What happens to paintings between the time they leave an artist’s hand and arrive on the wall of a museum? Turns out that, like people, they change throughout their life cycle. They age, become damaged, are painted over — all of which may change their original essence. Then, once in the hands of the museum, they may undergo all sorts of scientific analysis and conservation efforts to attempt to discover and understand what is left of their original form.

Evidence suggests that the Ackland Art Museum’s “Portrait of a Young Lady” has led an interesting life. Though the painting was probably commissioned by an aristocratic, 16th-century German family, it traveled in and out of private collections until the Ackland purchased it in 1968. Not only has it been severely damaged and restored multiple times, but recent analysis shows intentional cracking or aging throughout and that the date and family crest are 18th– or 19th-century additions — all changes that have taken the painting farther and farther away from its original appearance.

“A painting like this presents the opportunity to bring together art historians, conservators, and scientists interested in the burgeoning field of the technical study of art,” says Peter Nisbet, the Ackland’s deputy director for curatorial affairs. “It’s proved to be less an important example of Bruyn’s portraiture of nearly 500 years ago, and more a case study in the life of an object, undergoing so many alterations and ‘improvements’ as to almost become a different picture.”

Brianna Guthrie, an art history PhD student at Carolina, agrees. “It’s an excellent example of how technical analysis can inform traditional scholarship,” she says. “Testing and imaging will help us answer some of the most basic — and vital — questions about the painting like who, where, how, and why?” The Ackland’s 2017 Joan and Robert Huntley Scholar, Guthrie participated in the beginning of this extensive research project, helping unravel the mystery behind the “Portrait of a Young Lady’s” life.

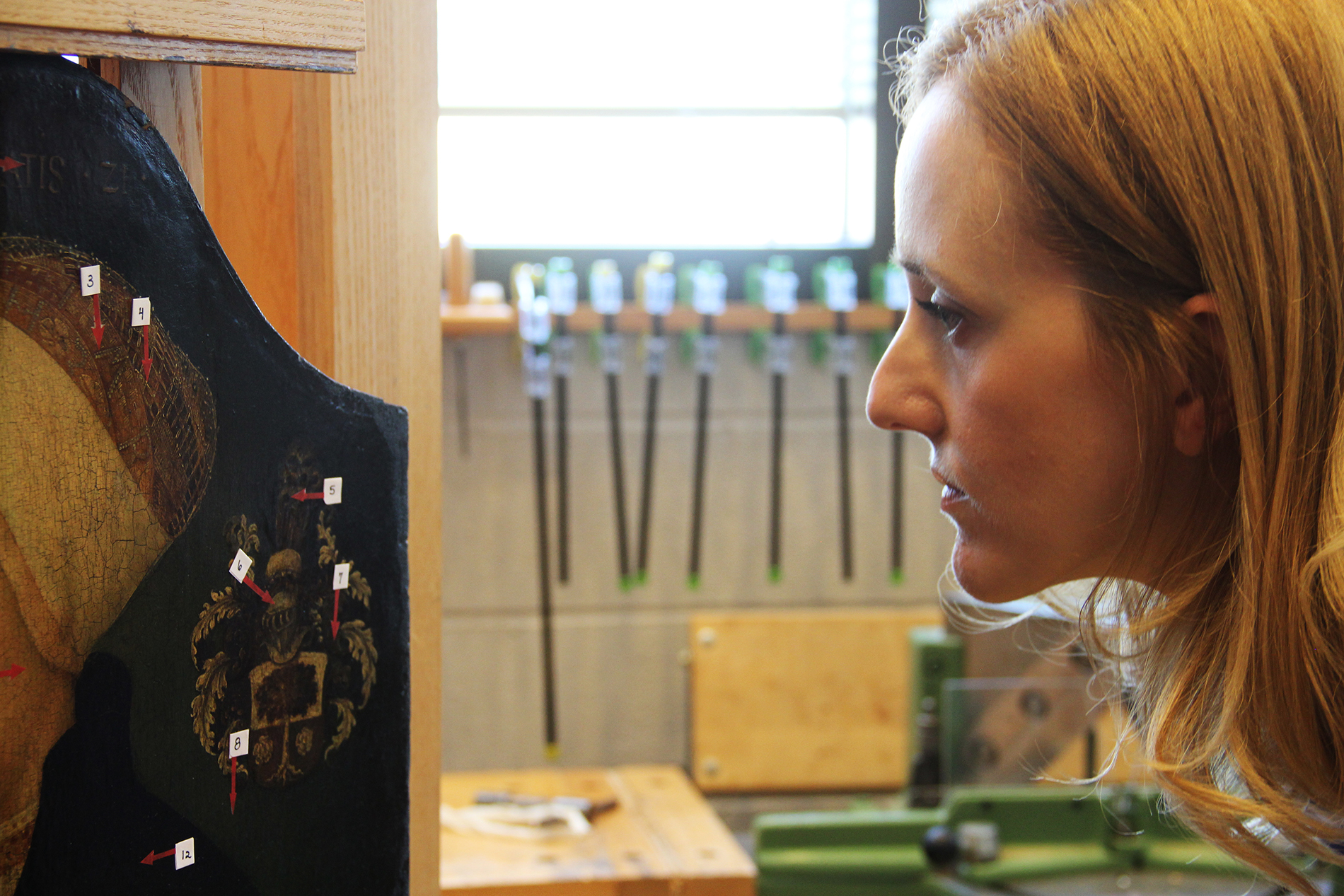

Once Brachmann pulled the painting from the Ackland’s storage, the museum invited several art historians and experts on 16th-century German paintings to view the piece. After brief examination and discussion, the museum decided to pursue further study on the picture to determine attribution and its condition under the varnish. Here the painting rests on an easel in Ruth Cox’s studio (right). Cox is a private conservator in Durham who worked with the Ackland on this project.

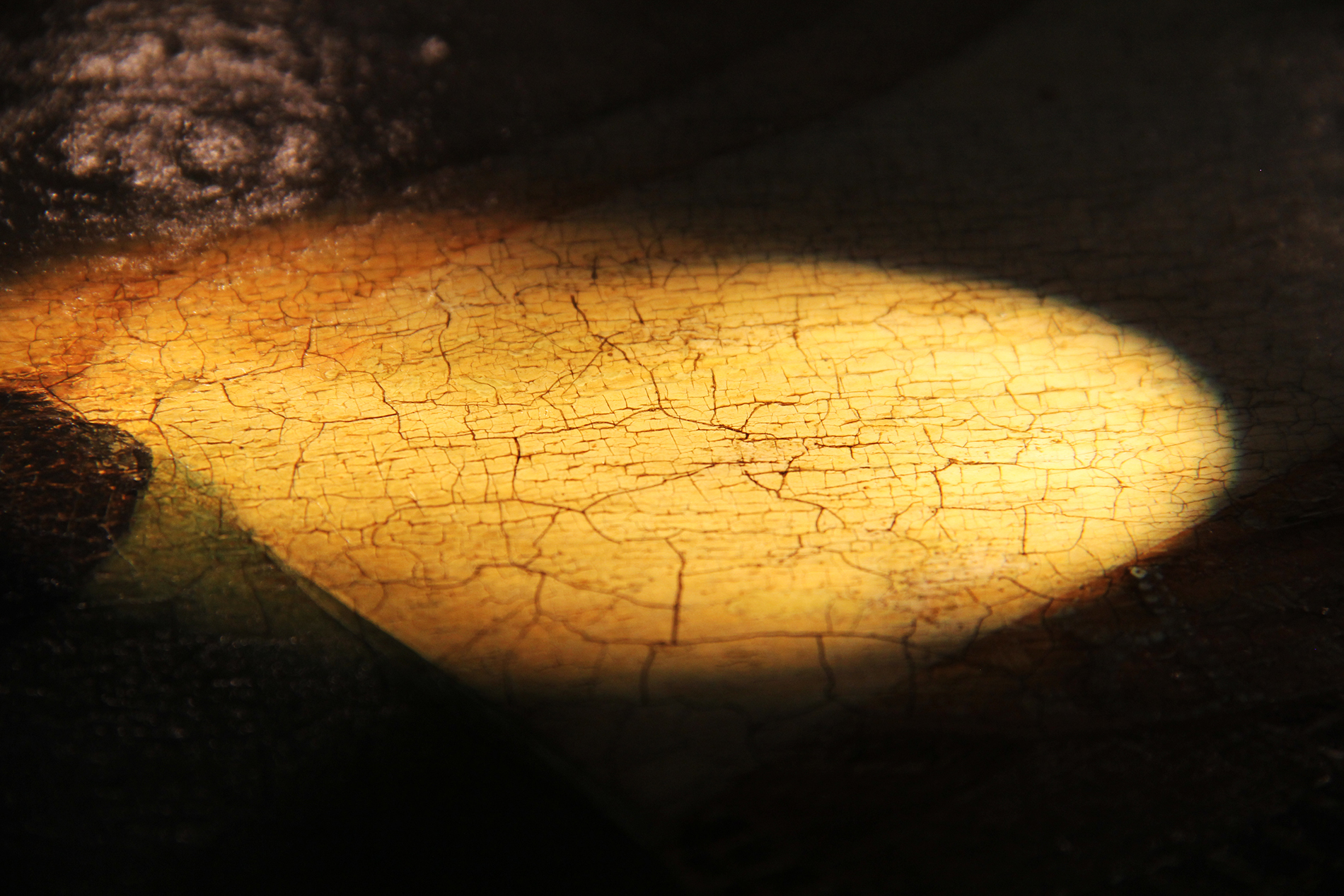

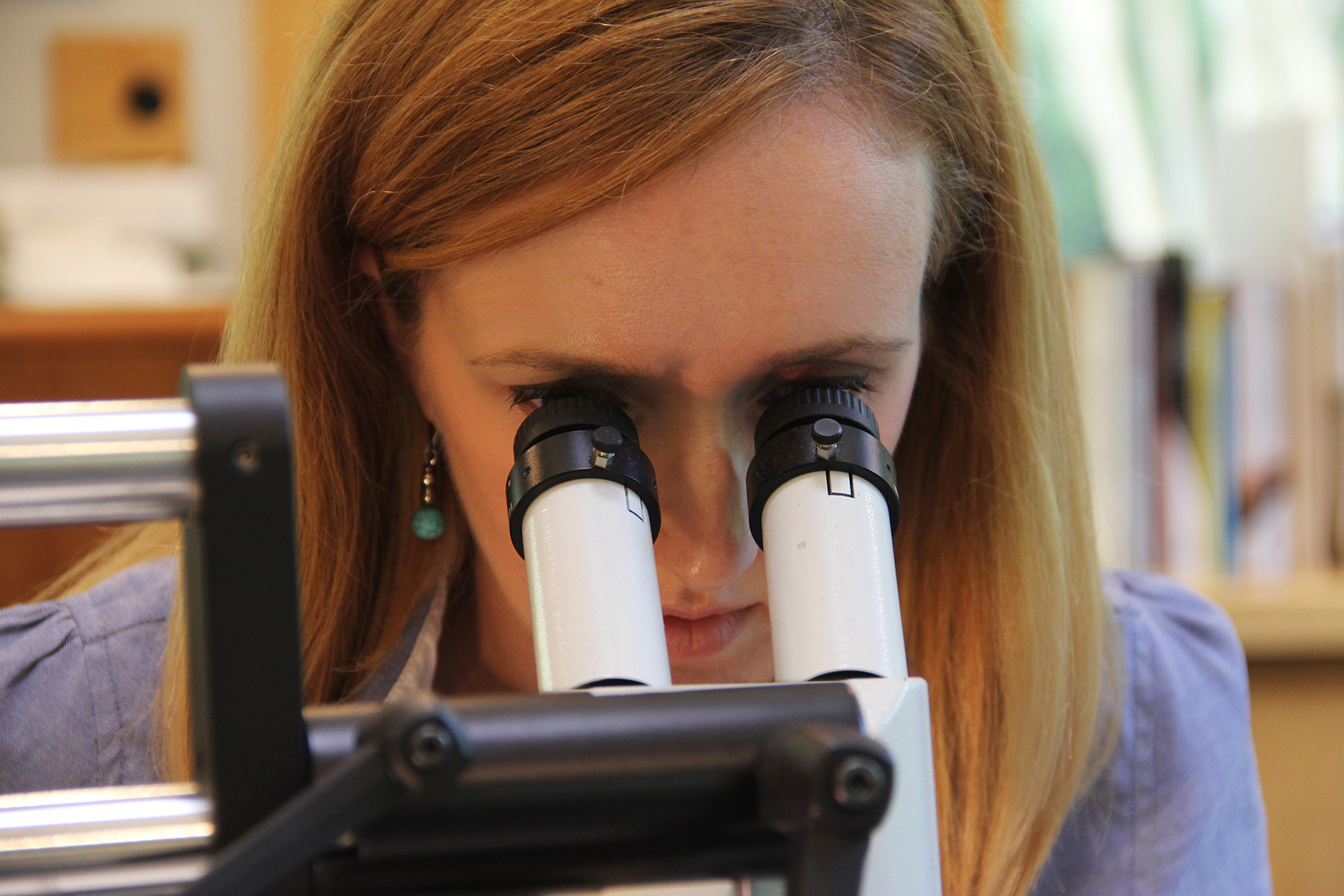

Cox and Guthrie examine the portrait using a binocular microscope. The area illuminated by the microscope’s fiber optics shows damaged paint with both the original and restorer’s craquelure — a network of dense cracking in the paint.

Although age cracks in the paint are expected for a painting this old, some of the black “cracks” visible are not true fissures in the paint and ground layers. After thorough microscopic examination, Cox determines that the heavy black lines are actually a previous restorer’s ink, which floats within the varnish layer. They were most likely made using a quill or fountain pen. Beneath the varnish sit the true paint and gesso cracks, which are much finer and clearly visible under magnification.

Guthrie is the fifth recipient of the Joan and Robert Huntley Scholarship, which gives UNC art history graduate students the opportunity to conduct research using collections and resources from both the Ackland Art Museum and the North Carolina Museum of Art. Robert Huntley, a professor and physician who helped found the UNC Department of Family Medicine, had a deep appreciation for the arts. He passed in 2002 and, his wife — herself an art lover and Carolina alumnus — endowed the scholarship in 2012.

Cox uses ultraviolet (UV) illumination to reveal surface anomalies on the painting. The lamp, which produces a consistent 365-nanometer wavelength of light, helps identify the use of various varnishes and retouching — all of which fluoresce or absorb the light to varying degrees.

A conservator like Cox not only uses analytical tools to answer questions about paintings, but also completes the hands-on work of stabilizing physical insecurities, removing old varnishes and restorations and compensating for losses in the original paint film. This cart in her studio stores paints and mediums, tools for leveling fills, tweezers for removing stray bits of cotton and debris, a silk for polishing surfaces, and several varnishes. “All restoration paints are reversible without damaging the original paint,” Cox explains. The possible Bruyn, she points out, has paint from previous restoration that was not applied following modern ethics in conservation. If the Ackland decides to conserve it, layers of old varnish and retouching will be removed, and losses filled and inpainted.

Bill Brown, chief conservator at the North Carolina Museum of Art (NCMA), explains the different analyses used to examine the painting. After Cox completed her in-depth observations, the painting was moved to the NCMA, where museum conservators and Washington and Lee University chemist Erich Uffelman and his students begin the instrumental investigation.

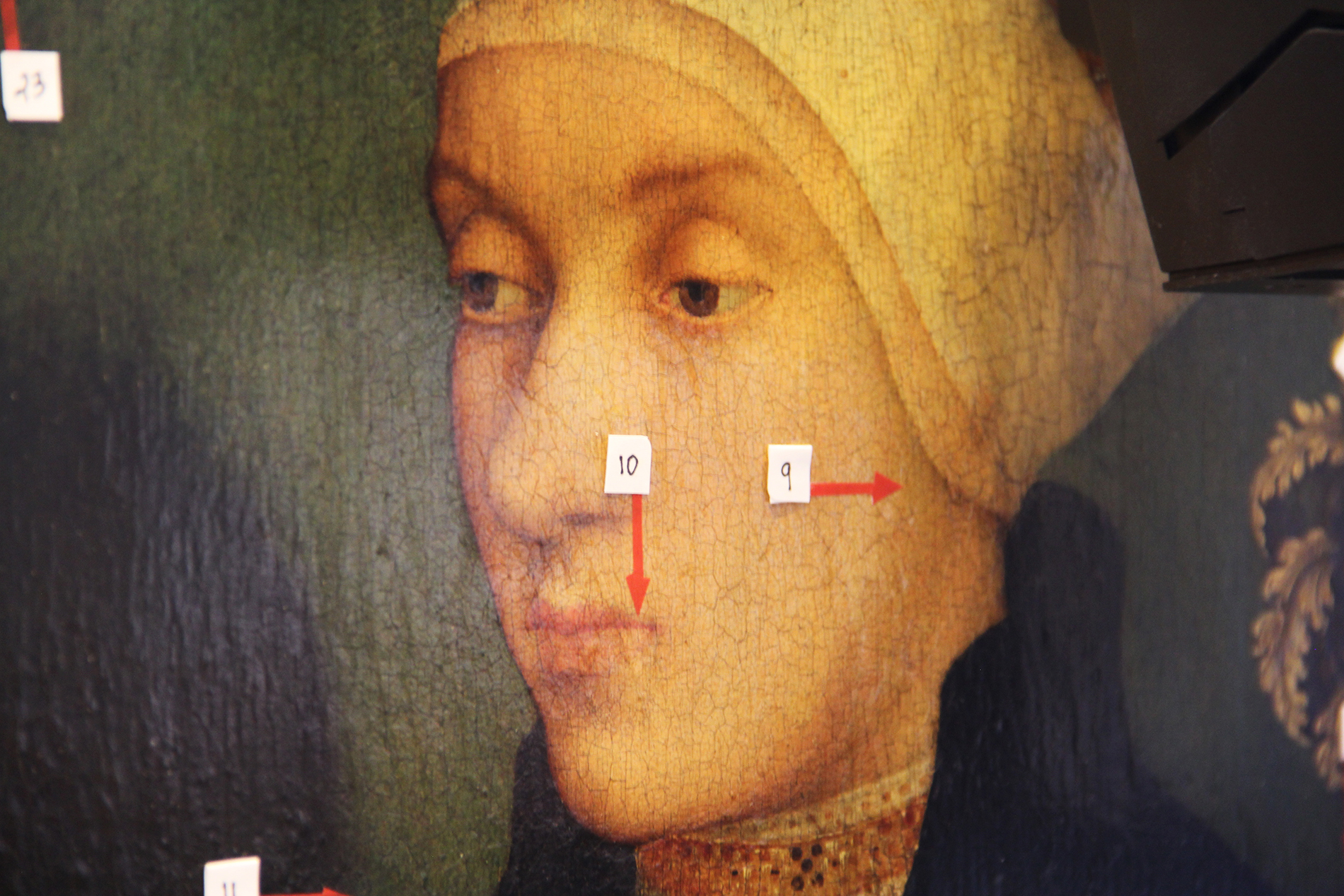

NCMA Conservator Perry Hurt adjusts an Elio X-Ray Fluorescence (pXRF) instrument, which helps determine elements in certain areas of the painting. Revealing these elements within the paint informs art historians and conservators about the timeframe in which a particular paint layer was made. More modern pigments include elements like zinc and chromium — the finding of which in an older artwork suggests over-painting or restoration. Older pigments contain elements like copper, iron, and lead.

Markers placed throughout the painting identify areas to sample using the pXRF instrument. The spectra produced by the machine require the expertise of a scientist to interpret, the data from which must be checked against other data collections for accuracy.

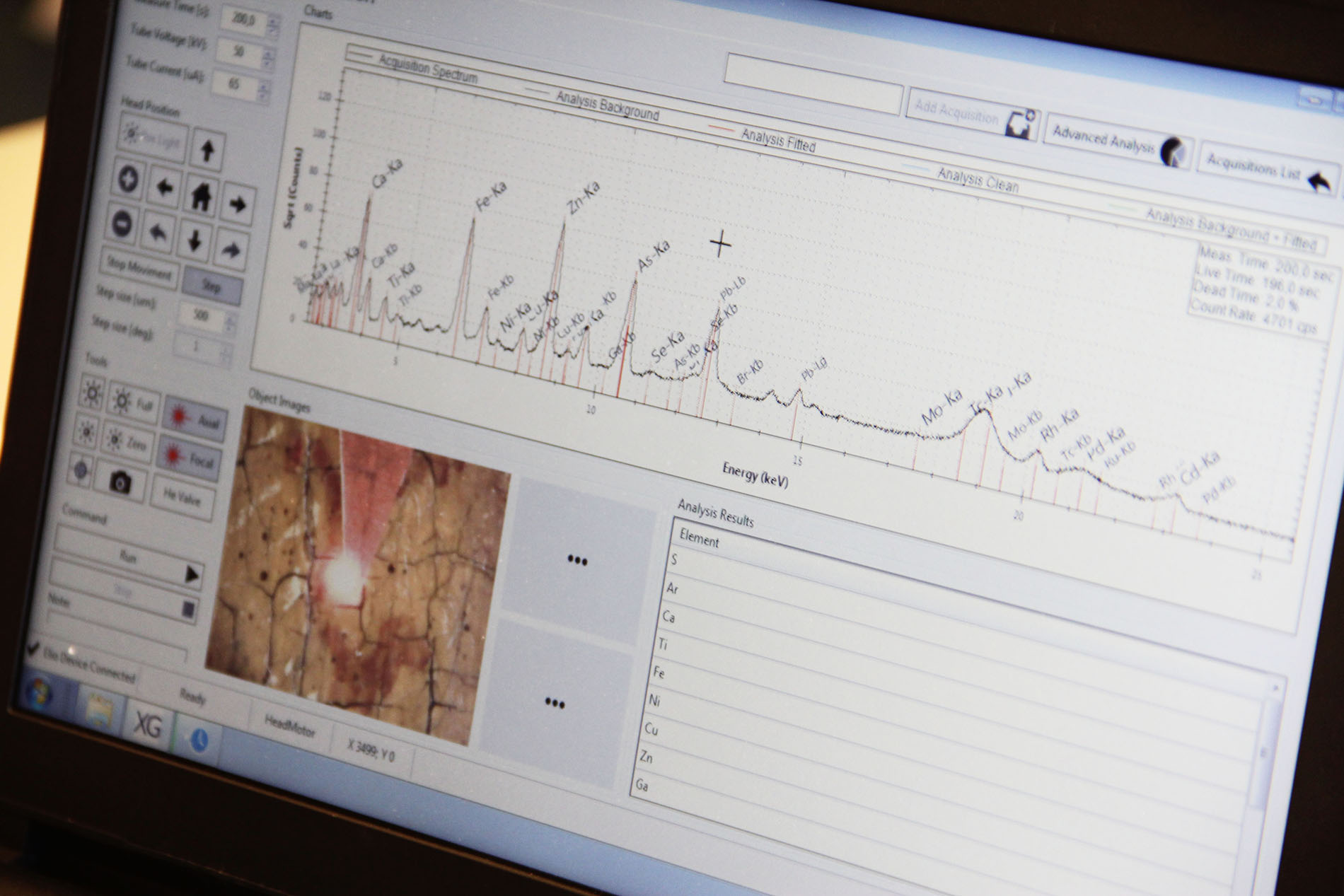

NCMA Conservator Noelle Ocon mans the computer collecting elemental data from the pXRF instrument. A blinking red light serves as a warning that the device is on — and that it’s producing harmful x-rays. People in the vicinity must remain behind the beacon until it turns off.

The pXRF software interface shows the spectrum of elements in the paint, as well as a close-up image of the focus area. The area analyzed in the above spectra appears to contain calcium, iron, arsenic, lead, and zinc — the latter suggesting a drier or pigment in the paint from the 19th century or later. Use of the pXRF was made possible by the collaboration with Uffelman, who also brought with him a portable Multispectral Imaging in the Near Infrared (MSI-NRI) instrument, which digitally captures an image of the painting, allowing the viewer to see underdrawing and compositional changes made by both the artist and later restorers.

The opportunity to see the scientific side of history and preservation has deepened Guthrie’s appreciation for the material nature of art — so much so that she’s attending the American Chemical Society’s national meeting later this year to learn about analytic chemistry in the context of cultural heritage. “A persistent and imaginative researcher, Brianna fully immersed herself in scientific conversations and studies in the lab — activities outside her normal skill set,” Nisbet says. “That will make her a much better art historian in the future.”