People awakened in the night, five-foot-high water soaking their bed covers. Dogs and chickens perched on rooftops. Bridges washed out, 1,400 roads impassable. This isn’t Katrina. It’s a little closer to home—eastern North Carolina, back in 1999, after Hurricane Floyd.

Fifty-two North Carolinians lost their lives during Floyd, compared to the more than 1,300 Gulf Coast residents who perished during Katrina. Though North Carolina’s flood was on a smaller scale, the disaster cost, and it taught. Can any of the lessons learned from Floyd help us sort through the debris of Katrina? And did Floyd or Katrina help make North Carolina more prepared for its next big storm? We asked these questions of several Carolina scientists. Here’s what they told us.

Just sitting out there

Does North Carolina have vulnerabilities on the scale of the weaknesses in the New Orleans levee system? Yes and no. “It’s basic that coastal North Carolina has a really high probability of being struck by a hurricane,” says Rick Luettich, professor of marine sciences. “We are close to the Gulf Stream, and the Outer Banks stick out from the coast. If you look back over the one hundred twenty-five years that we’ve kept track of where hurricanes strike, if you take all the hurricanes that have impacted the United States’ East and Gulf Coasts, the highest number of hurricanes have visited North Carolina.”

It’s easy to imagine that any high-intensity storm that hits North Carolina might devastate one of your favorite beaches. A draft hazard mitigation plan for Holden Beach, for example, projects that a Category Four or Five hurricane could completely inundate the island and result in catastrophic losses (defined as multiple deaths, complete shutdown of facilities for thirty days or more, and more than 50 percent of property severely damaged).

But New Orleans was a special case—a lot of people living in a low-lying area made to feel secure by a levee system, says David Moreau, professor of city and regional planning and director of North Carolina’s Water Resources Research Institute. “In North Carolina, you’re not going to have a whole city flooded out as was the case in New Orleans. You would not have the sort of massive damage that occurred in New Orleans because when those levees broke, they lost nearly 200,000 houses.”

But Moreau agrees with Luettich that North Carolina’s whole coastline is vulnerable. “The Outer Banks are just sitting there,” Moreau says. “There’s nothing there to protect them from a Category Five storm. Until you move those properties out of that floodplain, you’re going to get flood damage.”

Time for some definitions. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) defines the 100-year floodplain as the area near a river, stream, or waterway that would be covered by water in the event of a 100-year flood. A 100-year flood level is one that, each year, has a 1 percent chance of being equaled or exceeded. A 500-year flood has, each year, only a 0.2 percent chance of occurring.

When Floyd hit, the resulting flooding was estimated to be a 500-year event, Moreau says. Since Floyd, the State Emergency Management Commission, in collaboration with FEMA, has been redrawing the flood maps, incorporating data from Floyd as well as 1996’s Hurricane Fran. Officials estimate that with the revised data, Floyd was probably more like a 150- or 200-year flood event.

In 2000, Peter Elkan, a master’s student in the School of Public Health’s Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering, examined the predictions of 100-year flood elevations before and after Hurricane Fran in 1996 and Hurricane Floyd in 1999. Simply adding those two observations to the historical record that is used to estimate flood probabilities had a significant effect, Moreau says. Elkan found that the data increased 100-year flood levels in the Tar River by 1.8 feet at Louisburg, 5.9 feet at Rocky Mount, and 1 foot at Tarboro. The increase in the Neuse River was 1.4 feet at Goldsboro and 2 feet at Kinston. “These vertical shifts have pronounced effects on the horizon extent of floodplains,” Moreau says. “For example, if the ground slope is one percent away from the river, every foot of increase in elevation would expand the one-hundred-year floodplain by one hundred feet.” In other words, more area is susceptible to flooding.

But flood mapping isn’t precise. “How much flow actually takes place at a five-hundred-year event is a large uncertainty,” says Larry Band, professor of geography. “The oldest river-flow information from North Carolina goes back only to 1895, and only on a couple of rivers. So in trying to estimate the five-hundred-year event, or even the two-hundred-year event, we are extrapolating way beyond what we have data for. Since our best mapping will be only an estimate, we have to be prepared.”

Philip Berke, professor of city and regional planning and faculty fellow at the Center for Urban and Regional Studies, says that preparing for hurricanes means increasing the local commitment to disaster planning. Speaking at a forum on Hurricane Katrina sponsored by UNC-Chapel Hill’s General Alumni Association, he says, “We need to provide stronger incentives for disaster planning. Communities have few incentives to spend on looking ahead and avoiding harm.” He points out that budget cuts have reduced the portion of federal spending used on mitigation (reducing hazards before natural disaster strikes) from 15 percent to only 7.5 percent of total disaster-assistance spending.

Berke also points out that the federal government has a long history of subsidizing development in flood hazard areas through flood insurance, tax write-offs for uninsured losses, beach renourishment programs, and paying for most of the rebuilding of public infrastructure after a disaster. Berke says that this type of risk-sharing creates an attitude of, “We get these disasters, we pay for them with the help of the federal government, so why worry?”

Much of the United States’ flood-control policy has focused on building structures such as floodwalls, dams, and levees, Berke says. “These structural approaches create a false sense of security,” he says. “They make us think, ‘I can build here now; it’s safe.’”

Band points out that in eastern North Carolina, which is extremely flat, even minor structures such as bridges and road crossings can act as “unintentional levees or dams.” “These features can reroute water and cause extensive inundation of the land,” Band says. Better mapping of these seemingly minor man-made features would help the state plan for flood control, he says.

Living in harm’s way

An obvious solution: moving people out of the floodplain. After Floyd, the State of North Carolina did well at providing incentives for people to move out of the most flooded areas, says Jim Fraser, associate research professor in the Department of Geography and a senior research associate at the Center for Urban and Regional Studies. FEMA’s buyout program offers residents money for their floodplain property and then bans any future development there. But FEMA requires that either residents or local governments provide 25 percent of each property’s cost in matching funds. After Floyd, the state knew that most of those flooded couldn’t afford the match and that local governments couldn’t either. So the state provided the full matching amount. “North Carolina is the only state that’s done that,” Fraser says. “It’s probably the most progressive mitigation state in the country.”

But common sense tells you that North Carolina’s floodplains will never be completely free of development. Just take a look at the multimillion dollar homes for sale on the coast, most protected by federally subsidized flood insurance. Then there are the low-lying areas down east that have been settled for centuries—many of them by groups who could afford the land because nobody else wanted it.

Princeville, North Carolina, for example, a tiny town of only about 2,100 residents, is the country’s first town incorporated by former slaves. “People don’t like to talk about it, but for a long time in the South, black folks needed cheap land, and that was in and near the swamps,” says John Cooper, a 2004 graduate of Carolina’s doctoral program in city and regional planning. Prince- ville, for example, flooded at least seven times before Hurricane Floyd. In the 1960s, the town and the Army Corps of Engineers built a levee, which did a good job of protecting against a flood. Until Floyd.

To accommodate a railroad, the Princeville levee included a cutout, which was supposedly on the high end of town. But during the heavy rains after the hurricane, the Tar River breached the cutout, flooding the entire town. No one died, but residents lost homes and pets, and many of the public buildings, including the town hall, were wrecked. And, just as in New Orleans, after the rain stopped, the levee kept the water from flowing back to the river; the town had to pump it out.

After the flood, the Princeville Board of Commissioners voted against accepting a FEMA buyout, electing instead to take federal assistance offered for rebuilding. Many of the residents, most of them elderly, had inherited their land and homes. “They were place bound,” Cooper says. “Their families had been there for over one hundred years. Their ancestors were buried there.”

The Princeville flood made national news because of the town’s significance for African American history, and celebrities such as comedian Tim Reid and musician Prince held benefits or donated money toward its redevelopment. In 1999, Cooper, who was working for North Carolina’s emergency management agency, served as a liaison to then-President Clinton’s Council on the Future of Princeville.

Some of the redevelopment plans have become reality. Princeville’s population is back up to what it was before the flood. Princeville boasts a new school and a new town hall. Residents have moved into new homes and out of the trailers dubbed “FEMAville.” The levee now includes a structure that can be placed over the railroad cutout if the river rises again. But the levee couldn’t be elevated because of the liability it would create for nearby Tarboro, Cooper says. And the old town hall is still gutted. It hasn’t yet been turned into an African American history museum, though construction is slated to begin soon.

“The redevelopment plan was ambitious,” Cooper says. “But once the consulting firm left there was no one left with the technical and management capacity to implement it. So if there has not been the level of recovery that one might expect, I suspect that’s part of the problem.” The position of mayor of Princeville, for example, is a part-time one. When the Princeville redevelopment effort first began, a city manager from Jacksonville was hired temporarily to lead the effort. “So the lesson learned for me is we need to build the capacity of the folks who are left behind to do the work,” Cooper says.

About fifty miles south of Princeville, in Kinston, where more than 450 residents had been evacuated during Floyd, city officials decided to take the FEMA buyout for all those living in the 100-year floodplain. Kinston used some creative solutions such as turning a former high school into apartments for the elderly, creating a pilot program that used prison laborers to build homes on vacant lots, and offering tax credits to a developer to add forty-four new apartments to an existing complex. The city also made plans to turn much of the land abandoned in the buyout into a park with open space, a nature trail, and picnic areas. In the end, more than seven hundred people participated in the buyout.

But the effort wasn’t perfect. Affordable housing is still scarce in Kinston, and the historically black community called “Lincoln City” is gone forever, except for one church and the residents’ memories. And some residents had mixed feelings about the buyout. After Floyd, Fraser and colleagues conducted in-person and telephone interviews with officials and residents in Greenville and Kinston. Seventy percent of the over two hundred residents interviewed said that they felt they had no choice but to sell because the alternatives offered to them weren’t practical or affordable. These mostly low-income residents said they were worried about flooding, but that they worried just as much about not finding affordable housing nearby, losing the support system of their neighbors, moving into a neighborhood where they were unwanted, or having to move too far away from work. Fraser says his study suggests that future buyout efforts should focus more on residents’ concerns and on gaining their trust.

“In many cases, impoverished neighborhoods’ relationships with local governments are already strained,” Fraser says. “It’s not fair to expect these residents to trust the local government to be their advocate. We need to have others involved—people deeply embedded in the community whom the residents can trust.” Members of community-development corporations or other local nonprofits can be effective mediators between local government officials and the residents, Fraser says, but they must thoroughly understand the details of the buyout program so residents don’t get any surprises.

Making sure all residents get the message about disasters and their aftermath is at the heart of a partnership between FEMA, Carolina’s Center for Urban and Regional Studies, and nonprofit organization MDC, Inc. Cooper, now an associate at MDC, manages this demonstration project, which will focus on how to increase disaster preparedness among disadvantaged populations such as the elderly or those with low incomes. The project will include surveys and community forums with residents in or around Hertford County, North Carolina. “When the state emergency management agency puts the order out for folks to evacuate, why don’t people act on that message?” Cooper asks. “Is it the messenger; is it the content; is it the medium? Do we need to find another way to get the message out?

“In New Orleans, the problem was not only lack of preparation on the part of the government but also on the part of the citizens,” Cooper says. “That’s what we’re working on in this project—to find out how you get everyday citizens to be more aware of the potential harm from disasters.”

The rivers recovered—this time

While the losses of lives and houses were most obvious, the hurricanes of 1999—Floyd, Dennis, and Irene—changed North Carolina’s waters, too. Hans Paerl, professor of marine and environmental sciences, and colleagues have monitored waterways such as the Pamlico Sound and published several studies showing ecological changes that resulted from the hurricanes. The massive influx of freshwater from Floyd and Dennis resulted in an increase in low-oxygen water in the sound and many of its tributaries, which led to more disease and fish kills, particularly among shellfish and to a lesser extent among fin fish, Paerl says. And the nutrients in the floodwaters triggered algal blooms, which aren’t seen in the sound in years without hurricanes. “Those effects were most obvious over the first several months after the huge amount of freshwater poured into Pamlico Sound,” Paerl says.

The longer-lasting effects of 1999’s hurricanes—Floyd, Dennis, and Irene— include a change in the composition and amount of algae on the Pamlico and its tributaries. Even that corrected itself after a year or more, Paerl says, but in the meantime fisheries declined. “The change in algae might affect some of the organisms that depend on algae for a food source,” he says. “Some of the fisheries have been off for several years since Floyd, particularly crab fisheries. The sound has more or less come back to normal, but it took several years for it to do so.” North Carolina’s fish are well adapted to the large storms that we frequently get. But the right combination of events could deal our fisheries a blow. The compounding effects of fishing pressure, human nutrient enrichment, and an increase in hurricane frequency and possibly intensity can create a “multiple stressor situation,” Paerl says.

The hurricane-heavy year of 1999 didn’t diminish fisheries permanently. “But looking at the future, if we were to have a large hurricane every year or two years—that could have a cascading effect,” Paerl says. “There’s every reason to be on guard and monitor these systems very carefully, beyond just what happened with Floyd, Dennis, and Irene.”

Paerl and his colleagues do that with two projects that have been emulated by other states: FerryMon and ModMon, in which water-quality monitoring systems are installed on profiling platforms and on the fleet of N.C. Department of Transportation ferries that already travel some of the state’s biggest waterways—the Pamlico Sound and the Neuse Estuary. These projects monitor the impact not only of hurricanes but also of urban, agricultural, and industrial pollution. “It’s important to have a good monitoring program to tease apart the human effects from the climatic effects,” Paerl says. “We can’t manage hurricanes, but we can manage the nutrient load they transport into our coastal and estuarine waters.” So when we do have frequent and large hurricanes, based on monitoring we can more carefully control when we apply fertilizer or when we discharge nutrients into our streams. “It can’t be business as usual if we’ve got thirty years of elevated hurricane activity to worry about,” Paerl says.

Turbocharged weather forecasting

To get out of a storm’s way, you have to know it’s coming. With both Katrina and Floyd, the initial hit of the storm was expected, but it was the hurricane-spawned tornadoes and floodwaters from the resulting rain that caught some people unaware. In New Orleans, that problem was not caused by a breakdown in weather forecasting, but in communications technology, says Daniel Reed, vice chancellor for information technology at Carolina. “After Katrina made landfall in New Orleans, the Doppler radar systems that capture weather data never failed. But the communication network that would get the data from the radar to forecast centers did fail,” he says.

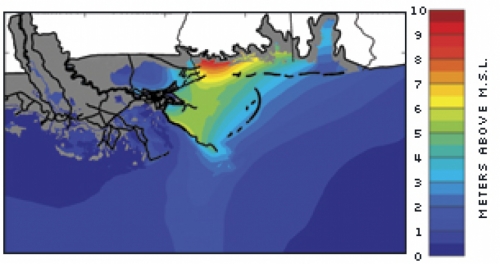

Reed collaborates with scientists nationwide to use the computing resources of Carolina’s Renaissance Computing Institute (RENCI), which Reed directs, to help improve weather forecasting, modeling, and disaster preparation. After Katrina, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) asked marine scientists Rick Luettich and Brian Blanton to use their computer model of water levels and water flow to predict where the toxic floodwaters of New Orleans would go. The waters included paint thinner from flooded garages, gasoline, and other toxic chemicals. “Much of that stuff wound up in Lake Pontchartrain,” Blanton says. “They wanted to know, where in the ocean is it headed?” For their model to be useful to NOAA, Luettich and Blanton needed it to run fast. But they had been running it on a computer system with only sixty-four processors. Reed used his contacts to get some time on a system with over one thousand processors at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications. That meant that Luettich and Blanton could run a simulation of sixty days of floodwater behavior overnight—in about fifteen hours. On their old system it would have taken about ten days to do these runs, Blanton says.

Luettich and Blanton’s model, ADCIRC, uses a grid of tiny imaginary triangles that cover a large part of the western North Atlantic Ocean. Computer code takes current information about winds, coastline, and ocean depths at each of the points of those triangles and uses it to calculate what the water levels will be and where the currents will take that water. The finer the grid they use, the more accurate their model. “If you have a grid where the separation between the lines on the earth is ten miles, then you’re saying that anything in that ten-mile region is going to be exactly the same,” Reed explains. “You know that’s not true. So the finer your grid gets, the more the forecast improves.”

Luettich and Blanton put a package together for NOAA so the agency can do trial runs of the ADCIRC model on its own computers. “They’ll evaluate it, and then if they think it’s a productive product, they will start running it on a consistent basis themselves. Our job is to demonstrate the capability and help enable the transition of the product to the groups at NOAA,” Luettich says. The U.S. Coast Guard has also begun using ADCIRC to predict current patterns for search-and-rescue operations. “If they know where a missing boat started and know what the current patterns were like in the area, they can simulate where the boat might have drifted,” Luettich says.

Luettich’s ten years of work on the ADCIRC model are beginning to pay off; the model produces results accurate enough that it can be used in forecasting. But to do timely forecasts, they need fast computers. Reed and colleagues are installing a new computing system at Carolina that will be fast enough for Luettich and Blanton to run their models at home. The system should be up and running by January 2006. “It’s the most powerful computing system that the state of North Carolina has ever had. It will make some of these complex models possible to run at a rate so that we can actually do planning, not just nationally, but also for North Carolina weather,” Reed says.

Computing power can also speed up relief efforts after a storm. Reed points out that another problem in New Orleans after Katrina was the failure of the city’s entire communications infrastructure. Reed is in the planning stages of a statewide collaboration to build and deploy a mobile communications system to use in such a disaster. “Conceptually the problem is this: open a map, point at a spot, and you have twenty-four hours to make that one of the most networked, connected places on the planet. How are you going to do it?” he asks.

After both 9/11 and Katrina, Reed says, several relief organizations arrived on the scene with communications devices, but none of the devices were compatible with each other. “They don’t interoperate,” Reed says. “So the police can’t talk to the firefighters, neither can talk to military, they can’t talk to civil defense. Although people were delighted that the Eighty-second Airborne went into New Orleans to restore order, the truth of the matter is that many of the radios that those folks used are Vietnam-era radios. And they don’t interoperate with anything that’s in use now.

“We’re looking at the whole technical process of being able to build mobile communications that a single individual could carry in and deploy,” Reed says. The system might be solar- and battery-powered and use wireless internet connections, satellite phones, and multispectrum radios. “You can imagine a single individual either driving in or walking up with a backpack, being able to set up around an area and create a robust communication capability where there was none before.” Technology such as cell phones and wireless internet connections has in the last five years become inexpensive enough and small enough to make Reed’s vision a reality. “You could have built that technology ten years ago,” he says, “but you would have needed a semitrailer truck to drive it around.”

Reed also plans to take advantage of the fastest processors around to do “integrated disaster response planning.” That means creating models that take into account weather, communications, transportation routes, and even human behavior to help plan evacuations, for example. “You analyze reversing lanes of highways, how much lead time is needed for evacuation, and what the timelines are for movements from different places,” he says.

“We’re trying to put better tools in the hands of those folks at the state level that plan for these things,” Reed says. “Disaster response is a science problem; it’s a public policy problem; it’s a communications and transportation problem. No one group has all of the skills and knowledge to solve the entire problem. So bringing people together from different disciplines and looking at integration technology is what the Renaissance Computing Institute is trying to do.” Luettich also hopes that more collaborations among geographers, marine scientists, and hydrologists will happen because of the spotlight that Katrina has put on hurricane preparedness.

Most of the Carolina researchers say that we’re more prepared for hurricanes and flooding than we were when Floyd hit. Eleven communities in North Carolina are developing hazard mitigation plans to serve as models for others in the state under a state grant program. The floodplain remapping will help too, Band says. New floodplain maps have been released for many of the areas around the Neuse and Tar Rivers, and maps for more areas should be released soon (for details, see www.ncfloodmaps.com).

But no matter what you draw on the map, at some point there will be a flood that we’re not prepared for, Moreau says. “In the case of Hurricane Floyd, it was estimated to be a five-hundred-year flood, based on data at the time. So if you’re trying to protect against a one-hundred-year flood, and you get a five-hundred-year-flood, it’s too bad,” he says.

“There’s just so much protection that you can put out there,” Moreau says. “Nature’s going to have its way. So get out of its path.”

Fraser’s report was funded by FEMA and the National Science Foundation. Brian Blanton is research assistant professor of physical oceanography.