As a storm quickly approaches, marine scientist Nathan Hall hustles to get back to shore. While he cruises through the Neuse River Estuary, students onboard shriek and laugh as the boat crashes against the swell. New to marine fieldwork, they have yet to gain their sea legs and increasingly slide further and further to one side of the boat with each bump.

Before the trip to the coast, the students spent the semester in Chapel Hill learning about marine organisms, their distribution, and interactions with each other and the local environment during a course taught Adrian Marchetti and Joel Fodrie. “We try to hit the wide sweep of as many aspects of biological oceanography as we can,” Fodrie says. “Everything from nutrient availability to the role of climate change.”

As a final component of the class, students spent a weekend taking water samples from the estuary, attending a lecture from distinguished professor Hans Paerl, conducting experiments at the UNC Institute of Marine Sciences (IMS), and touring the Rachel Carson National Estuarine Research Reserve.

Marchetti and his students wait to collect samples at one of the estuary sites. Over a dozen undergrad and graduate students, split up between two boats, participated. For many, this is their first time conducting research in any capacity, let alone on the water. “A lot of them have listed this field trip as the highlight of their program, whether it be graduate or undergraduate,” Marchetti says.

Marchetti and his students wait to collect samples at one of the estuary sites. Over a dozen undergrad and graduate students, split up between two boats, participated. For many, this is their first time conducting research in any capacity, let alone on the water. “A lot of them have listed this field trip as the highlight of their program, whether it be graduate or undergraduate,” Marchetti says.

UNC graduate student Christopher Chambers watches as classmates add a solution to a water sample, preserving phytoplankton cells for later analysis. Like plants on land, these microscopic algae use photosynthesis and convert carbon dioxide to oxygen.

UNC graduate student Christopher Chambers watches as classmates add a solution to a water sample, preserving phytoplankton cells for later analysis. Like plants on land, these microscopic algae use photosynthesis and convert carbon dioxide to oxygen.

“We understand that they play critical roles in the carbon cycle,” Marchetti says. “Every second breath you take is thanks to phytoplankton in the ocean, so understanding what’s happening with them in relation to climate change is very important for the health of our planet.”

Nathan Hall shows students a Secchi disk, used to measure water clarity. Hall, a marine scientist, frequently conducts research on the estuary to study phytoplankton. “One of the nice things about having IMS is the ability for students to learn from the greatest experts in the field in terms of local issues and local research,” Marchetti says. “They’re doing their primary research in this area so it’s a very unique opportunity.”

Nathan Hall shows students a Secchi disk, used to measure water clarity. Hall, a marine scientist, frequently conducts research on the estuary to study phytoplankton. “One of the nice things about having IMS is the ability for students to learn from the greatest experts in the field in terms of local issues and local research,” Marchetti says. “They’re doing their primary research in this area so it’s a very unique opportunity.”

A student writes notes about a field site while classmates gather water samples. At each stop, students noted the site’s coordinates, the weather conditions, and physical data like water transparency.

A student writes notes about a field site while classmates gather water samples. At each stop, students noted the site’s coordinates, the weather conditions, and physical data like water transparency.

UNC graduate student Steph Smith laughs after fellow grad student, Chad Lloyd, accidentally sprays her with a water sample.

UNC graduate student Steph Smith laughs after fellow grad student, Chad Lloyd, accidentally sprays her with a water sample.

Students chat while waiting to begin their final sample collection. By this time, they’ve already been at work for about five hours, but their day is far from over –– after a lecture at IMS from Hans Paerl on nutrient dynamics, they’ll go straight into analyzing the water samples.

Students chat while waiting to begin their final sample collection. By this time, they’ve already been at work for about five hours, but their day is far from over –– after a lecture at IMS from Hans Paerl on nutrient dynamics, they’ll go straight into analyzing the water samples.

UNC graduate student Shuo Li and UNC junior Maggie Bernish pour a water sample into a graduated cylinder while conducting experiments in the Paerl Lab at IMS. The students, who were focused on the physical parameters of the samples, investigated how phytoplankton composition varied with water salinity.

UNC graduate student Shuo Li and UNC junior Maggie Bernish pour a water sample into a graduated cylinder while conducting experiments in the Paerl Lab at IMS. The students, who were focused on the physical parameters of the samples, investigated how phytoplankton composition varied with water salinity.

Though rooted in biology, the course expands beyond one discipline. “The biology, it happens in the context of chemistry and physics,” Fodrie says. “So biological oceanography is really a class where students perceive that interdisciplinary role. We’re always leveraging what we learn from these other aspects of oceanography.”

UNC grad student Zack Taebel conducts a filtration analysis, used to separate and quantify phytoplankton from a water sample. Taebel’s team examined how the recent increase in freshwater, following winter storms and hurricanes Florence and Michael, affected phytoplankton.

UNC grad student Zack Taebel conducts a filtration analysis, used to separate and quantify phytoplankton from a water sample. Taebel’s team examined how the recent increase in freshwater, following winter storms and hurricanes Florence and Michael, affected phytoplankton.

Steph Smith and Johnson Lin look at zooplankton under microscopes. The duo explored interactions between zooplankton and bacteria, hypothesizing that these microscopic marine animals associate with distinct bacterial communities.

Steph Smith and Johnson Lin look at zooplankton under microscopes. The duo explored interactions between zooplankton and bacteria, hypothesizing that these microscopic marine animals associate with distinct bacterial communities.

Students studying phytoplankton use settling chambers to count phytoplankton cells in a water sample.

Students studying phytoplankton use settling chambers to count phytoplankton cells in a water sample.

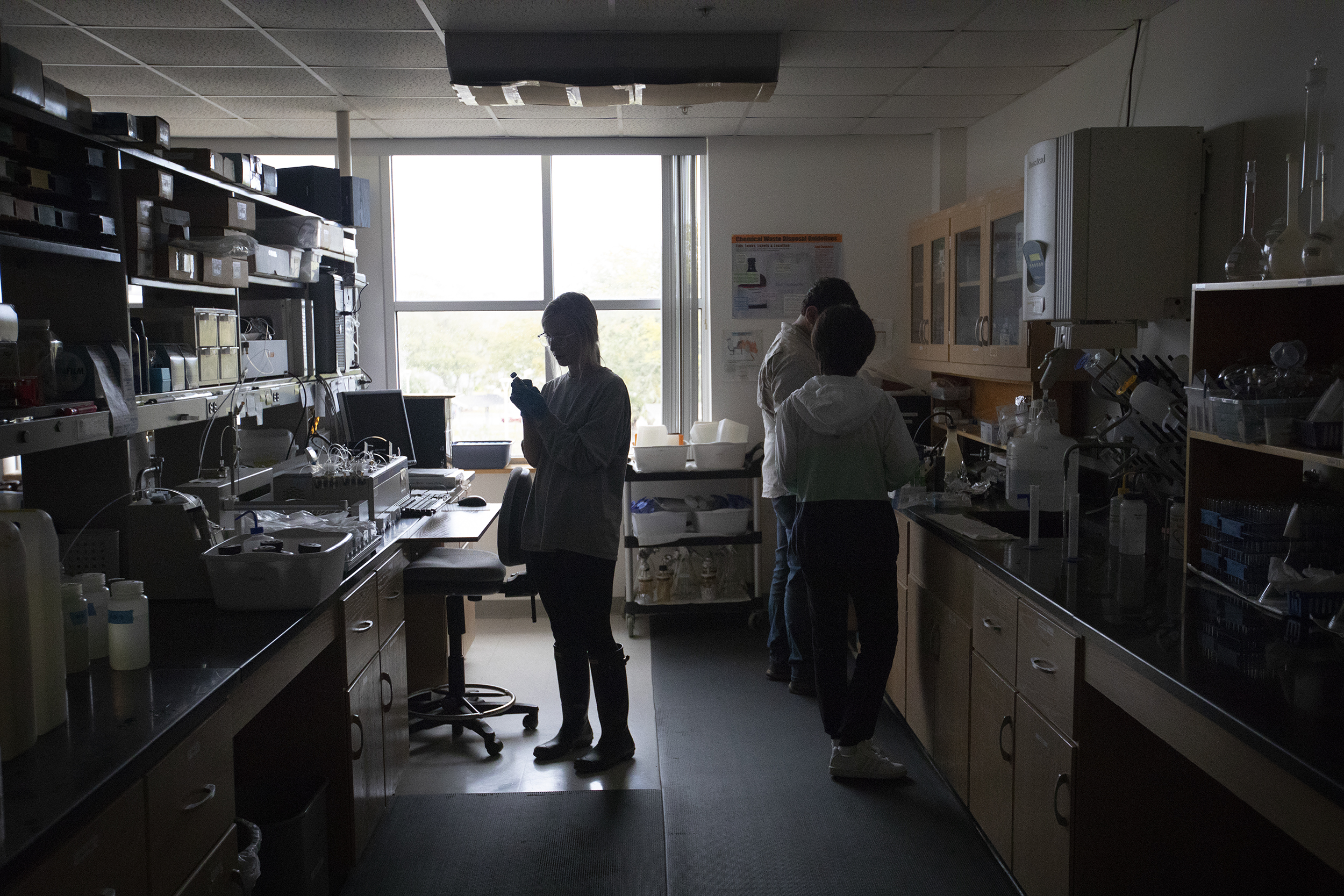

Students conduct experiments with the lab lights off to slow the process of photosynthesis. Marchetti and Fodrie believe having a facility like IMS is invaluable to their students, helping inspire the next generation of marine scientists. “I’m sort of a traditionalist when it comes to believing in the power of well-designed lectures and what that provides students,” Fodrie says. “But it’s invaluable to be able to supplement those lectures with these experiential adventures.”

Students conduct experiments with the lab lights off to slow the process of photosynthesis. Marchetti and Fodrie believe having a facility like IMS is invaluable to their students, helping inspire the next generation of marine scientists. “I’m sort of a traditionalist when it comes to believing in the power of well-designed lectures and what that provides students,” Fodrie says. “But it’s invaluable to be able to supplement those lectures with these experiential adventures.”