting says. Both she and Carelli say that the first thing they learned was to let the small things go. “Something has got to give,” Carelli says. “I was getting my papers out and my grants out, but my house was always a mess.” To have it all, they’ve had to give some things up — such as that second cup of coffee and the paper in the morning, or a chance to speak at some important conferences. They’ve also found some creative ways to get everything done. Ting once brought her five-month-old daughter to a poster session at a scientific meeting.

“This is a great job to be a mom. Sure, I work nine- to ten-hour days and bring stuff home to read,” Ting says. “But I haven’t missed too many of my kids’ events.” She also feels that being a mother has greatly added to her professional life. “As a parent I become a better manager,” she says. “As a manager I become a better parent.” Being a parent has given her a new attitude — wanting to leave this place better than she found it. The desire to contribute to the world is one of the reasons that women go into science, and it is often the same reason that leads them to motherhood.

“For me, it wasn’t a choice — it was never a choice,” Carelli says. “I was going to do both, end of story. I had no idea how I was going to do both, but I was going to, without a doubt.”

Women of Distinction

Here are just a few examples of women scientists at Carolina who have earned high honors in their fields.

American Academy of Microbiology

Janne Cannon, professor of microbiology and immunology

Beverley Errede, professor of biochemistry

Priscilla Wyrick, professor of microbiology and immunology

American Institute of Medical and Biological Engineering

Carol Lucas, professor of biomedical engineering and surgery

Institute of Medicine

Barbara Hulka, William Rand Kenan Jr. professor of epidemiology

Sheila Leatherman, adjunct professor of health policy and administration (Leatherman is now research professor of health policy and administration. — Ed.)

Beverly Mitchell, Wellcome Distinguished professor of medicine

Judith Tintinalli, professor of emergency medicine

Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers

Regina Carelli, associate professor of psychology

Tiffany Heady was a student who formerly contributed to Endeavors.

Marla Vacek is a fifth-year Ph.D. candidate in genetics and molecular biology whose work was recently published in Blood, the journal of the American Society of Hematology. Although she has accepted a Clinical Molecular Genetics postdoctoral fellowship at the National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institutes of Health, she also wants a family someday.