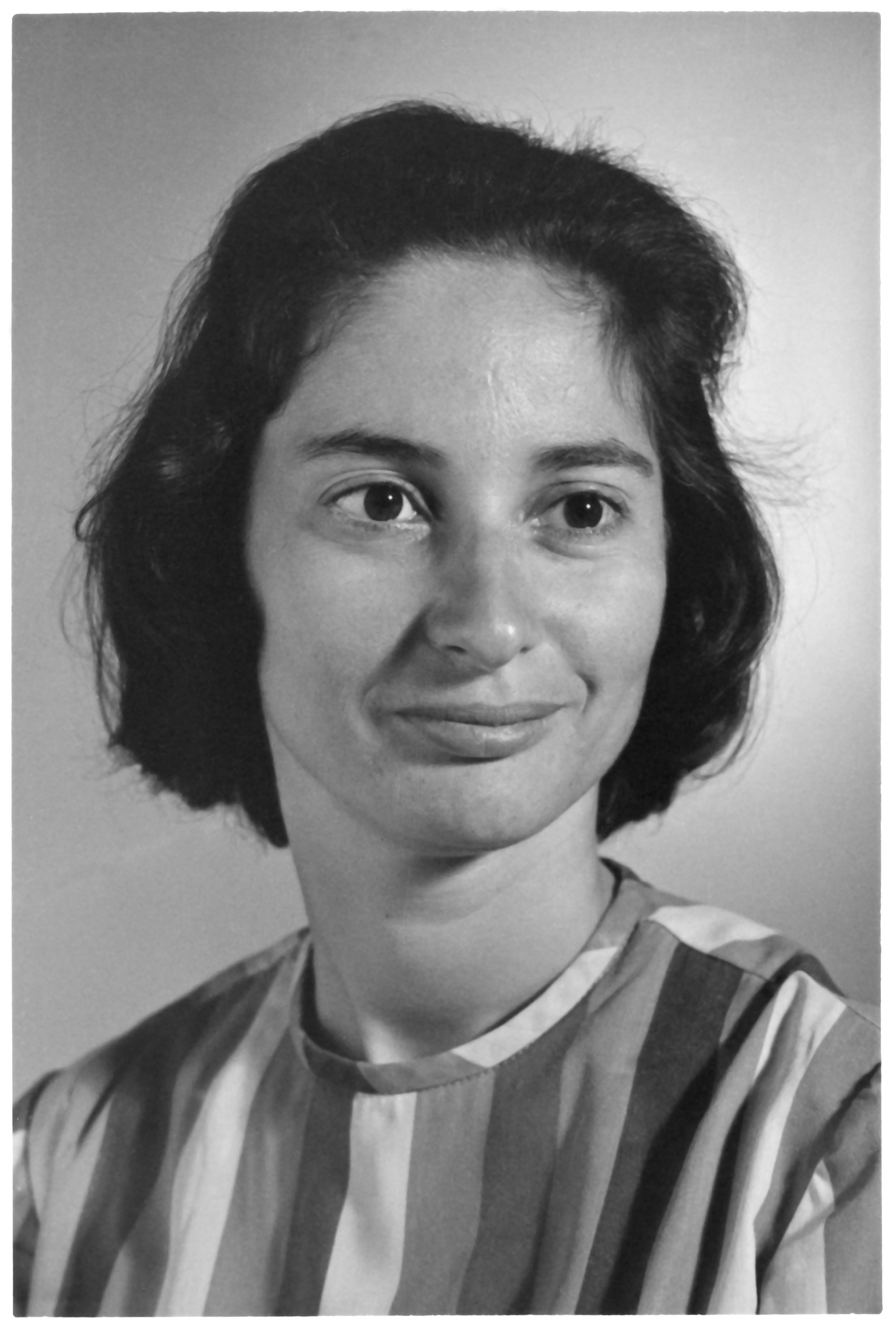

Deborah Dexter, a 23-year-old PhD candidate from the UNC Institute of Marine Sciences, stands on the deck of a large research vessel 100 miles off the coast of Peru. She is holding netting connected to a cable that will be dropped into the depths of the Atacama trench — about 6,000 feet deep. It takes several hours to collect just one sample so she and the other scientists work in shifts around the clock. Of the 30 researchers on board, Dexter is the only woman. The year is 1964.

During the month-long expedition, Dexter works hard. She never complains and she never gets sea sick. But she does occasionally get singled out for being a woman. “When the guys wanted to watch movies, they told me to get a book and go read somewhere else,” Dexter recalls. “I don’t know what kinds of movies they were, but I guess they wanted to make a lot of remarks that I might not like.

“I knew I was being deliberately pushed out of that, but I couldn’t care that much,” Dexter says. “At the time, I just thought I was so lucky to be on the ship and to be doing those things.” She considered going to another room to read a book (something she enjoyed doing anyway) a small price to pay for the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

“It was a really unbelievable thing — to have one female scientist on board. It just didn’t happen that way back then.”

Unique family values

The household that Dexter grew up in placed enormous value on education. Dexter and all three of her brothers went to college. Her father went to Stanford for his undergraduate work and then earned an MBA from Harvard Business School. Her mother earned an undergraduate degree in 1931 — just 11 years after women gained the right to vote.

“If I had told my parents, when I was 17, that I wanted to get married and have kids they would have had a fit. But I never even thought of that as a possibility,” she says. “There was no question, when I was that age, that I would go to the university. That’s just what you did — we were very lucky.”

Dexter’s curiosity about marine life started when she was a child. “My grandmother lived in Hermosa Beach and I got to go down there as a kid. We would walk down the beach every morning and dig in the sand.” In high school, Dexter excelled in all of her science classes, but her favorite was biology — which she decided to pursue as her major when she got to Stanford.

Her parents encouraged her to become a doctor, “and I thought that would be alright,” she says. But the summer after her sophomore year at Stanford, Dexter spent six weeks at the Hopkins Marine Station, located 90 miles south of the university on the Monterey Peninsula. At the marine station, class schedules were determined by the tides — when the tide was low, Dexter and the other students were out on the beaches collecting organisms. “Whatever the topic was, we saw it live out of the ocean, and then we’d look at it under the microscope,” she says. “I took two courses in marine invertebrates, and that was the end of me wanting to go to med school.”

Straight to a PhD

Dexter stayed at Stanford after finishing her undergraduate courses to complete a master’s in education before applying to PhD programs. When Dexter was accepted to UNC, she was the only woman in her class approved to go straight into the PhD track — because she already had a master’s degree. “All the women had undergraduate degrees but no master’s degrees — so they were required to get the master’s degree before they could go on for a PhD because it was assumed they were going to get married and drop out,” Dexter says. “The guys could go straight into a PhD program from undergrad, but not the women.”

Dexter spent two years doing coursework on UNC’s main campus before moving to Morehead City. She lived in a small house nextdoor to the Institute of Marine Sciences (IMS) and paid $60 a month for rent. Her days were mostly spent on Radio Island — digging cores into the sand and collecting organisms. “People would come up to me on the beach and ask what in the world I was doing,” Dexter says, chuckling. She stored her samples — most of which were amphipods — in glass jars that she would then take back to the lab.

Back then, IMS was called the Institute of Fisheries Research, and Dexter was the only student in residence there. Other students would come down from UNC’s main campus to stay for a few days or a month, but Dexter was the first to live in Morehead City for the duration of her PhD work. “I guess, in one sense, you could say I was a loner. But I didn’t feel like a loner,” she says. “I was interacting with people constantly. The faculty pulled me into everything.”

The warm, communal culture that exists at IMS today was alive and well back in the ’60s — even with fewer people around. “We would all bring our brown bag lunches and eat together and talk about our science,” she says. “Most of my work was on the beach, but I got to go out on the boats with people. It was fun — the beach is not a bad place to live.”

In addition to working at IMS, Dexter attended seminars at the Duke Marine Lab, and even took a few classes there. By networking with people at Duke, she was offered the opportunity to join the research expedition in Peru. And proving her salt on that trip, Dexter says, helped open up many more doors for her.

Dexter at her home in Los Altos, California. While she is retired from teaching, Dexter remains active in the local community. Photo by Mary Lide Parker

World travels

Peru. Panama. Costa Rica. Australia. Israel. Thailand. During the span of her career, Dexter’s research took her to hundreds of beaches in dozens of countries, across six different continents.

Dexter’s travels could fill a book, but one experience in particular stands out in her mind — when she received a Fulbright scholarship to teach deep sea biology to college students in Egypt.

“They had never had an American professor,” Dexter says. “I came in and wrote my name on the board in Arabic, but the class — like all science classes there — was taught in English.” The typical structure of a class, according to Dexter, consisted of a professor writing notes on the board, the students copying those notes down word for word, and then memorizing them. If a student needed help, he or she would pay the instructor to help them. “I told them I would be fired for doing that in the United States,” Dexter says. “So I told them we were doing it my way.” Dexter held office hours (and would not accept payment for helping students outside of class), but, more importantly, she engaged them in a way these students had never experienced before.

“They were getting degrees in oceanography and they had never heard of a hydrothermal vent,” she says. “The class exploded when I started talking about it.”

She had about 30 students, nine of whom were women. When she took the class to the beach, she made a point of telling the women that she was planning to wear sweatpants and a sweatshirt. “I was not able to go in my bathing suit — that was totally inappropriate,” Dexter says. “That would be like going to class nude or something.” All of the women wore full-length galabeyas, or long dresses, and they weren’t allowed to swim unless they remained fully clothed. “I told them they were going to get wet, and they did, and they loved it. It was like a holiday for them.”

At the end of the semester, several students approached Dexter. “They told me they would never study the way they used to study,” she recalls. “They thought it was so much more interesting. You learn so much more. You think about it. You remember it.”

Beach lessons

Dexter employed the same hands-on approach in her many years of teaching at San Diego State University. On the rocky shore just 10 miles from campus, Dexter introduced her students to all kinds of creatures at low tide — sponges, sea urchins, almost every type of phylum, and sea cucumbers of all different sizes and colors.

Dexter covered the different organisms in the class and lab so the students would already be familiar with their anatomy. But the material didn’t come alive until they were in the environment. “We would go down to the beach and see seaweed all over the rocks. So you have to slip your fingers into a crevasse or turn over a rock so that they begin to see where these organisms are. Learning about their biology in a lab setting doesn’t do any good if you haven’t got a clue where or how to find them 10 miles away.

“If you do the right things, it doesn’t take that much to get your students excited,” she says. “And if you get them exited, they’re much more likely to work harder.”

In addition to hands-on learning, Dexter always emphasized teamwork. “I wouldn’t tolerate cliques,” she says. “I told my students they would eventually have to work with people they don’t like in their professional life. So they should go ahead and get over it.”

An advocate for education and equality

During Dexter’s time at UNC, there was just one woman in the biology department who was a regular tenured professor. Otherwise the entire faculty was male. “That was typical. You could go to Duke or anywhere in the country and see the same thing,” Dexter says. “There were some schools where, in certain fields, you weren’t even allowed to participate if you were a woman. It’s a very different scene now.”

Very different indeed. Today, the UNC Biology Department employs over 20 women — including Victoria L. Bautch, the Beverly Long Chapin Distinguished Professor and chair of the department.

“Back then, you were competing against a lot of things including the pressure that you don’t belong in a science because, in those days, women weren’t supposed to go into science,” Dexter says. “They were supposed to get married and have babies.”

When Dexter arrived at San Diego State University, the biological sciences were separated into four departments: biology, botany, zoology, and microbiology. She was the only woman in zoology. When the four departments were merged into Biological Sciences about 15 years later, Dexter was one of six women of approximately 60 faculty members.

When asked about the value of women in STEM, Dexter says having women well-represented in the sciences is not enough. “We need women in every job — just like we need men in every job. But they shouldn’t be chosen because they’re women or men.”

Almost 60 percent of college students in the United States are women, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Even so, Dexter says it’s not as easy for women to get ahead. “You have to be tougher than you might want to be, regardless of what your field is — whether it’s marine biology, physics, or English.” In her experience, Dexter felt she had to prove herself time and time again. But as time went on, it got easier. “You have to go with the flow,” she says. “If you can do that, you will get more and more opportunities because people will start to say, ‘This is a woman who can do this.’”