What makes a person likely to acquire HIV? Serving time in prison is one risk factor among many. The Bureau of Justice reported in 2003 that the rate of confirmed AIDS cases was more than three times higher among the prison population than in the United States overall. But that’s not to say that prison time is the cause; it’s much more complicated than that.

What motivates a person to reduce his or her risk of acquiring HIV may, on the other hand, have a relatively simple answer — at least for a certain group of incarcerated women during their transition back into society. One UNC research team is basing its study on the idea that mothers want to stay healthy for their families. And when families are stable and bonds are strong, that motivation is even stronger.

Cathie Fogel works with incarcerated women, testing HIV risk-reduction and prevention interventions. She says that these women have a higher risk of acquiring HIV because of factors in their personal histories: substance abuse, depression, childhood violence or sexual abuse, current violent relationships, and exchanging sex for drugs.

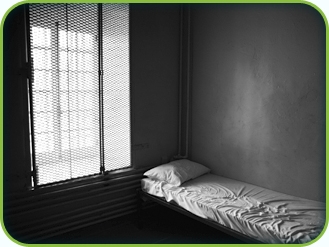

The National Institute of Mental Health has awarded Fogel a grant to explore what it’s like to be a mother leaving prison. As part of her study — “Incarcerated Women, Parenting, and HIV Risk” — Fogel plans to research the women’s reentry and reunification into society, and examine programs inside the prison system as well as the resources that are waiting for mothers after serving their terms. An incarcerated woman has an elevated risk of acquiring HIV upon returning to her community, Fogel says. “They have so many risk factors, much of what got them into prison to start with.”

Unstable and violent childhood experiences, which are common among incarcerated women, increase the likelihood of substance abuse later in life — and substance abuse is one risk factor for HIV. Fogel and co-investigator Anna Scheyett, a clinical associate professor in UNC’s School of Social Work, will explore ways to reduce HIV risk for women during the transition back to society after serving time.

They’ll also investigate ways to help the women strengthen their bonds with their children, and improve their relationships with other people. “You can’t be a mother if you weren’t mothered,” Scheyett says. As the project’s expert on community resources, Scheyett will explore programs that address the needs of an incarcerated woman’s family.

A community resource that helps parents provide food and housing also enables mothers to focus on protective behaviors, such as condom use. Returning to a community after serving time means returning to stressful responsibilities and relationships. With a lower stress level, a mother can prioritize her own sexual health, thus reducing her risk of acquiring HIV.

“So children themselves, and also learning to be better parents, motivate women to stay healthy,” Fogel says. Her ongoing study made it clear to her just how important the women’s children are to them, even though the families are separated. Fogel recognized that motherhood alone can motivate women to reduce their own HIV risk. “You can’t be a good parent if you’re not healthy, right?” she says. “So that’s how the two pieces come together.”

Catherine Fogel is a women’s health care nurse practitioner and professor in the School of Nursing.