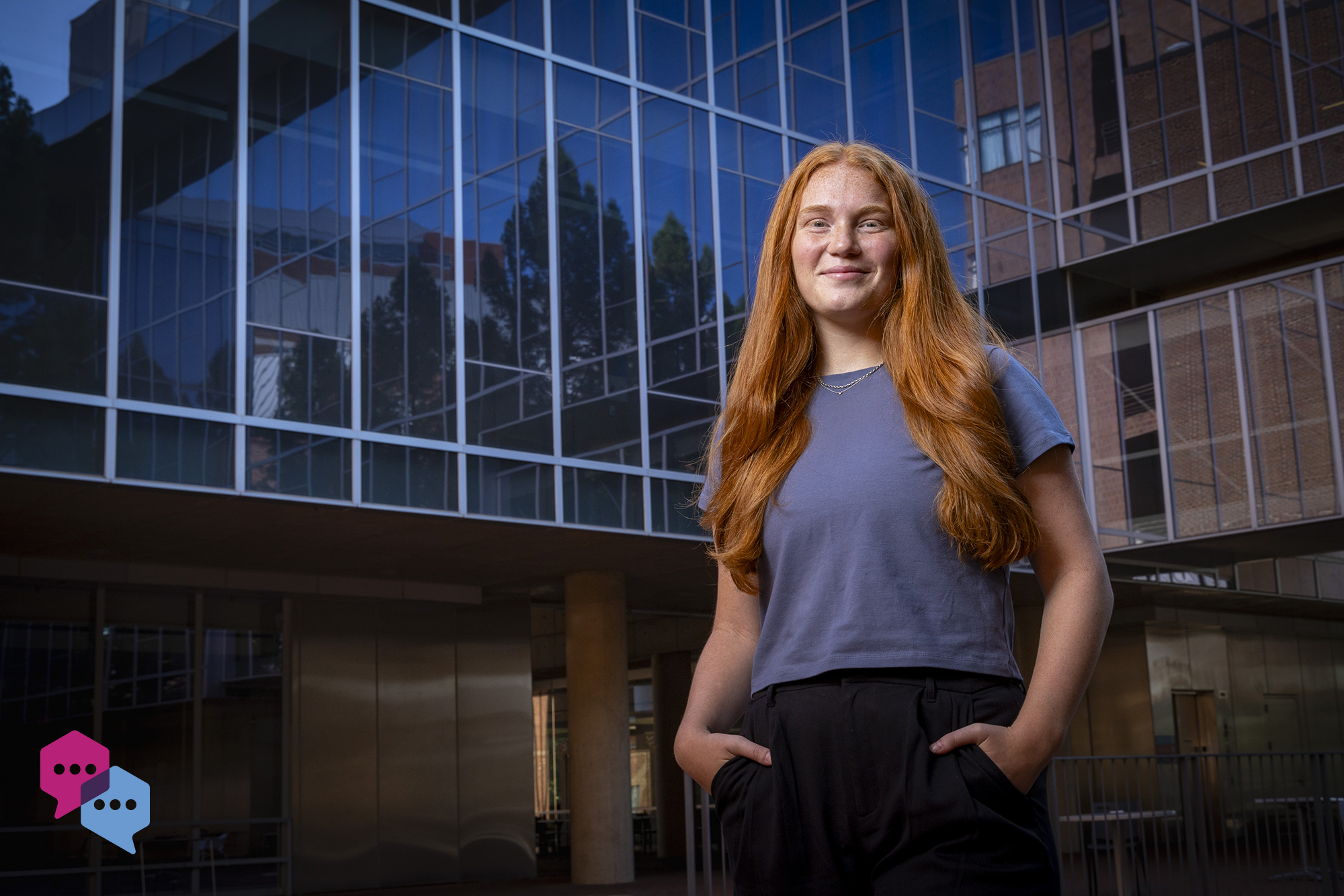

Lilly Papell is a senior majoring in biology and minoring in chemistry and creative writing within the UNC College of Arts and Sciences. She studies how genome organization within microscopic animals called tardigrades plays a role in how they survive the DNA-damaging environments — such as ionizing radiation and desiccation — that would kill most lifeforms.

Q: How did you discover your specific field of study?

A: In my junior year of high school, my AP Biology teacher told us that babies start off with what are essentially “paddles of skin” as hands. During development, a process called apoptosis kills the skin cells between what will become fingers. Ever since that lesson, I’ve been fascinated with development and the molecular mechanisms that make each organism unique. I ended up becoming a lab assistant for that teacher, furthering my passion for biology until I decided to major in it at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Attending a research university was a great opportunity to apply my interests to hands-on projects. I was introduced to tardigrades by the Goldstein Lab my sophomore year to study the development of a microscopic organism that can survive some unbelievably extreme environments.

Q: Academics are problem-solvers. Describe a research challenge you’ve faced and how you overcame it.

A: Tardigrades are small — usually less than a millimeter long — and I work with their embryos, which are even tinier. One of the steps I had to learn to perform my experiments was how to cut the embryos out of their eggshells. To me, it felt like trying to hit the bullseye of a target. It was frustrating staring into a microscope for hours and trying to maneuver the needle to nick an eggshell without cutting the embryo in half.

The first few attempts, I probably had a 10% success rate. I knew it needed to improve or else I wouldn’t accomplish any of my experimental goals. It was a small step in the protocol that made a huge difference. My graduate student mentor and I decided to schedule eggshell cutting sessions where we would sit and practice. I eventually got the hang of the repetition and required patience. It’s still not my favorite thing to do, but it’s true what they say: Practice makes progress.

Q: Describe your research in five words.

A: Tiny tardigrades have mighty mechanisms.

Q: Who or what inspires you? Why?

A: I had never experienced the environment of a research lab before joining the Goldstein Lab. It didn’t take long for me to realize how passionate my other lab members were to share their projects and collaborate. I can’t count the number of times I’ve been overwhelmed by the flood of advice and proposed future experiments that were given purely out of the love for science. They motivate me to keep learning so I can contribute to the conversation and return the favor.

Q: If you could pursue any other career, what would it be and why?

A: An author. I’ve always been a bookworm. One of the main reasons I came to Carolina was to minor in creative writing alongside my biology major. I’ve always loved the idea of imagining a world like “The Hunger Games” or “Divergent” that people could relate to and be inspired by. I still write poems and short stories in my free time, but my dream would be to publish books and have a scientific career.