Even though we’re underwater, I can tell everyone is relaxed and happy. It’s a beautiful afternoon in August, and this group of UNC graduate students has spent the past week completing their scientific diver training. As we come up from our second dive of the day, we spot a giant barracuda—a familiar site around offshore dive boats in North Carolina waters. While the large fish may appear sinister, they don’t usually pose a threat to divers.

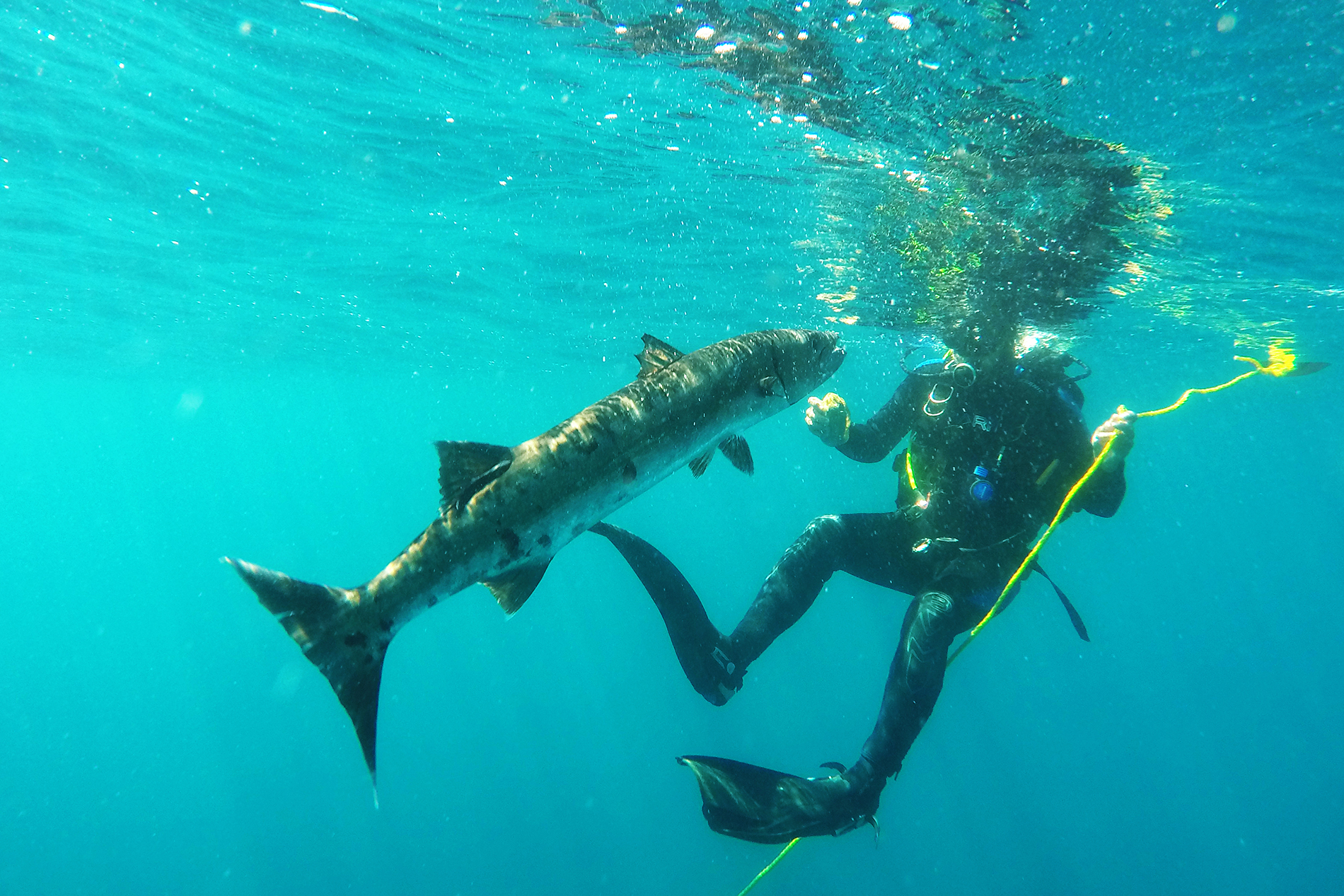

But this particular barracuda has something to prove—in a flash of bubbles, it zooms towards me, baring a set of large teeth. I kick away, just as our dive master, Glenn Safrit, swims between me and the underwater bully. It circles back around to him, biting his fin. While I take photos of this bizarre encounter, the students rush to get out of the water. The barracuda continues to act aggressively towards Safrit, but he calmly shoos it away.

Glenn Safrit sets a good example for the students in his scientific diver certification class by reacting calmly to an aggressive giant barracuda.

When I haul myself onto the deck of the R/V Capricorn, the students gush with excitement and adrenaline.

Did you see that?? That thing was enormous! It was trying to bite us!

Amidst the hullabaloo, Glenn Safrit quietly climbs back on board. He’s fine, and the barracuda has finally swam off. Safrit methodically removes his dive gear, unfazed by the dramatic end to the dive. After 40 years of working in the water, dealing with a feisty big fish is just another day at the office.

Lifelong Beach Lover

Safrit was 9 years old when his parents took him to the beach for the first time. Three days later, when it was time to pack up the car and drive back to Concord, he didn’t want to leave. “I just wanted to stay there,” he says. “The water and the waves and being in the sunshine—I loved everything about it.”

Even before that first beach trip, Safrit always loved being in water—some of his earliest memories include swimming in nearby pools and lakes. As a teenager, he completed a junior lifesaving course while at a boy’s club day camp. He completed a course in Senior Lifesaving, as well as earned Water Safety Instructor certifications and SCUBA certification while he was a student at NC State University.

In 1974, he graduated from NCSU with a degree in fisheries and wildlife biology, and took a job at the NC Division of Marine Fisheries in Morehead City. During his first year there, Safrit read the Research Diver’s Manual, he enrolled in a dive instructor course taught by the author. During that time, he received a job offer for a position in Little Washington, North Carolina, but he turned it down as the job did not involve any diving and he didn’t want to leave Morehead City.

Because the UNC Institute of Marine Sciences is located right next door to the Division of Marine Fisheries, Safrit often interacted with researchers there, including Alphonse Chestnut, director of IMS at the time.

It wasn’t long before Chestnut offered him a job.

Renaissance Man

When Safrit started working at IMS in 1977, scuba diving was still a relatively new sport. The Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI) was created just 11 years earlier in 1966, while the Diver Alert Network (DAN) followed in 1980. By the late 1980s, options for professional scuba training remained limited—especially in small-town, eastern North Carolina.

Safrit helped change that. With support from the faculty at IMS, he began the process of creating an official diving program. It took a year (and a lot of paperwork) to ensure the institute met every standard required to join the American Academy of Underwater Sciences (AAUS). In 1991, the institute was granted membership, and has remained active ever since.

“The dive safety officer position can seem thankless at times,” says Niels Lindquist, a researcher who has worked at IMS for over three decades. “Glenn had to repeatedly remind student divers (and often faculty members, too) to log their dives so he could submit the required annual dive program summary to AAUS.” Safrit always approached the tedium of paperwork with the same cool and collected manner he employed while diving.

“He is particularly good with students, many of whom are often not fully aware of the challenges and dangers of working on and around the water,” says Rick Luettich, the current director of IMS.

Leader in Safety

Safrit has made over 1,500 dives, but he has never experienced decompression sickness (often referred to as the bends.) He’s had minor cuts and scrapes from coral and equipment, and the occasional sinus squeeze—where being underwater creates pressure in the nasal cavities—he’s never ruptured an eardrum. His personal safety record, and the record for students under his watch during their scientific diver training, is commendable.

Decades have passed since Jane Tucker completed her diver training under Safrit while working at IMS, but she’ll never forget when a large stingray was swimming straight toward her. Behind the ray, Tucker could see Safrit signaling to her.

“I was a new diver, and he was concerned I might not react well to being in close proximity to such a large animal.” But Tucker didn’t panic. “It was because of Glenn’s training that I stayed still in the water and calmly watched the ray gracefully ‘fly’ past me,” she says. “It was an awe-inspiring experience and a memory that has stayed with me.”

In all of his students, Safrit instilled a sense of calm and methodical way of doing things underwater, but he also challenged them. “He knew I was going to be diving in California, and he was concerned about me diving in strong currents and cold water,” recalls Samantha Joye.

During the scientific diving skills test, Safrit asked Joye to complete a rescue swim in cold, open water. “The kicker was having to rescue a guy twice my size—it was like swimming with a big bag of rocks,” Joye says. “It was hard, but I knew what I was doing because of Glenn, and I never got in a situation where my skills were insufficient to get me through it.”

Shark whisperer

While diving offshore with a team of researchers collecting juvenile queen angelfish, Safrit looked up to see a long, skinny shark heading his way.

He recalled a passage from a book written by underwater photographer Valerie Taylor, who spent years filming sharks off the coast of South Africa. If a shark ever comes towards you, Taylor wrote, react aggressively.

Sharks are curious animals—they will often bump their nose into something to see if it reacts. If the object doesn’t react, the shark may assume it’s easy prey. Armed with a stainless steel net frame, Safrit turned to face the predator head-on. When the shark was within a foot of him, he slammed the net frame across the shark’s snout.

The shark immediately turned and swam off in the opposite direction. Safrit went straight to his buddy and made a chomping motion with his hand— the underwater sign language for shark.

Years later, while waiting at a safety stop just below the surface at the end of a dive, Safrit saw a shark acting aggressively. “It put its pectoral fins down and moved its head back and forth, almost like a dog snarling,” he says. “That’s a territorial display – the shark’s way of saying that’s his or her territory, not yours.”

Safrit didn’t have to get physical with that shark, but he has handled several sharks while working above the surface. IMS is home to oldest shark research program in the country, and regular catch and release long-line surveys have taken place for as long as Safrit has been there. He’s done most of the shark trips—the only time he misses one is when he’s teaching a dive class.

Community organizer

“Being the senior scientific dive program administrator in our area, Glenn has always been a ‘go to’ resource whenever a question arose or there was a problem to be solved at one of the other labs,” says Steve Broadhurst, the dive safety officer at Duke.

Scuba diving, by nature, is a collaborative endeavor—one should never dive alone. “Getting to know the personnel and standards of other organizations is always helpful when you need to dive with another program,” Safrit says.

To that end, in 2010, Safrit helped start the Coastal Carolina Scientific Diving Association (CCSDA). The membership of the CCSDA includes every lab’s dive program, and as Safrit says, “Everybody gets a chance to meet and interact with divers from other Universities and Government organizations. IMS divers have been involved with dive operations with many of the CCSDA members”. Divers Alert Network has always sent representative’s to the annual symposium to inform attendees of the latest information in dive research.

In 2015, Safrit played a crucial role in the planning and execution of a diver emergency training exercise — perhaps the largest collaboration of its kind in this part of eastern North Carolina. The exercise included the scientific diving community and two recreational dive shops in conjunction with the U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point Search and Recovery Helicopter Squadron PEDRO. Safrit arranged for the use of IMS’s vessel, the R/V Capricorn, to be used as the large vessel training platform for simulated rescue of an injured diver.

“They lifted us up in a helicopter basket about 100 feet above the water—it was exciting,” Safrit says.

Family Man

In his small office on the back side of IMS, Safrit shuffles paperwork and discusses his plans for retirement. He has some projects to do around the house, and two teenage boys to look after—Samuel, 17 and Jesse, 14.

“I’m looking forward to getting both of them dive certified this summer,” he says. “I’ve been saying that for three years now.”

In a drawer next to hundreds of dive logs, Safrit pulls out several old sheets of color negatives—photos taken in the mid- 1980s. He remembers each photo (and each dive) as clear as yesterday. While he conducted the majority of his work in North Carolina, Safrit also made several trips to Florida and the Caribbean, assisting graduate students from marine science and biology labs on UNC’s main campus.

Safrit recalls the details of each dive with vivid detail.

After 40 years, Safrit is ready for retirement, but thankful for all the years he spent at IMS. “It’s a great place to work. I like the people, too—there’s lots of different projects, and always something new.”

But at the end of the day, Safrit’s professionalism and dedication to excellence has boiled down to one thing — “I like the ocean,” he says. “When I get in the water, I think, I have been really blessed.”