Every eastern North Carolinian can recount the day in September 1999 when Hurricane Floyd ripped through the state, dropping torrential rain onto unsuspecting victims. Floyd claimed 35 lives and caused $3.5 billion in damage to homes.

Rocky Mount suffered the worst flooding in the state, as rivers rose to nearly 24 feet — exceeding 500-year flood levels. According to the National Weather Service, the floodwaters covered more than 40 percent of the city for several days.

“The long-term psychological part of the flood is still present here, and I don’t know if we’ll ever recover from the magnitude of Floyd,” Fire Chief Keith Harris told WRAL on the 10-year anniversary of the storm. Harris led many of the search and rescue missions in his home town.

“Some of the firemen would dive down into the houses to see if people were in them,” Jeff Hoagland, a consultant for the city, says. “We got to the point where we were using prescription bottles to see if we had the right address and people.”

Looking at Rocky Mount today, it is hard to picture that murky brown water once consumed the entire community. The city doesn’t look like a victim of flooding because almost all of the damaged structures have since been torn down.

At the time Floyd hit, over 4,000 North Carolinians did not have flood insurance. Within one day, a presidential state of emergency made Rocky Mount eligible for assistance from FEMA.

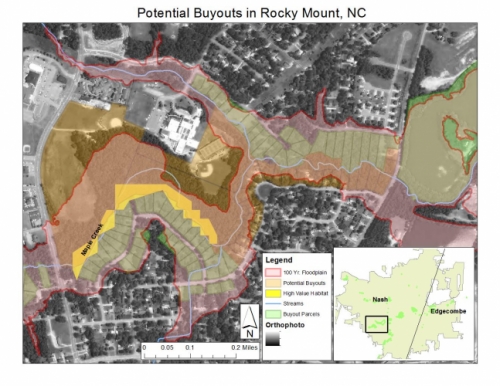

“We looked at a map on the wall in the city manager’s office and realized that the rivers had cut the city into three distinct pieces, almost like a pie,” Hoagland says. This flood pattern provided a natural solution for Rocky Mount — submit an application to the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP).

The HMGP, based within FEMA, offers funding to state and local governments after natural disasters so they can buy residents out of damaged or unrepairable homes — most often homes in low-lying areas prone to flooding. The program is completely voluntary, but aims to relocate as many people as possible.

With Rocky Mount properties divided by the flood, local government was able to quickly assess damages and select the most flood prone areas. This circumvented a common hurdle of buyouts — slow turnaround in appraisal and offers to homeowners.

“There is an urgency to get people out of harm’s way,” David Salvesen, a deputy director at UNC-Chapel Hill’s Center for Sustainable Community Design, says. “You have to buy out their homes before they can say, ‘We are just going to move back in!’”

Salvesen researches the effect of buyouts on aggregate risk, or the ability for purchasing properties in floodplains to prevent future flooding of the community. He has visited sites across the nation — five in North Carolina, four in Minnesota, and three in New Jersey.

Each of these sites serves as a case study for the project, which analyzes the overall success of the buyout process. Salvesen believes this evaluation can provide best practices for how to do buyouts the right way.

Because the HMPG is set up on an application basis, the money for buyouts must first be triggered by a disaster. “This makes it difficult to plan a buyout before the money to fund it is even provided,” Salvesen says.

In the face of a looming natural disaster, appropriate planning and preparation are important in every realm. Salvesen hopes his research can help towns select which homes could be purchased during the pre-planning stage.

While Salvesen studies the process of removing people from floodplains, he is also interested in the creative land use that stems from the buyout process. Acquired properties have been used for everything from disc golf courses to wildlife corridors to bike paths.

“The only rule is that you can’t put up walls,” Hoagland, who was a part of the Rocky Mount buyout, says. Rocky Mount turned much of its property into community parks where locals could barbeque or walk along the Tar River.

Salvesen saw potential in the blank slate created by these properties and partnered with Rebecca Kihslinger of the Environmental Law Institute to see how buyouts could benefit wildlife. Previously, the two researched how policy affects preservation of biodiversity and wetlands.

What they have found is that the more contiguous the properties, the better they serve wildlife. Buyouts must be structured to prevent what is referred to as the “gap tooth effect,” or acquisition of random pieces of properties.

Buyouts with connected properties, like those in Rocky Mount, are almost always marked as the most successful. In fact, out of all of the sites he has visited, Salvesen uses Rocky Mount as his prime example.

Through HMPG funding, and North Carolina doubling their money, Rocky Mount ended up with $117 million at their disposal. With this money, they were able to purchase 465 structures — nearly one-third of the homes damaged in the flooding.

“They did an amazing job removing so many homes from the floodplain,” Salvesen says. The impact of this work on risk reduction would soon be tested.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina spread torrential rain across the East Coast, including Rocky Mount. As the Tar River rose once again, only six years after Hurricane Floyd, it did so without taking any homes with it.

“Thank goodness the buyout program prevented people from going back and building in those areas or it would have happened again,” Hoagland says.

Hoagland believes the buyout was a game changer, and many locals share his opinion. Only 15 years after the buyout, almost everyone has forgotten that entire neighborhoods were on the buyout properties.

“As time goes by, there is very little mention that the property used to have a house or structure on it,” Hoagland says. “When the river rises, it just rises.”