More than a decade ago, Michelle King had her first child. Responsibilities like cleaning, caring, and soothing a newborn consumed her days. But King still remembers that all she wanted to do amidst the chaos was cook Chinese food for her daughter — like her mom did for her.

While thumbing through a cookbook passed down by her immigrant mother, some of the pages stuck to her fingers: It was the first volume of Taiwan TV chef Fu Pei-Mei’s culinary guides.

As she flipped through the book, she noticed more than recipes beneath the binding. There were photos of Fu traveling the world, shaking hands with VIPs, and teaching cooking classes, as well as newspaper clippings praising her accomplishments in the media and the kitchen.

“As a historian, when I saw the pictures and clippings, I knew there was a paper trail and thought maybe there’s something to write about,” King says. “But I didn’t honestly know anything about her.”

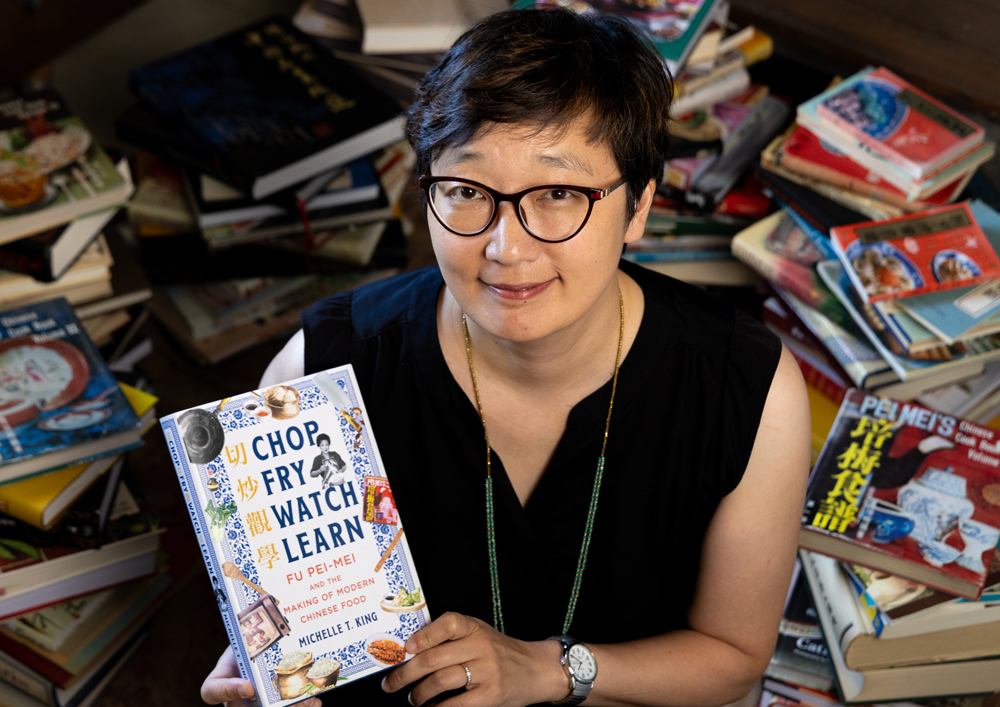

King is a professor of Chinese history and gender studies at UNC-Chapel Hill. Her newest book — “Chop, Fry, Watch, Learn” — hit shelves May 7, 2024. It represents a decade of King’s research into the life and legacy of culinary icon Fu. She collected stories from translators, family members, and people who were changed by the Chinese star.

In a way, Fu Pei-Mei is Taiwan’s equivalent of Julia Child, a famous TV chef from the 1960s who brought French cuisine to the masses in the United States. Fu did that for Chinese cooking in Taiwan and Japan.

“I use her as that benchmark, so people have some idea of what the heck I’m talking about,” King explains. “But I want people to upset their notions of primacy. Fu Pei-Mei was on television before Julia Child, by a few months.”

Fu stayed on TV continuously for 40 years, wrote over 30 cookbooks, and traveled all over the world. She set a standard for an entire generation of Chinese and Taiwanese women — from Chinese mainlanders who fled to Taiwan during the formation of the People’s Republic of China to migrants who left Taiwan for other countries in search of opportunity.

In any case, most readers of Fu’s cookbooks were searching for a taste of home.

Cooking up context

Fu passed away in 2004, and when King began researching her life in 2014, she didn’t know anyone who’d met the cooking icon. But then, during a trip arranged by the Taiwanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, she happened to sit next to a government official who knew Fu’s younger daughter — and that she was living in Florida.

King reached out to her immediately, and then got connected to Fu’s older daughter and son, who still live in Taiwan.

“And then I could interview,” King says. “Suddenly, I had access to her story and learned more about her through them than I could have otherwise.”

Fu was born in mainland China in 1931 and moved to Taiwan in 1949. King’s book uses historical moments — from advances in kitchen technology to women’s roles — to broaden the reader’s scope of Fu’s fame amidst a larger geopolitical conflict between China and Taiwan.

Between 1962 and 2002, Fu Pei-Mei hosted a series of cooking shows on Taiwan Television and presented more than 4,000 Chinese cuisine dishes. (photo courtesy of An-chi Cheng & Michelle King)

During the Chinese civil war, Mao Zedong created the People’s Republic of China on the mainland, causing over 1 million people to flee to Taiwan, including Fu. These refugees went on to become the dominant socioeconomic class in Taiwan and had incredible political and financial sway. King includes these inequalities in her pages.

While the book focuses on Fu’s incredible story of stardom and eventual independence from her husband — which, for that time, was unheard of — it also educates readers on the lesser-known culture and history of Taiwan.

“I think my perspective as a historian brings a context and a deeper perspective. It’s not just a biography — it uses her life to talk about these other things.

“I’m really lucky,” King adds with a laugh. “The beautiful thing is, that when you talk about Fu and when people who know her remember her, the stories just come out.”

Sometimes her luck sent her chasing information cross-country. Like in North Dakota, where she tracked down and interviewed a son of one of Fu’s Chinese-to-English cookbook translators.

But many times, King’s work drew her back to Taiwan, where her parents were from. Her mother taught herself how to cook after she moved to the U.S. in the 1960s — using, of course, Fu’s cookbooks.

“This woman publishing bilingual cookbooks in this Cold War period means she’s making a statement, claiming she can speak to two entirely distinct and different audiences,” King says. “She’s speaking to housewives in Taiwan and Americans who are stationed there, to Americans in the United States, and to Chinese Americans who only read English now.”

King also includes stories from her mother, aunts, and family friends — women from the 1940s who belong to the same generation as Fu — throughout the book.

“It was really important to me that it’s not just the biography of a famous person, but that it illuminates the significance of food in women’s and family’s lives,” King says.

Slicing Taiwanese socioeconomics

In 2020, a UNC School of Nursing professor named Ya-Ke “Grace” Wu contacted King after reading an Endeavors article about her earlier Fu research.

“I reached out immediately to thank her for her contribution on this topic,” Wu says. “And I felt a bit homesick to see someone tell the story about this lady I watched when I was a child.”

King immediately responded with thanks — and a request for Wu to be interviewed for her book.

Wu told King about her chaotic childhood in Taiwan. Her father spent time in jail, and her mother and siblings cleaned houses. Whenever Wu finished school, she knew she’d come home to an empty house. To feel a little less lonely, she’d turn on the TV and watch Fu Pei-Mei.

But up until she’d read the article about King, Wu hadn’t thought of Fu in years.

“There’s always been this battle between the original Taiwanese people and the mainlanders,” Wu explains. “And I didn’t know this when I was a child, that this battle exists, but what I did know was the discrimination I received as a child in extreme poverty.”

Wu is a native Taiwanese, unlike the Han Chinese mainlanders who emigrated from China to Taiwan in 1949 and dominated the country’s socio-political culture from the 1950s to the 1980s.

She left her home to go to nursing school and spent the next two decades working as a registered nurse, then as a lecturer in Taiwan. In 2013, she moved to the U.S. to study nursing and has taught at Carolina as an assistant professor since 2020.

While she hasn’t been back to Taiwan in over 10 years, she still cooks a mean Taiwanese stir-fry for her husband every week.

“When Grace told me all of this I cried, because I could not believe what this woman had done with her life and even how her story intersects with Fu Pei-Mei’s,” King says.

Wu cemented why King needed to include all these other voices. That the decade of research she’d done wasn’t to place Fu on a pedestal alongside the 4,000 glorious dishes she’d made.

“What is amazing about this book is that it captured a very complex relationship between Taiwan and China,” Wu says.

For King, this story was about the power of television, food, identity, and joy — and most importantly, people.

“The kitchen is a weird space,” King explains. “On the one hand, it’s entirely domestic, and we think of it as a woman’s space or gendered space. But on the other hand, some women took it into the public and made an entire career out of these domestic tasks that they were basically obliged to do. It’s just fascinating.”