After a short boat ride across the Oscar Shoal, near Harkers Island in Beaufort, a team of marine scientists arrive at their field site. They zip up wetsuits and strap on weighted belts and snorkels, as if preparing for a deep dive — but they are conducting their seagrass fieldwork in just a few feet of water.

“Generally speaking, seagrass is right up there at the top for the best habitat for a lot of the marine critters we care about,” says Joel Fodrie, a UNC marine scientist.

Seagrass plays a significant role in supporting populations of many coastal commercial fisheries in North Carolina like blue crab and snapper. As a safe place for both eggs and juvenile species, it is often used as a nursery habitat. The structural complexity of seagrass benefits both predators and prey, serving as a great hiding place within the beds, as well as a rich foraging area for predators along the edge. The grass also slows water flow, making it easier for filter-feeding species like scallops to feed in the water column.

Some grass species go beyond helping fish populations, Fodrie explains. They can also stabilize sandy shoals, clear pathogens from the water, and capture carbon.

The team is installing Artificial Seagrass Units (ASUs) to identify what type of seagrass structure — continuous or fragmented — marine life prefer. In 2018, members of the Fodrie lab spent about eight months creating around 2,500 ASUs, each one square-meter in size. To mimic natural seagrass, they tied green ribbon to sturdy, plastic mesh, and installed them in the shoal in a variety of designs. Over the course of about five months, weather permitting, the team will set minnow traps weekly and collect them for analysis after 24 hours, noting which species of marine life have taken root in the artificial habitats.

An artificial seagrass unit lies on the boat before being installed in the water. This year’s experiment uses over 760 units.

An artificial seagrass unit lies on the boat before being installed in the water. This year’s experiment uses over 760 units.

Amy Yarnall, a UNC PhD student, installs an artificial seagrass landscape. There are 16 of these in the shoal, each containing 48 ASUs. The difference between each is in its design, ranging from one large, continuous seagrass patch to many, fragmented patches.

Amy Yarnall, a UNC PhD student, installs an artificial seagrass landscape. There are 16 of these in the shoal, each containing 48 ASUs. The difference between each is in its design, ranging from one large, continuous seagrass patch to many, fragmented patches.

The team spent four days installing seagrass beds, with each site taking up to two hours.

The team spent four days installing seagrass beds, with each site taking up to two hours.

Students joke while grabbing supplies to install ASUs.

Students joke while grabbing supplies to install ASUs.

Research tech Grace Roskar organizes lawn staples used to pin down ASUs in the water. Over the past two years, Fodrie’s lab has put in thousands of hours of work into the seagrass project. With additional help from volunteers, he estimates they have spent up to 6,000 hours for construction of the ASUs alone. “We try to do things at pretty ambitious scales,” he says. “Ecologists are sometimes limited by logistics, but we tend to pull off experiments at the scales that we think matter and not necessarily the scales that logistics may lean toward.”

Research tech Grace Roskar organizes lawn staples used to pin down ASUs in the water. Over the past two years, Fodrie’s lab has put in thousands of hours of work into the seagrass project. With additional help from volunteers, he estimates they have spent up to 6,000 hours for construction of the ASUs alone. “We try to do things at pretty ambitious scales,” he says. “Ecologists are sometimes limited by logistics, but we tend to pull off experiments at the scales that we think matter and not necessarily the scales that logistics may lean toward.”

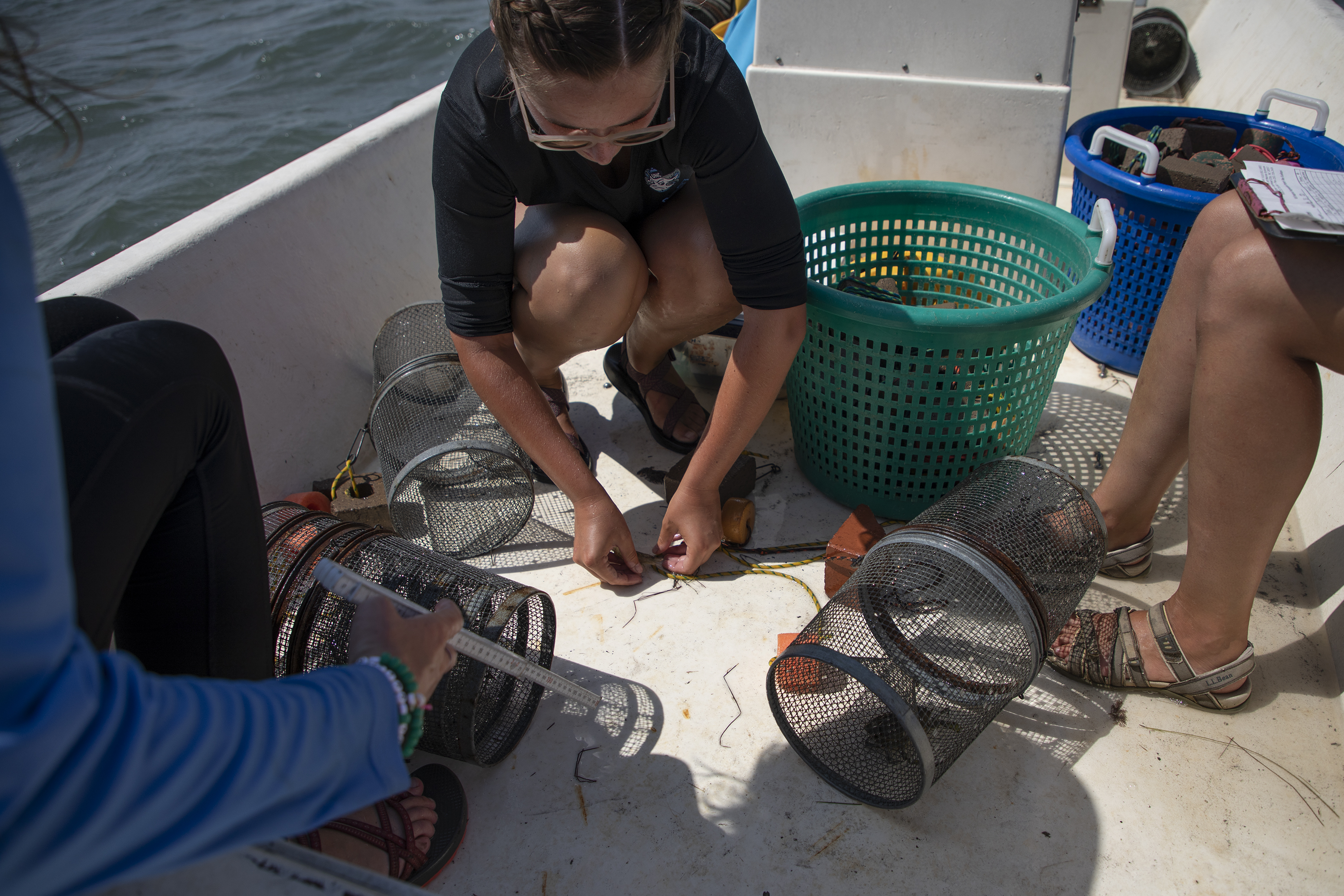

It’s mid-July in Beaufort, and the temperature is nearly 100 degrees. Research techs Savannah Swinea and Jade Danford-Klein hop out of the small boat, happy to cool down. After pulling up minnow traps from the seagrass landscape, they wade back to the boat with their catch in tow. Onboard, they unhook and dump the traps, peering over at what surprises are in store.

It’s mid-July in Beaufort, and the temperature is nearly 100 degrees. Research techs Savannah Swinea and Jade Danford-Klein hop out of the small boat, happy to cool down. After pulling up minnow traps from the seagrass landscape, they wade back to the boat with their catch in tow. Onboard, they unhook and dump the traps, peering over at what surprises are in store.

Danford-Klein, a UNC junior studying biology and marine science, holds out a female blue crab carrying an egg sack on her underbelly before releasing her back in the water. The team finds a variety of small marine life on their excursions such as pinfish, swimming crab, pig fish, and black sea bass.

Danford-Klein, a UNC junior studying biology and marine science, holds out a female blue crab carrying an egg sack on her underbelly before releasing her back in the water. The team finds a variety of small marine life on their excursions such as pinfish, swimming crab, pig fish, and black sea bass.

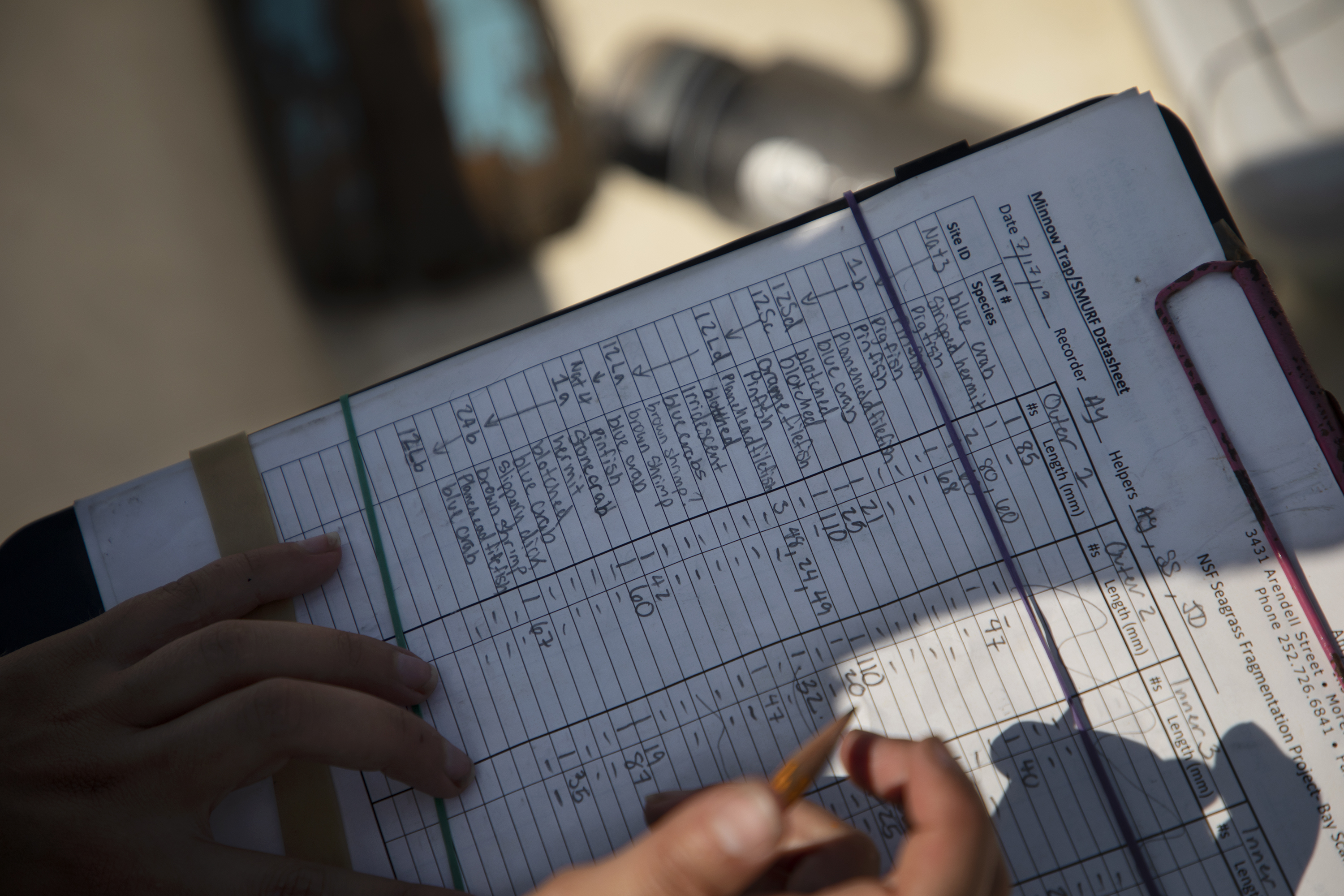

Yarnall logs data on fish, crab, and shrimp found in the traps including the species name, number of each specimen, size, and whether they were caught centrally within the seagrass bed or in the outer edge.

Yarnall logs data on fish, crab, and shrimp found in the traps including the species name, number of each specimen, size, and whether they were caught centrally within the seagrass bed or in the outer edge.

Swinea measures a specimen while Yarnall takes notes. The group gathered four minnow traps at each site — two within the bed and two on the outer edge — totaling 32 traps in all.

Swinea measures a specimen while Yarnall takes notes. The group gathered four minnow traps at each site — two within the bed and two on the outer edge — totaling 32 traps in all.

Preliminary results from last year suggest that larger, patchier landscapes support more animals and greater biodiversity. This could be because patchy seagrass beds incorporate two types of habitat — seagrass and sand flats — Yarnall explains.

Preliminary results from last year suggest that larger, patchier landscapes support more animals and greater biodiversity. This could be because patchy seagrass beds incorporate two types of habitat — seagrass and sand flats — Yarnall explains.

“Perhaps having both habitats interspersed leads to more species being able to use one type of habitat or both, depending on their preferences or particular needs at that time,” she says. “The dichotomy between those two habitats seems to, in some cases, increase diversity.”