“Loud noise!” Kenly Cox warns as she fires up a table saw. Unfazed, her colleague, Kira Lyon marks a slab of wood, careful to be exact.

“We’ve got 45 minutes,” notes Lyon and both speed up their tasks.

The two are properties artisans for PlayMakers Repertory Company, building prototypes of military-style trunks for the upcoming show, “Native Son.” Although the show is still weeks away, they must complete two trunks for the day’s production meeting.

Now, you might be thinking, a trunk is a trunk, right? Wrong. Everything on stage — costumes, set design, even the cast iron pan a character uses to kill a rat — is carefully thought out.

“You’re trying to accurately represent a time and a place in history that can also add to the understanding of the show, understanding of what these characters are going through,” says Andrea Bullock, PlayMakers’ properties master.

“Native Son,” which premiered at PlayMakers in September, tells the story of Bigger Thomas, a young black man living in Chicago in the 1930s. After he accidentally kills a wealthy white woman, hides the evidence, and flees, the audience journeys deeper into Bigger’s life, seeing the systemic racism and poverty that led to that point.

Properties artisans Kira Lyon and Kenly Cox build prototypes of military-style trunks for the upcoming show. The team tries to be as accurate as possible with every prop on set. And if the props and the time period or setting don’t match? “Someone in the audience is gonna know. They always will,” Bullock laughs. “And they’ll call you out on it, too.”

Properties artisans Kira Lyon and Kenly Cox build prototypes of military-style trunks for the upcoming show. The team tries to be as accurate as possible with every prop on set. And if the props and the time period or setting don’t match? “Someone in the audience is gonna know. They always will,” Bullock laughs. “And they’ll call you out on it, too.”

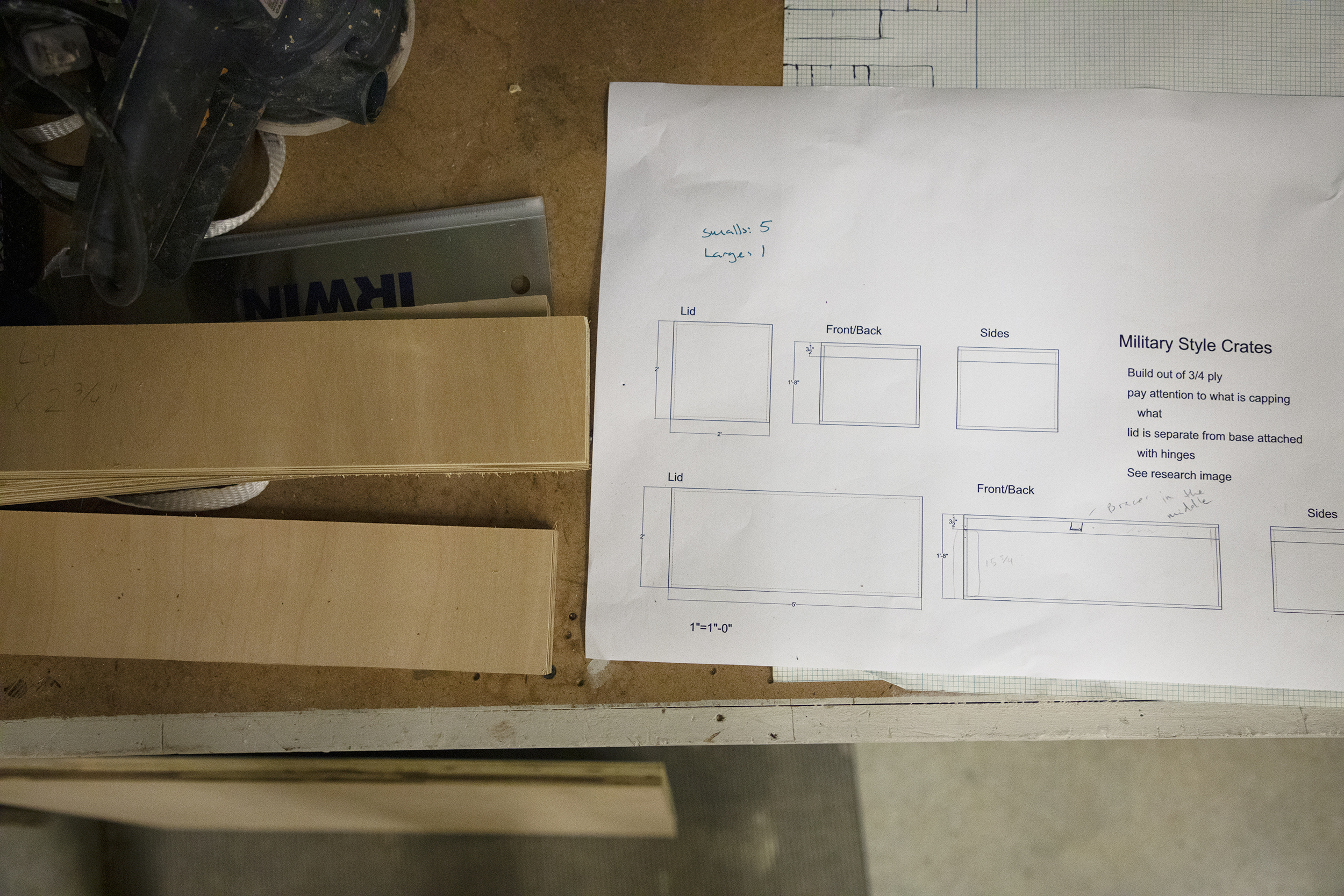

A design for trunks sits on a work table in the prop workshop. Creating props has changed dramatically since Bullock started 13 years ago, largely due to the internet. “The amount of information that’s online — it’s insane and wonderful and opened up so much more research.” Bullock uses a plethora of resources like museum and university websites, newspaper archives, décor books, photographs, and paintings for inspiration. “I love history,” she says. “I’m always interested in our technological evolution, like washing machines or sewing machines, seeing those changes and digging into them.”

A design for trunks sits on a work table in the prop workshop. Creating props has changed dramatically since Bullock started 13 years ago, largely due to the internet. “The amount of information that’s online — it’s insane and wonderful and opened up so much more research.” Bullock uses a plethora of resources like museum and university websites, newspaper archives, décor books, photographs, and paintings for inspiration. “I love history,” she says. “I’m always interested in our technological evolution, like washing machines or sewing machines, seeing those changes and digging into them.”

The team will make a variety of props for the show including 14 crates, newspapers, a hatchet, and a furnace with billowing smoke.

The team will make a variety of props for the show including 14 crates, newspapers, a hatchet, and a furnace with billowing smoke.

Costumes are fitted to mannequins in the costume shop. Jennifer Bayang, assistant costume director, estimates “Native Son” requires 17 to 20 looks spread out among nine actors.

Costumes are fitted to mannequins in the costume shop. Jennifer Bayang, assistant costume director, estimates “Native Son” requires 17 to 20 looks spread out among nine actors.

UNC grad student Alex Hagman marks a pattern prior to cutting fabric for a costume. For “Native Son,” the shop will put together about 100 pieces, by reusing clothing from the shops’ archive, altering purchased items, or creating new ones from scratch.

UNC grad student Alex Hagman marks a pattern prior to cutting fabric for a costume. For “Native Son,” the shop will put together about 100 pieces, by reusing clothing from the shops’ archive, altering purchased items, or creating new ones from scratch.

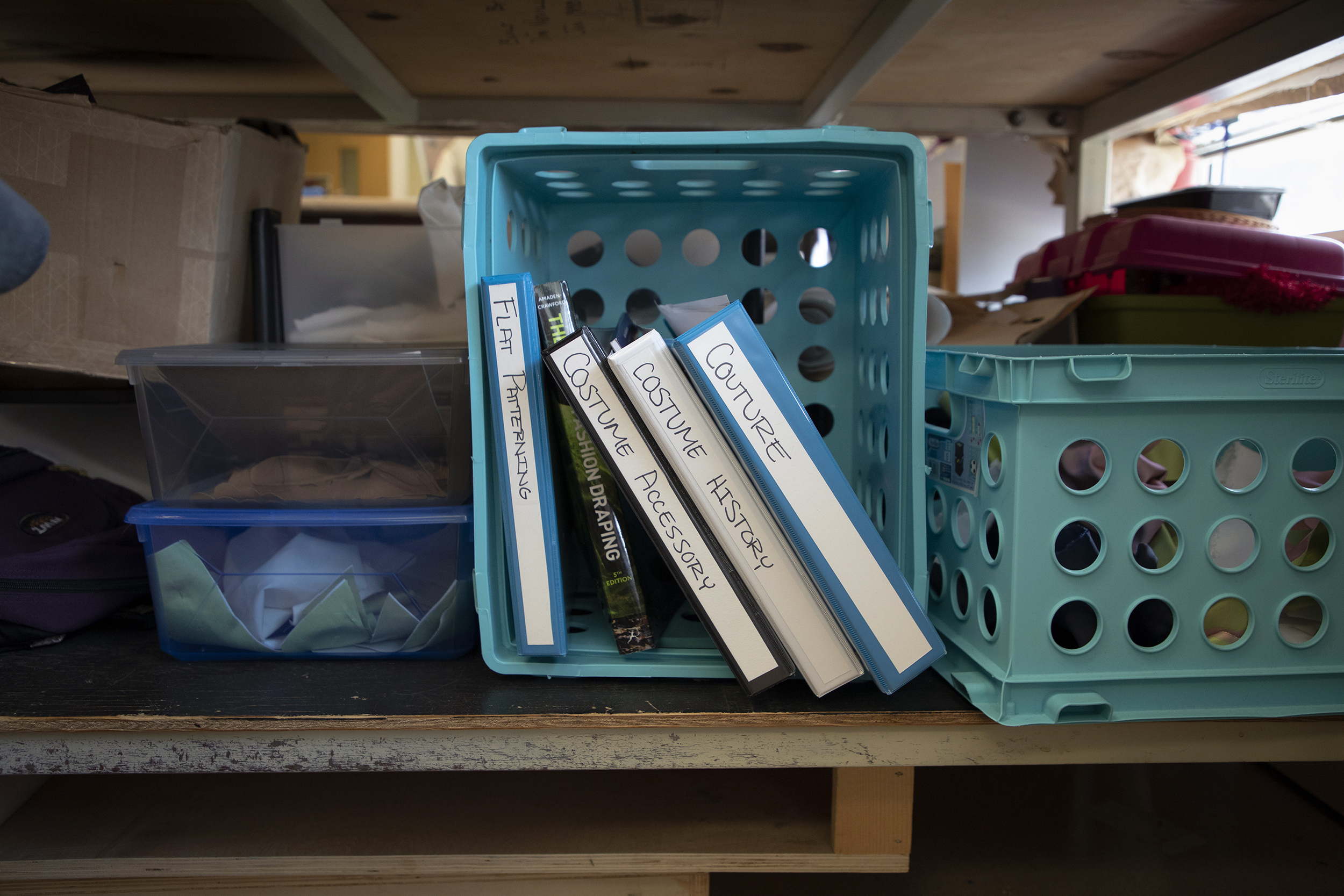

Study materials, including those on costume accessory, costume history, and couture, sit underneath a work table in the costume shop. Clothing for the show not only has to be accurate for the 1930s — like overcoats, floral day dresses, and oxfords — but accessible for the stage. For example, one scene calls for a character to do the splits, something she can’t do wearing a long, straight-cut skirt. The costume team modified the outfit, creating a wrap skirt with deep pleats to allow movement. “It’s always a balance between what’s historically accurate and what’s functional,” says Triffin Morris, head of the costume shop.

Study materials, including those on costume accessory, costume history, and couture, sit underneath a work table in the costume shop. Clothing for the show not only has to be accurate for the 1930s — like overcoats, floral day dresses, and oxfords — but accessible for the stage. For example, one scene calls for a character to do the splits, something she can’t do wearing a long, straight-cut skirt. The costume team modified the outfit, creating a wrap skirt with deep pleats to allow movement. “It’s always a balance between what’s historically accurate and what’s functional,” says Triffin Morris, head of the costume shop.

UNC graduate student Kevin Pendergast cuts metal for a 32-foot retractable wall with window panes, meant to resemble airplane hangar doors. “That came from the idea that Bigger, the main character, wanted to be an airplane pilot but couldn’t,” says Jessica Secrest, PlayMakers’ scenic charge artist. “Everything [in the play] was taking place in his world, and his world was this dream that never manifested.”

UNC graduate student Kevin Pendergast cuts metal for a 32-foot retractable wall with window panes, meant to resemble airplane hangar doors. “That came from the idea that Bigger, the main character, wanted to be an airplane pilot but couldn’t,” says Jessica Secrest, PlayMakers’ scenic charge artist. “Everything [in the play] was taking place in his world, and his world was this dream that never manifested.”

Students wrap aluminum sheets around wood to create the illusion of large, metal pillars. Before building starts, the set designer sends Secrest research images and examples of paint treatments to incorporate into the set’s construction. As a scenic artist, it’s Secrest’s job to translate those ideas into reality.

Students wrap aluminum sheets around wood to create the illusion of large, metal pillars. Before building starts, the set designer sends Secrest research images and examples of paint treatments to incorporate into the set’s construction. As a scenic artist, it’s Secrest’s job to translate those ideas into reality.

UNC grad students Patrick Hardison and Rocky Love work in the set design shop. The set team for “Native Son” is made up of about 15 people including staff, work study students, graduate students, and undergraduate assistants.

UNC grad students Patrick Hardison and Rocky Love work in the set design shop. The set team for “Native Son” is made up of about 15 people including staff, work study students, graduate students, and undergraduate assistants.

An actress dances on a crate during a performance. “Lightweight and portable is what everybody likes,” Bullock says in regard to props. “But they also like to jump and stand and dance on it.”

An actress dances on a crate during a performance. “Lightweight and portable is what everybody likes,” Bullock says in regard to props. “But they also like to jump and stand and dance on it.”

“Before anybody in the play ever opens their mouth, how the clothes look can give you a sense of the journey you’re about to go on,” Morris says. Just by looking at a character’s outfit, the audience should be able to gather information like social status and where the story takes place.

“Before anybody in the play ever opens their mouth, how the clothes look can give you a sense of the journey you’re about to go on,” Morris says. Just by looking at a character’s outfit, the audience should be able to gather information like social status and where the story takes place.

Secrest estimates that it took up to two weeks to paint the stage, which mirrors Bigger’s shattered aspirations. “It was a patriotic symbol of America but over the years it became tattered. It’s not taken care of so it disintegrates,” Secrest explains. “Much like the dreams of Bigger, the American dream is slowly disintegrating.” Secrest says every aspect of production is a thoughtful decision. “The actors create their characters; the designers create their world.”

Secrest estimates that it took up to two weeks to paint the stage, which mirrors Bigger’s shattered aspirations. “It was a patriotic symbol of America but over the years it became tattered. It’s not taken care of so it disintegrates,” Secrest explains. “Much like the dreams of Bigger, the American dream is slowly disintegrating.” Secrest says every aspect of production is a thoughtful decision. “The actors create their characters; the designers create their world.”