About 45 miles north of London, in a field just outside the village of Ashwell, rain begins to fall in specks on the lush green landscape. Jessica Wolfe reaches out her hand and savors the moment. She feels as if she’s been transported back in time, to the era of William Shakespeare and Francis Bacon and Queen Elizabeth I. Soon enough, the specks turn to pelting beads as thunder sounds overhead. Welcome to summer in England.

“The power of the weather and being immersed in nature — that was probably the closest I felt to being on the trail of Chapman,” Wolfe says.

A professor of English and comparative literature at UNC, Wolfe traveled to England in 2019 to research the life of George Chapman, an English scholar known for translating “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey.” She is not only writing her first biography but the first biography on the 16th– and 17th-century scholar.

Chapman has been on Wolfe’s radar since her time as a PhD student in the late 1990s.

For as long as she can remember, Wolfe has always been drawn to vague — but influential — texts and characters.

Wolfe walked through the English countryside outside George Chapman’s childhood home of Hitchin to get a feel for the places he lived during his life. He references this hill, in particular, in his translations of Homer’s poems. (photo courtesy of Jessica Wolfe)

She wrote a chapter of her dissertation on Gabriel Harvey, an English writer known more for his friendship with Edmund Spenser, author of “The Faerie Queene,” and his quarrel with Thomas Nashe, another writer of the time, than his own accomplishments. She’s also studied the work of Thomas Browne, who wrote about science, medicine, religion, and the esoteric.

“I always felt he was quirky and misunderstood — and ignored by other scholars in favor of playwrights like Shakespeare, Marlowe, and Jonson,” she says. “But their works are more relatable to present-day. It’s a lot harder to make Chapman speak to the present occasion.”

She likes the timeframe of the Renaissance because it is “just far enough away from where we are now that it’s really alien and interesting.”

The curious child

Wolfe’s academic interests did not begin with books but with places. Places like England, Belgium, and the Netherlands — where her parents took her when she was just 7 years old. She remembers visiting the Tower of London and the feeling of wind and water on the slow ferry that took them from England to Belgium.

When she was 10, her mother introduced her to the Frick Collection in New York City, despite its strict rules about letting younger children into the museum. Wolfe acknowledged this and felt honored to be there. After walking its hallways, she became enamored with two portraits by the German Renaissance painter Hans Holbein: one of the writer Thomas Moore and another of Henry VIII’s minister, Thomas Cromwell — both of whom were executed.

“I’m sure that upped my fascination with them,” Wolfe says with a laugh.

At 14, she saw her first Roman ruins in southern France — an amphitheater in Arles, a temple in Nimes, and a triumphal arch in Orange. She visited a medieval monastery surrounded by lavender and poppies, which were in full bloom.

“It was a feast for the eyes and the nose,” she recalls. “I was utterly captivated.”

Wolfe loved that the physical remnants of ancient and medieval history were everywhere, and not just in the architecture, but also in the food and culture.

“That trip was also the first time I saw the Mediterranean, and I’ve been drawn back to it many times — to France and Italy but also to some of the islands, most recently Elba and Sardinia.”

By the time she reached her senior year of high school, she’d already developed a strong passion for the past. That year, she had a “wonderful history teacher,” who taught her that to study a culture is to study everything about it, from its political philosophy and events, to art and science, to religion.

The obscure Englishman

Chapman was a poet and a playwright believed to be born in 1559, one year after Queen Elizabeth I took the throne. He is probably most known for his translation of Homer’s epics, which inspired the work of 19th– and 20th-century writers like John Keats, Oscar Wilde, and T.S. Eliot.

While his own poems and plays are less familiar to the average reader, he shared social circles with some of the most influential figures of the time: William Shakespeare, Sir Walter Raleigh, and Christopher Marlowe. He even wrote the conclusion to Marlowe’s unfinished poem, “Hero and Leander.”

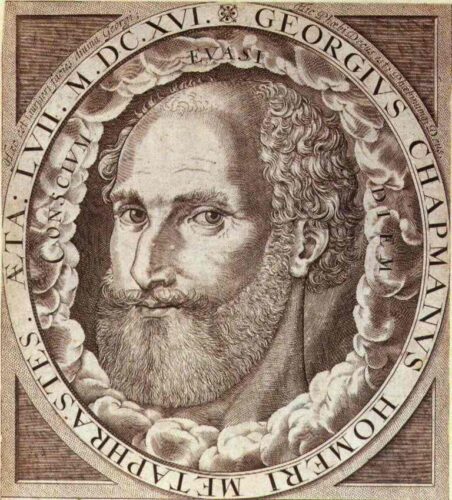

A vignette portrait of George Chapman from his book, “Whole Works of Homer.” (photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

“He was born five years before Shakespeare — and lived longer. He didn’t die until 1634. And Marlowe lived less than half that time,” Wolfe points out. “To narrate Chapman’s life and his works gives me an opportunity to produce a longer narrative about the English Renaissance and England’s relationship to the European continent at that time.”

Chapman’s verses are considered harder to understand than Shakespeare and Marlowe’s — another reason why Wolfe is drawn to him. Scholars know little about his education, only that he might have attended Oxford. He was preoccupied with French history and culture, subjects that made their way into most of his plays.

Chapman has taken Wolfe all over Europe, from his childhood home in the English countryside to the London pub where he used to meet his “less-than-savory associates.” She’s worked in more than a dozen archives in search of any documentation related to Chapman that she can get her hands on, from letters and employment paperwork to property leases and Parish records. She’s interested in visiting Aleppo to trace the English writer’s ties to the East India Company.

“Doing this research is a bit like doing a 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzle, but you only have 300 pieces and half the pieces are white,” Wolfe says, chuckling. “And you have to use your scholarly knowledge and trust your assumptions to figure out what those other pieces would be if they were there.”

Wolfe has also spent a lot of time in Paris, working within diplomatic and notarial archives to further develop her hypothesis that Chapman was employed in France by the English ambassador in the 1580s.

“That was actually where I was when the pandemic broke out in 2020, and I had to come home,” she shares. “It’s my next stop when the world reopens later this year or next.”

The original myth-buster

Since the pandemic has put the Chapman biography on hold, Wolfe has continued to work on her other project: a scholarly edition of Thomas Browne’s “Pseudodoxia Epidemica.” Wolfe calls this book a Renaissance-style “MythBusters” that exposes false beliefs about subjects ranging from magnetism to unicorns.

Browne is considered a polymath, meaning he specialized in multiple subjects, drawing on his extensive knowledge to solve problems. One of the topics he addresses in this book is the formerly commonplace belief that all land animals had a corresponding sea animal. The idea developed from animals like sea lions, catfish, and dogfish, which have been named because of their similarities to their terrestrial counterparts.

“Browne was very attuned to the problems language creates,” Wolfe says. “Language can be very useful in creating distinctions, but it can also graft on false likenesses between things.”

Another chapter delves into the concept of east and west, which Browne claims aren’t real because they are relative and not absolute terms. They are manmade concepts that have, historically, been used to maintain political and cultural distinctions or to enforce religious practices such as the direction of prayer or the placement of altars. But such debates become less urgent, or simply don’t need to take place at all, when one acknowledges that east and west are relative and not absolute.

“I think what Browne understood all too well is the belief in an absolute east and west also brings with it certain assumptions about race, certain assumptions about what it means to be western.”

Browne’s approach to the world seems more relevant than ever in today’s culture, as debates about truths and fallacies abound. In “Pseudodoxia Epidemica,” he even addresses the problematic medical practices of his time, such as the belief that drinking gold could cure your ailments.

“I think he’s concerned that false knowledge in the world of medicine can generate the kind of public health crisis that we’re currently experiencing, and of course 17th-century England had its fair share of plagues and pandemics,” Wolfe says. “But even a field as empirical as medicine can be coopted by those that don’t have their heart in the right place.”

The teacher and translator

Wolfe acknowledges that it can be difficult, at times, to understand how her studies translate to present day. Why do we study centuries-old plays, sonnets, and literary figures?

“I’m going to sound like a very old-school defender of the humanities in saying so, but the grief of King Lear, the jealousy of Othello — these are passions to which we can all at some point in our life relate,” Wolfe says. “And they’re given a grandeur on something like the Shakespearean stage that they don’t have when they are experienced by us in our own lives.”

Literature also provides space to discuss difficult topics, Wolfe says. Shakespeare’s play “Titus Andronicus,” for example, tells the story of a woman who is brutally raped and has her tongue removed and hands cut off. With the help of family members, she still manages to articulate the identities of her rapists. Wolfe was teaching this play, and others like it, during the Brett Cavanaugh hearings.

“This is a story that speaks to us, sadly, in powerful ways,” she says. “I think that, sometimes, getting students to talk about sexual violence that is mediated in time and space and culture can be a less painful way of getting those conversations going than were I to be teaching a psychology or a sociology class that has to talk about these very painful issues without a sense of distance between them.”

Renaissance writers have also written about homosexuality, race, and mental health. Wolfe’s students are often surprised to learn that the current generation is far from the first to care about these subjects. But no matter how old, Wolfe says, good writers help us understand what makes us human and what makes us tick.

“Historical texts ignite our curiosity for the unknown,” she says. “They unseat our assumptions about what is normal or natural in our own culture, and they provide life lessons and other applications that go far beyond the ability to read a literary text.”