Walking along the elevated shoreline of Jordan Lake, something catches Ayla Gizlice’s eye. She slides down the eroded bank, crouching with her weight on her heels, and navigates over a massive tangle of tree roots. Delicately picking up a large piece of clay, she inspects its texture and color. After putting a few hunks of the sediment into a bag, she stands and scans the shoreline ahead. The search continues.

Last year, Gizlice studied the history and environmental issues of Jordan Lake during a capstone course. Since then, she has returned to the reservoir countless times to find objects to incorporate into her senior thesis art project.

“I feel like, with environmental issues, there’s a tendency to either deny or disassociate,” she says. “I want people to look at the problems head on and consider how they might play a role in the environment and how the environment might affect them.”

Gizlice untangles a plastic bag from a tree branch along the shore of Jordan Lake. With a plant pathologist as a mom, a dad with a PhD in plant genetics, and multiple extended family members who are artists, Gizlice’s choice to double-major in both environmental science and studio art was almost a given. “I came into the environmental science major most excited about advocacy,” she says. “I think that’s something I can definitely pursue through the lens of art.”

Gizlice untangles a plastic bag from a tree branch along the shore of Jordan Lake. With a plant pathologist as a mom, a dad with a PhD in plant genetics, and multiple extended family members who are artists, Gizlice’s choice to double-major in both environmental science and studio art was almost a given. “I came into the environmental science major most excited about advocacy,” she says. “I think that’s something I can definitely pursue through the lens of art.”

Over the past six months, Gizlice has spent hours at the lake and surrounding streams collecting materials like clay, fish bones and carcasses, plastic bags, and large rocks.

Over the past six months, Gizlice has spent hours at the lake and surrounding streams collecting materials like clay, fish bones and carcasses, plastic bags, and large rocks.

Development of Jordan Lake began in 1963. Called the New Hope Project, the man-made lake was created in the wake of several flooding disasters. The goal was to build a dam and create a reservoir that would prevent future flooding — a controversial decision that required the movement of entire communities. These days, scuba divers can still explore structural remains of the towns that once existed there, including the foundations of former homes and barns.

Development of Jordan Lake began in 1963. Called the New Hope Project, the man-made lake was created in the wake of several flooding disasters. The goal was to build a dam and create a reservoir that would prevent future flooding — a controversial decision that required the movement of entire communities. These days, scuba divers can still explore structural remains of the towns that once existed there, including the foundations of former homes and barns.

Gizlice uses a ribbon tool to create a clay vessel to hold her accumulated fish bones and carcasses. In total, she made 27 vessels for the project. “I realized how uniquely pliable the clay around the lake is, and I kind of wanted to put those two things together — the fish bodies and the clay,” she says.

Gizlice uses a ribbon tool to create a clay vessel to hold her accumulated fish bones and carcasses. In total, she made 27 vessels for the project. “I realized how uniquely pliable the clay around the lake is, and I kind of wanted to put those two things together — the fish bodies and the clay,” she says.

A fish spine sits on Gizlice’s work table in her studio. Although litter is a big issue at Jordan Lake, Gizlice thinks the more troubling concern is water pollution. For decades, excessive discharge of nitrates into the water has caused algal blooms that lead to low oxygen levels and poor water quality, according to the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality.

A fish spine sits on Gizlice’s work table in her studio. Although litter is a big issue at Jordan Lake, Gizlice thinks the more troubling concern is water pollution. For decades, excessive discharge of nitrates into the water has caused algal blooms that lead to low oxygen levels and poor water quality, according to the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality.

Gizlice hopes that including actual bones and carcasses will send a stronger message than abstract depictions of dead fish. “I think there is a degree of separation that happens when you have a representation of an object or an issue,” she says. “By having the actual bodies that resulted from these environmental issues there’s a more immediate reaction.”

Gizlice hopes that including actual bones and carcasses will send a stronger message than abstract depictions of dead fish. “I think there is a degree of separation that happens when you have a representation of an object or an issue,” she says. “By having the actual bodies that resulted from these environmental issues there’s a more immediate reaction.”

Sticking to the organic nature of her project, Gizlice shaped the clay vessels according to the natural shape of the fish bones and carcasses, but sometimes branched out from this idea. “If the fish body wasn’t really apparent, I tried to take it in the direction of letter forms so that when it’s all laid out in a line its sort of like a hieroglyphic or cryptic text,” she says.

Sticking to the organic nature of her project, Gizlice shaped the clay vessels according to the natural shape of the fish bones and carcasses, but sometimes branched out from this idea. “If the fish body wasn’t really apparent, I tried to take it in the direction of letter forms so that when it’s all laid out in a line its sort of like a hieroglyphic or cryptic text,” she says.

Gizlice prepares to weld a flag stand for the plastic she found at the lake and surrounding streams. She calls her approach a “performative ecological proposition.”

Gizlice prepares to weld a flag stand for the plastic she found at the lake and surrounding streams. She calls her approach a “performative ecological proposition.”

“It’s really wordy,” she says while laughing. “But it means forcing me to work a lot harder for the materials. Rather than creating something from materials that don’t really hold meaning on their own, these objects had meaning and existed perfectly outside of my project.”

Gizlice welds a metal rod around a rock as the base of a flag pole.

Gizlice welds a metal rod around a rock as the base of a flag pole.

For the project, Gizlice specifically honed in on white plastic bags. Gathering them not only served as a functional component, she says, but the act of collecting the litter was also a way for her to undo negative human impact on the local environment. “It’s a white flag which seems a little bit like a surrender,” she says. “It’s the environment surrendering to human intervention.”

For the project, Gizlice specifically honed in on white plastic bags. Gathering them not only served as a functional component, she says, but the act of collecting the litter was also a way for her to undo negative human impact on the local environment. “It’s a white flag which seems a little bit like a surrender,” she says. “It’s the environment surrendering to human intervention.”

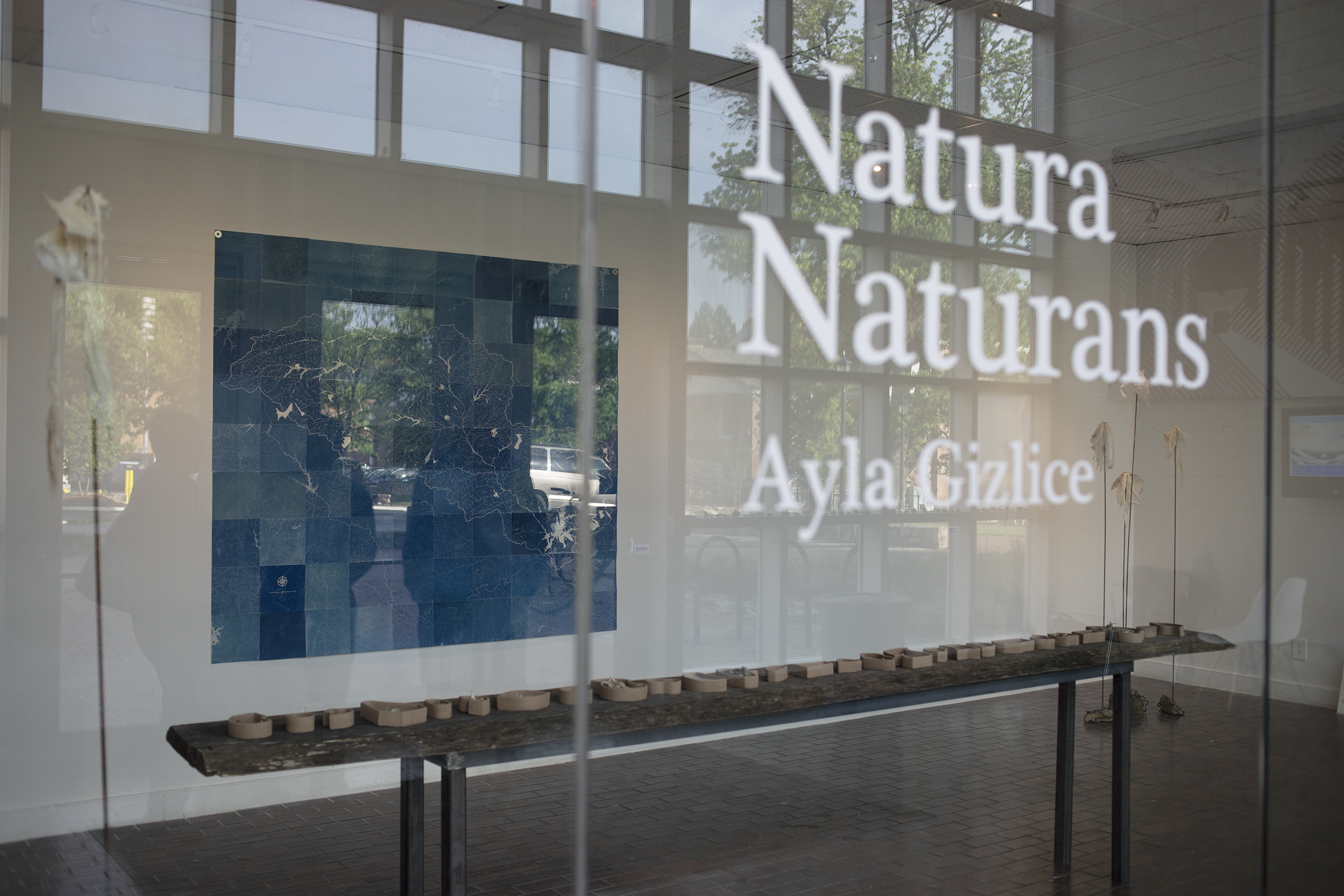

Gizlice named her piece “Natura Naturans” — a Latin term that roughly translates as “to nature,” implying that the environment is always in flux. “I wanted to focus on the prospect of change,” she says. “I think that’s much more hopeful.”

Gizlice named her piece “Natura Naturans” — a Latin term that roughly translates as “to nature,” implying that the environment is always in flux. “I wanted to focus on the prospect of change,” she says. “I think that’s much more hopeful.”

A large part of Gizlice’s research looked at the Army Corps of Engineers’ environmental impact statements and letters from concerned citizens prior to the lake’s development. “It seemed like a really good primary source to draw inspiration from, but it was also just interesting to me because of how different their predictions about the lake were from reality,” she says. One of those predictions stated that the reservoir’s water level would only vary by about three feet — but after the 2018 hurricane season, the water level was about 16 feet higher than normal.

A large part of Gizlice’s research looked at the Army Corps of Engineers’ environmental impact statements and letters from concerned citizens prior to the lake’s development. “It seemed like a really good primary source to draw inspiration from, but it was also just interesting to me because of how different their predictions about the lake were from reality,” she says. One of those predictions stated that the reservoir’s water level would only vary by about three feet — but after the 2018 hurricane season, the water level was about 16 feet higher than normal.

Gizlice chats with guests during a reception for her project. Having just graduated with her bachelor’s degree, she strives to continue her education and advocacy — potentially through a combined art and ecology grad program.

Gizlice chats with guests during a reception for her project. Having just graduated with her bachelor’s degree, she strives to continue her education and advocacy — potentially through a combined art and ecology grad program.