At the corner of 5th Avenue and East 91st Street in Manhattan’s Upper East Side sits the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. A colorful exhibition featuring familiar designs by Susan Zuzek — the textile worker behind many of the bright, floral prints that make up the iconic fashion brand Lilly Pulitzer — adorn the walls. It is common for textile workers to remain anonymous, but this exhibition strives to give Zuzek the credit she’s due.

Deeper in the archives of the Cooper Hewitt, though, are two samples of hand-woven yellow-and-white thread that are broadly attributed to the New York Guild of Hand Weavers. A hand-drawn pattern penned out on graph paper accompanies each of the samples — instructions for a future weaver who may want to recreate the diamond designs for themselves. If you look hard enough, you can see a name signed and dated on the bottom: “Olive Risch.”

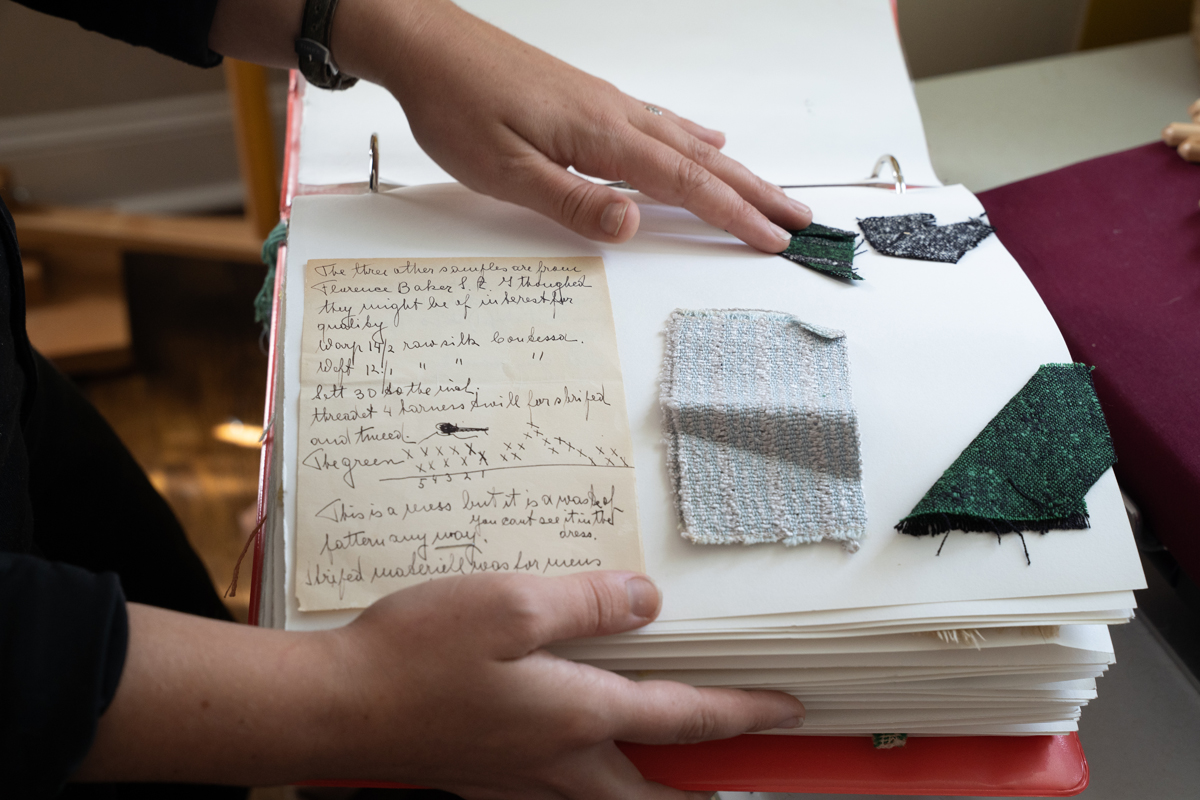

More than 500 miles away, Danielle Burke pulls a binder off a shelf lined with volumes of art, textiles, and oral histories in her home studio in Carrboro. She flips it open to reveal a swatch of the same hand-woven sample of yellow-and-white thread accompanied by an aged piece of paper filled with Risch’s protracted handwriting.

“I could trace her work in institutional archives because I know her — I have a record of it — but the actual archive goes unnamed like she’s not there. None of those women in her guild are named either,” Burke says. “So where did that attribution go, and how do we recognize people’s labor?”

Burke is a master’s student of Folklore within the American studies department. She’s interested in the role material objects play in telling the story of the individuals who make them and the communities they belonged to.

“I just think there’s a lot of craftspeople that live in that world and have been unexamined,” she says. “Olive is one way to start looking at that.”

Combining studio art with archival and ethnographic research, Burke is learning to weave and piecing together what life might have been like for Risch and the women in her handweaving and lacemaking guilds from the 1950s to the ’70s.

Burke flips through the binder she transferred the samples of woven swatches and hand-written notes into when the hat box that originally held them began to fall apart. (photo by Elise Mahon)

Unboxing Olive

Following her undergraduate studies, Burke was named a Windgate-Lamar Fellow by the Center for Craft. She spent five years of fieldwork researching traditional coverlet weaving — a specific way of making blankets — in Western North Carolina, collecting the oral histories and techniques of people in the Appalachians who had learned from the generations of weavers before them. She soon fell in love with the practice and began looking for a loom of her own.

She found one in New York City, where a woman was selling her entire weaving studio, and was able to purchase it with the help of her fellowship funds.

“This loom is a workhorse. It’s like the truck of looms,” she says. “A pretty standard loom has four harnesses, but this has 12. The more harnesses you have, the more computing power and complex weave structures you can make.”

When Burke showed up with her U-HAUL to take it back down the coast, the woman kept offering her other tools and throwing boxes of samples and patterns in the back along with it. Among them was an inconspicuous hat box, falling apart from age and the weight of its contents.

“It was completely unorganized and just filled with woven swatches and pieces of paper,” Burke says. “It was the original loom owner’s, and I realized I had this sliver of this woman’s personal archive.”

The original loom owner, of course, was Olive Risch. Risch grew up on a farm in Upstate New York in the late 1890’s, went on to earn a degree in English by 1918, and became a teacher. She lived through the beginning of women’s suffrage, World War I, and the country’s bicentennial, making her an interesting case study.

Burkeʼs most recent weaving project is a narrow strand of orange-and-white thread in the pattern of the mRNA sequence that makes up the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. (photo by Elise Mahon)

“Olive was a part of an upper middle class, privileged landscape of people,” Burke explains, her eyes lighting up with every new layer she shares about Risch’s life.

Risch only worked as a teacher for a few years before secretly marrying her husband who was a doctor at City Hospital in Manhattan, now called Charity Hospital. At the time, it was both socially unacceptable and against the rules of the school where she taught for her to be married and continue working. So, soon after marrying, she had to find other ways to spend her time.

“It’s interesting that employed work would be seen as wrong, but sitting at a loom was a respectable use of time,” Burke says.

Folklore is an inherently communal practice, passing down traditions, stories, and cultural knowledge from person to person. The nature of Risch’s weaving fits perfectly into this framework. Olive was not the only woman pursuing this pastime. There were guilds full of other handweavers and lacemakers of which she was an integral member.

Burke is currently working with and learning from the contemporary handweaving and lace guild — as well as Olive’s granddaughter —to piece together and contextualize the broader historical narrative.

“I can’t interview any of the women that she did this work with,” Burke says. “But I can see what stories are maintained in the guild from that era and get to know that time and place through contemporary storytelling. People still talk about Olive and her friends, so their expertise has been simultaneously remembered and forgotten.”

Lessons from the loom

For Burke, it all comes together when she sits at the loom, weaving together both the physical threads and bits of character she finds in Risch’s old, handwritten notes.

A portion of the Modern vaccineʼs mRNA strand that Burke has translated into a pattern to weave on her loom. (photo by Elise Mahon)

“I don’t feel like it’s me alone in the space. It’s me and Olive and other people that Olive knew,” Burke says. “Looking at her life and seeing how much of it was spent sitting at this loom just like I am, and sort of questioning what it means to embody that similar space, but 70 years apart.”

Her most recent project is a narrow strand of orange-and-white thread 27 yards long, in the pattern of the mRNA sequence that makes up the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine.

“We’re always surrounded by cloth, and we have been for a very long time. It’s so mundane and ordinary, but it’s quite a process to make and be a part of,” she says.

She described weaving as a sort of magical chaos — an experience that has helped her reflect on life, the space, and time that she occupies.

“There’s a lot of metaphors of life that I see in weaving,” she says. “When you’re setting up the loom, you’re moving hundreds of threads around, and you have to untangle them constantly. You fabricate chaos to then put it all back in order, and the loom helps you do that by organizing and keeping and releasing tension.”