The debate between President Donald Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden on Sept. 29 was heated from the get go, but just under 18 minutes in things really got messy. Chris Wallace, the moderator for the night, asked Biden if he would react to Amy Coney Barrett’s Supreme Court nomination by ending the filibuster or packing the court. Biden avoided the question, instead saying the American people should vote and let their senators know how they feel.

“He doesn’t want to answer the question,” Trump says.

“I’m not going to answer the question,” Biden responds.

“Why wouldn’t you answer the question? You want to put a lot of new Supreme Court Justices. Radical left.”

“Would you just shut up, man?”

“Listen, who is on your list, Joe?”

What ensued was almost a minute of the candidates talking over each other while Wallace attempted to get control of the situation that was quickly devolving.

While highly unusual for presidential debates to reach this level of combativeness, two people on opposite political sides unable to talk — and listen — to one another is more common as polarization continues to increase. Whether it be opinions about political issues like immigration or healthcare, presidential or congressional approval ratings, or even COVID-19 precautions, it’s becoming rarer for people to see eye-to-eye. In fact, we can’t even agree on what the most pressing problems are in the first place.

To disagree is one thing, but increasingly, voters look at those across the political aisle with disdain. In a 2019 survey by the Pew Research Center, participants were asked to associate a list of positive and negative words — like closed-minded, open-minded, lazy, or hardworking — with their political counterparts. Among Democrats surveyed, the top responses were Republicans are more closed-minded, unpatriotic, and immoral than other Americans. Republicans saw Democrats as more closed-minded, immoral, and unintelligent than other Americans.

Perhaps nowhere is this sentiment more obvious than on social media news feeds.

A common scapegoat

An onslaught of bad press ties social media platforms to election meddling, extremist groups, disinformation, and atrophied social skills among young people, so it’s easy to blame the platforms for increased polarization as well.

It doesn’t take much scrolling on Facebook or Twitter to confirm suspicions: Many people find their social media feeds teeming with combative political discussions.

A survey in July by the Pew Research Center shows that about 55 percent of adult social media users say they feel “worn out” by political posts and discussions on the platform. Additionally, 72 percent say discussing politics on social media with people they disagree with leads them to believe they have less in common with the other, politically, than initially thought. That’s up from 64 percent in 2016.

But Deen Freelon and Shannon McGregor — both professors in the UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media and researchers at the UNC Center for Information, Technology, and Public Life — caution that this link between social media and polarization isn’t so straightforward.

CHAPEL HILL- While Remy Reya enjoys in-person political discussions, he avoids engaging in those topics online.

“It’s very hard to have really constructive dialogue on social media just because of the nature of the platform,” he says. “It tends to bring out the kind of emotional, reactive conversation. I think people are kind of operating in different spheres of reality based on the information or misinformation they’re consuming, so I think that’s a real problem.”

“This social dissonance existed anyway,” says McGregor, who studies the role of social media and data in political processes. “Are they exacerbated? Absolutely. But, although these platforms need to do a lot more to do better, we can’t blame all our ills on them.”

One argument for increased polarization due to social media is that algorithms create “information silos” in which people’s newsfeeds tend to be full of information they agree with from like-minded individuals. While this isn’t helpful in creating well-rounded opinions, McGregor says, it reflects our social reality — people gravitate toward others they socially and politically align with.

Freelon, who researches online political communication, agrees that social media might be one factor among many that has increased voter polarization.

“You have to be very careful when you’re trying to demonstrate that sort of effect because, typically, media does not work in a linear way to cause people’s behaviors,” he says. “It works in tandem with many other influences, so its specific contribution is very difficult to sort out.”

So, if the rise in social media platforms over the course of the last decade isn’t the creator of the growing polarization among voters across that same time period, what is?

Worlds apart

In the book Prius or Pickup? UNC political scientist Marc Hetherington and UNC global studies professor Jonathan Weiler, argue that worldviews — deeply ingrained beliefs about the nature of the world and the priorities of a good society — are fundamental to this political divide. The basic principle behind this is how individuals perceive danger.

In public opinion surveys collected during the 2016 presidential campaign, participants were asked to choose one of two statements:

- Our lives are threatened by terrorists, criminals and illegal immigrants and our priority should be to protect ourselves.

- It’s a big, beautiful world, mostly full of good people, and we must find a way to embrace each other and not allow ourselves to become isolated.

“Neither of these are right or wrong — they’re just different,” Hetherington says. “One side sees more threats, and if you see more threats then you have to protect yourself. The other side doesn’t see those threats in the same way so they perceive those actions as discrimination, not just protection.”

The results of the survey showed that nearly 80 percent of Donald Trump supporters chose the first statement, while nearly 80 percent of Hillary Clinton supporters chose the second. It’s important to note that the two statements didn’t ask participants about their political affiliation. This reveals how deeply ingrained worldviews are in our political identity and, therefore, why people have difficulty understanding how those on the other side see things.

In addition, Hetherington says, issues at the forefront of the political conversation in the mid-to-late 20th century were largely things like taxation, spending, and government regulation. Now, topics like racial and gender equality, sexual orientation, and climate change are high in public discourse — issues that are acutely tied to one’s identity and evoke strong feelings.

DURHAM- Lia Gilmore, a social worker, has noticed that political discussions have crept into her professional life.

“Normally, we would have more boundaries with our patients,” she says. “We wouldn’t talk about politics and get into that. But this is not politics— this is like good versus bad or dark versus light. And so, you end up crossing that boundary more and more because it’s so relevant to their everyday lives.”

Issues like racial equality, for example, didn’t previously divide parties so starkly, Hetherington says. Both parties were comprised of politicians with pro- and anti-civil rights sentiments. For the most part, that is not the case today.

“Things that divide us politically have changed,” Hetherington says. “If the partisan divide was about how much taxes we paid or how much is spent on highways, your identity wouldn’t be tied up much in that. Today our politics are all about these moral issues of right and wrong. We can’t help but look at ‘the others’ as flawed for not seeing the world in the same way we do.”

This moral conviction is of interest to UNC political scientist Tim Ryan. Through surveys and experiments, Ryan focuses on the underlying psychology in how people process political issues.

Abortion, minimum wage, healthcare, climate change — pick a topic in today’s political discourse and there are likely to be moral arguments in favor or opposed to it.

“Most issues, you will find some people who are morally convicted about it,” Ryan says. “On top of that, there aren’t many people we can find who don’t have any moral convictions whatsoever.”

In a 2015 to 2017 study, Ryan and colleagues at Stony Brook University asked participants what kind of bargains they would be willing to accept on a number of issues. Participants, paired with someone of the opposite political identification, would receive monetary compensation if they could reach a compromise they both found acceptable.

“We found that how much moral conviction is part of a bargaining exchange is predictive of bargaining failure,” Ryan says. “The more morality you have in a discussion, the more likely it is to hit a wall.”

This divide and way in which voters think about political issues didn’t come out of nowhere. To understand today’s state of polarization, one must look much further back in time.

A history lesson

From a historical perspective, a polarized society is typical. “People being at each other’s throats and big political divides — I think that’s, unfortunately, a normal state of being,” says Jason Roberts, a UNC political scientist who specializes in American political institutions.

An era that especially mirrors today’s political climate of strong, regionally-correlated party division is the late 19th century.

In the decades after the Civil War, the United States was divided on a number of contentious issues, the most obvious being slavery and racial equality. But those years also marked an increase in the rural-urban divide due to the country’s continued shift from a primarily agriculture society to a manufacturing, city-based economy.

“The country was changing,” Roberts says. “People felt left behind, they felt like their skills weren’t valued.”

People in cities looked down their noses at those in rural areas and people living in the countryside thought cities were dangerous, dirty, and overall unappealing, Roberts explains. Neither could understand the other’s way of life. Sound familiar?

The election of 1896 was sure to be contentious. Enter former Democratic Nebraskan senator, William Jennings Bryan.

Left: The presidential elections of 1896 and 1900 between William Jennings Bryan (left) and William McKinley were similar to today’s political climate. Right: During the 1896 presidential race, opponents of William Jennings Bryan created satirical coins ridiculing Bryan’s proposal of the free coinage of silver — a large, polarizing issue at the time (photo courtesy of the Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons and Cornell University/Wikimedia Commons).

“He was a strong populist focused on really invigorating society and making America great again, if you will,” Roberts says. “I’m not kidding. In many ways Bryan was not unlike Trump.”

The Populist Party, also known as the People’s Party, was a left-wing, agrarian party with a stronghold primarily in the Midwest and the South. Their main goal was promoting legislation that allowed farmers to compete more equally with big business and industry, and it was often critical of established politicians and other elites.

Known for his rousing speeches, Bryan was seen by his opponents as an ambitious demagogue and by his supporters as a champion of populist causes like the free coinage of silver, a national income tax, and the direct election of senators.

A prominent difference between Bryan and President Trump, though, is the result of their presidential race. In 1896, Bryan lost by a wide margin to William McKinley, 271 electoral votes to 176, and again in 1900 by 292 votes to 155.

Many political scientists see a large defeat as the only way to break polarization.

“It’s really gotten to be like a sporting event, like a big rivalry,” Hetherington says. “When the teams are close in terms of their ability, that intensity of competition just makes you hate the other side even more. It increases those feelings of identity that you have with your side and anti-identity you have for the other. If it’s a blowout then it doesn’t matter.”

MORRISVILLE- Victor Lindsey realizes that while he can have discussions with friends across the political aisle, many struggle with that task.

“It’s like sports, like a ‘my team versus your team’ kind of thing,” he says. “That’s why I think emotions are so tied to it. It’s just human nature— we’re tribal by default so we want to see our side win and bring in some kind of victory even if we’re not reaping any kind of reward other than ‘my guy won.'”

Take a UNC versus Duke University basketball game. The main driver for that rivalry is both teams are at the top of the league. Roberts recalls, on the other hand, attending a UNC versus NC State University game in which UNC fans chanted, “You’re not our rivals,” to the opposing team, rubbing salt in the wound of an already dismal defeat.

Democrats’ loss in 1896 and again in 1900 broke that polarization, sending them into the “political wilderness” to reevaluate their strategy.

Calm before the storm

The aftermath of the Great Depression and World War II marked a relatively quiet period in the realm of polarization in the United States. Roberts points to two factors in particular that may have aided in that. One was that parties were much more ideologically diverse compared to today and not so defined by partisan lines.

“You had Democrats who were more conservative than Republicans,” he says. “You also had Republicans who would be seen as quite liberal by today’s standards.”

Secondly, Republicans were losing elections. A lot of elections. Between 1933 and 1995, Republicans controlled Congress for only four years. They learned that if they wanted to get anything done, they had to work with Democrats.

That’s not to say that large, contentious issues weren’t mainstream. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 caused a rift among the Democratic Party. It is often noted as the moment when swaths of Southern Democrats changed allegiance, giving Republicans some traction and causing the two parties to redefine their ideologies.

Civil rights gains continued to struggle throughout the Nixon administration, on top of an already tumultuous time marked by the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal. Even so, Roberts says, there was comparatively little partisan voting.

“You had parties not taking drastically different positions on most of the issues of the day,” he says. “It was very common to have bipartisan compromises. Things that are politicized today were not politicized then.”

A prime example of this was when President Richard Nixon, a Republican, signed the Clean Air Act in 1970 and the Clean Water Act in 1972. In today’s world of partisan politics, it’s hard to imagine a Republican president signing such pivotal environmental protection legislation.

This bipartisanship couldn’t last forever, though.

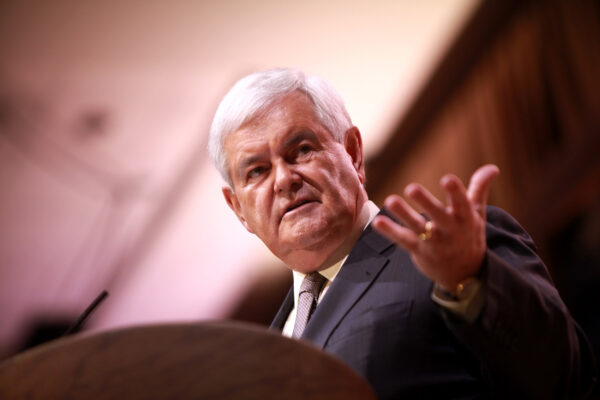

Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich speaks at the 2014 Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) in National Harbor, Maryland (photo by Gage Skidmore/Wikimedia Commons).

“I may be giving this person too much credit or blame — depending on your point of view — but I would say the father of modern political polarization is Newt Gingrich.” Roberts says. “No single person was more instrumental in what’s going on today than him.”

Gingrich, a professor from Georgia, won election to the House of Representatives in 1978 and served as House Minority Whip from 1989 to 1995. During that time, he led what is now called the “Republican Revolution.” Gingrich openly argued that in order to win, they had to be against everything Democrats were for — they had to vote “no” to every proposal and attack them at every possible juncture.

One of Gingrich’s more famous tactics was giving fiery speeches that railed against Democrats to an empty chamber, knowing that the newly installed C-SPAN cameras would allow his message to easily reach millions of voters throughout the country.

Gingrich began to recruit candidates and appoint people to committees based on their adherence to this strategic obstructionism instead of seniority and institutional loyalty, trying to push out more moderate Republicans. He also reframed policy debates as a fight between good and evil and politicized topics that were previously considered apolitical.

“From that point forward, if you weren’t loyal to the party leadership in Congress then you didn’t really get anywhere,” Roberts says. “That was a sea change from the ’60s and ’70s.”

Gingrich’s tactics were a success — he was widely covered in the media, liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats were losing elections and, with them, bipartisan cooperation was dwindling.

Democrats soon adopted the same strategy, blocking Republicans at every turn. “There’s a lot of research that shows that it’s whatever the parties are for becomes polarized,” Roberts says. “There aren’t many issues that are purely left or right so much as they get filtered through this partisan lens.”

Healthcare, Roberts explains, is a good example of this.

In 2003 with the support of Republicans, President George W. Bush signed legislation expanding Medicare to cover prescription drugs. Democrats were in opposition. Fast forward to the Affordable Care Act in 2009 — a bill that contained market-based ideas from conservative think tanks in reaction to President Bill Clinton’s failed healthcare plan. Republicans were against it.

“That’s not about the issue being ideological. That’s about the parties making it political,” Roberts says. “It’s not that they disagree on the principle behind it, they disagree because the other team is for it.”

SANFORD- Mary and Tom Douglas are on opposite sides of the political divide. While they disagree on many issues, they both think polarization among political leaders has increased over the years.

“There was not that much division years ago,” says Tom, who supports Joe Biden. “I think we’ve gotten to the point where the leaders we have got us into this train of thought that’s ‘You need to see it my way or the highway.'”

“Honestly, for the last several presidents that we’ve had in there, the Republicans and Democrats do not work together,” adds Mary, who says she will be voting for Donald Trump. “They’re just against each other. When Obama was there, the Republicans were totally against him and did not agree on anything. Now the Democrats are that way with Trump.”

This phenomenon, Hetherington says, is called negative partisanship.

“In a lot of ways, political motivation right now isn’t about what one’s own side might accomplish,” he says. “We’re motivated by stopping the other side from what they’re trying to accomplish.”

In a 2013 study, Ryan examined compromise in the realm of politics. Participants could receive up to $4 if they were willing to let a payment be made to an opposing political organization, a group called “The Tea Party Patriots” or the “Progressive Change Campaign Committee.”

“I was trying to capture the idea of whether you are willing to allow your political adversary to benefit in order for you to benefit,” Ryan says. “In one sense, this is the essence of compromise — you’re going to be better off but you have to let the other person be better off too.”

The study results mirrored congressional gridlock: 65 percent of those opposed to the Tea Party group and 44 percent of those opposed to the progressive group chose not to receive any money in order for their adversary to be left empty handed as well.

While successful in gaining seats, many argue this tactic of anti-partisanship has come at a cost to congressional productiveness and ultimately, the American people. It also instilled an angry, combative, and tribal attitude that has since trickled down to voters.

“I would say that elite polarization has created mass polarization,” Roberts says. “The fact that the Democrats and Republicans in Washington are so different from one another now is what has led the public to be that way. The public didn’t wake up one day and say, ‘We want the world to be more polarized.’ We were led to that by the elites.”

Where do we go from here?

Before unfriending your sister-in-law on Facebook or canceling dinner plans with your parents, take a step back, says Hetherington. And while you’re at it, McGregor advises to stop doom scrolling too.

“We’re far apart on how we feel about each other. What media, especially social media, does is it fuels those negative feelings. It gives you the outrage of the day — or the outrage of the hour, these days,” Hetherington says with a laugh. “Maybe scaling back from that a little bit will preserve both your mental health and feelings about your fellow man.”

He encourages political participation and news consumption, but cautions against constant monitoring via social media or traditional outlets.

While high polarization has negatively affected the country, it has positively impacted voter turnout.

As of October 25, over 58 million Americans had already cast their ballot — either by mail-in or early in-person voting. With just over a week left before the election, that number has already surpassed 2016 early ballot numbers. While the pandemic has a large part in this phenomenon, it’s not the only factor.

“Everybody talks about the negative side of polarization, and with good reason. But polarization has at least a few positive consequences,” Hetherington says. “One of them is that it allows people to really see the differences that exist in their choices and encourages them to participate at much higher rates. Polarization increases that anger or enthusiasm — all those action-emotions we have — and increases voter participation.”

Take the women’s suffrage or civil rights movements. Both are examples of eras of contentious issues in political discourse.

“You know, maybe if we didn’t have that polarization then the political system would have ignored those concerns,” he says. “In other words, the things that made the system polarized, these hot-button issues, were well worth it.”

Americans can only hope that something good can come out of this divisive time and, someday, will look back and say: “It was worth it.”