While drafting the Bill of Rights in 1791, James Madison knew the founders needed to protect citizens from government overreach so frequently seen under British rule. Time and time again, the British government attempted to control colonial dissent by censoring critical commentary. Publishing such information was considered treason and violators were subject to swift and fierce punishment.

Freedom of the press, called “one of the great bulwarks of liberty” by the Founding Fathers, was included in the First Amendment of the Constitution in order to prevent such actions in the newly formed democracy.

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

In the case of freedom of the press, this guarantees that citizens can print and circulate news without fear of government reprisal. This right is so foundational to the United States’ Constitution, that many take it for granted. A vast number of people around the world, though, are not afforded this luxury — they receive news from state-controlled media, have restrictions on internet access, and face violence, imprisonment, or harassment for the dissemination of critical information.

Almost 230 years after the adoption of the First Amendment, it is still a point of pride for U.S. journalists — and central to the UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media.

“The faculty, students, and staff, they constitute the heart of the school,” says former dean, Richard Cole. “But the soul of the school you could encapsulate in three words: The First Amendment.”

Using this as a bedrock, the school trains the next generation of journalists and media professionals to accurately and ethically inform the public through innovative storytelling.

“There’s one recurring theme throughout the history of journalism at Carolina,” says Tom Bowers, author of “Making News: One Hundred Years of Journalism and Mass Communications at Carolina” and professor emeritus at the school. “That’s being responsive to the needs of the students, the university, the state, and society at large.”

Laying a foundation

Journalism at UNC began almost 70 years before the journalism school was even established.

In the late 1800s, students of the University Press Association sent regular news dispatches to their hometown newspapers — an act supported by the university, being its only source of publicity. Also during this time, the University Athletic Association created a weekly publication of athletic events called The Tar Heel, which has since evolved into the student newspaper, The Daily Tar Heel.

Within the industry, yellow journalism of the 1800s – newspapers using sensationalized tactics like shocking banner headlines, exaggerated facts, and even bogus stories — was common. This 19th century version of “fake news” is even credited as igniting the Spanish-American War.

The turn of the next century saw the rise of investigative reporting. Works like Ida B. Wells’ “The Red Record,” Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle,” and Ida Tarbell’s “The History of the Standard Oil Company” exposed social wrongdoing and corruption, earning them the title of “muckrakers” by Theodore Roosevelt. Literature from investigative journalists was popular among the public and influential in the creation of Progressive Era-reforms.

In 1909, largely due to a push from students, Edward Kidder Graham taught the first journalism course within the Department of English. While a handful of journalism schools began forming in the U.S., not everyone was on board.

“There was a feeling among newspaper people that an education in journalism was probably a waste of time,” Bowers says. “The prevailing attitude was, if we get college graduates we want them to be generalists — to know a little bit about a lot of things and we’ll teach them what they need to know about being a journalist.”

At the same time, there was a shift within the industry establishing professionalism and objectivity. Thus, a relationship between the university and North Carolina newspapers was formed in 1916. Twice a year, this partnership offered training to newspaper staff and acted as an informal pipeline for students pursuing a career in the field. Graham, then UNC president, likened the role of journalists to the role of the university — both obligated to serve the public interest.

In 1924 the Department of Journalism was created, with Gerald W. Johnson serving as chair and sole faculty member. Two years later Johnson was succeeded by Oscar “Skipper” Coffin, who became legendary within the program.

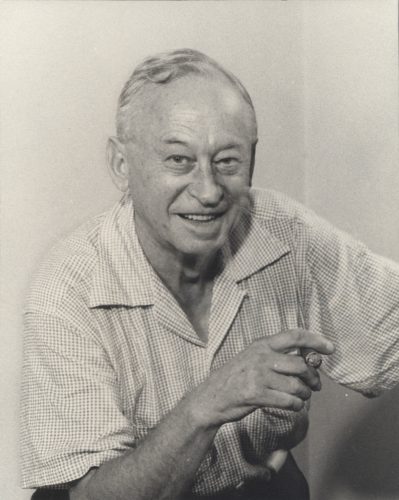

“If Oscar Coffin hadn’t existed I would have had to make him up,” Bowers says. “He gave me a lot to write about. He was quite the character.”

Once quoted as saying, “A journalist needs a graduate degree like a hog needs spats,” Coffin was a stereotypical newspaperman of the era. He started every morning with a beer at the local bar, The Shack, before heading into the office. Despite his severe asthma, Coffin was almost always seen with a cigar in hand. At the end of the day, he would return to the bar for another round of drinks and smokes.

“Students soon learned that The Shack was where Skipper had his office hours. If you wanted to talk to the head of the department that was the place to go,” Bowers says. “So, you can imagine what the straight-laced academic people thought.”

The 1930s and ’40s saw an expansion of journalistic mediums. Radio was the dominant electronic media for news and entertainment, with programs like Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Fireside Chats” and the broadcast of Orson Welles’ “War of the Worlds.” Newsreels, the predecessors of TV news, were shown movie theaters each week. In the wake of the Great Depression, a New Deal agency called the Farm Security Administration employed photojournalists like Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Gordon Parks to shed light on the challenges of poverty.

To keep pace with these developments, the university sought accreditation for the Department of Journalism. Although beloved by students, Coffin’s image and philosophy about academia weren’t helpful in this pursuit. Unsurprisingly, the department failed its first attempt in 1948. The university vowed to improve by updating facilities, expanding courses — like those in photojournalism, newspaper advertising, radio, business journalism, and journalism history — and in 1950 created the UNC School of Journalism.

Building a reputation

By 1953, Coffin resigned as dean and was replaced by Neil Luxon, marking a turning point in the school’s academic standing. Luxon wanted to create a program that could compete with prominent journalism schools around the country. He saw a strong academic foundation and graduate program as vital in this goal.

Luxon hired new faculty members with PhDs, and the graduate program was created in 1955. The school was accredited three years later. The development of a doctoral program in 1964 and continued focus on research strengthened its academic position.

“The evolution of research in the school is important. Skipper Coffin didn’t see any reason for it,” Bowers says. “Luxon recognized that journalism has to be a legitimate academic program on campus. So, you have to do what other departments are doing: Faculty members must conduct research.”

An early research focus was understanding the effects of media exposure on public attitude and behavior. In the 1980s, social science methods and computation were woven into reporting — a concept now called data journalism. The school was also a pioneer in developing the field of health communication, sparking a national movement within the industry.

That strong legacy of forward-thinking continues. Today, the school is home to thriving research programs, ranging from how media technologies affect democracy to analyzing messaging about social distancing in the age of COVID-19, and new avenues in which the media business can succeed.

Finding a home

For consumers, the 1980s meant more media options. Deregulation in television opened the market for competition, leading to more channels and the expansion of nightly cable news broadcasts. Female and minority television personalities like Oprah Winfrey, Connie Chung, and Barbara Walters were gaining popularity. The magazine industry was booming, with a focus on streamlining content for specific audiences. On top of all of this, talk of interconnected electronic networks promised to radically change the way information was disseminated.

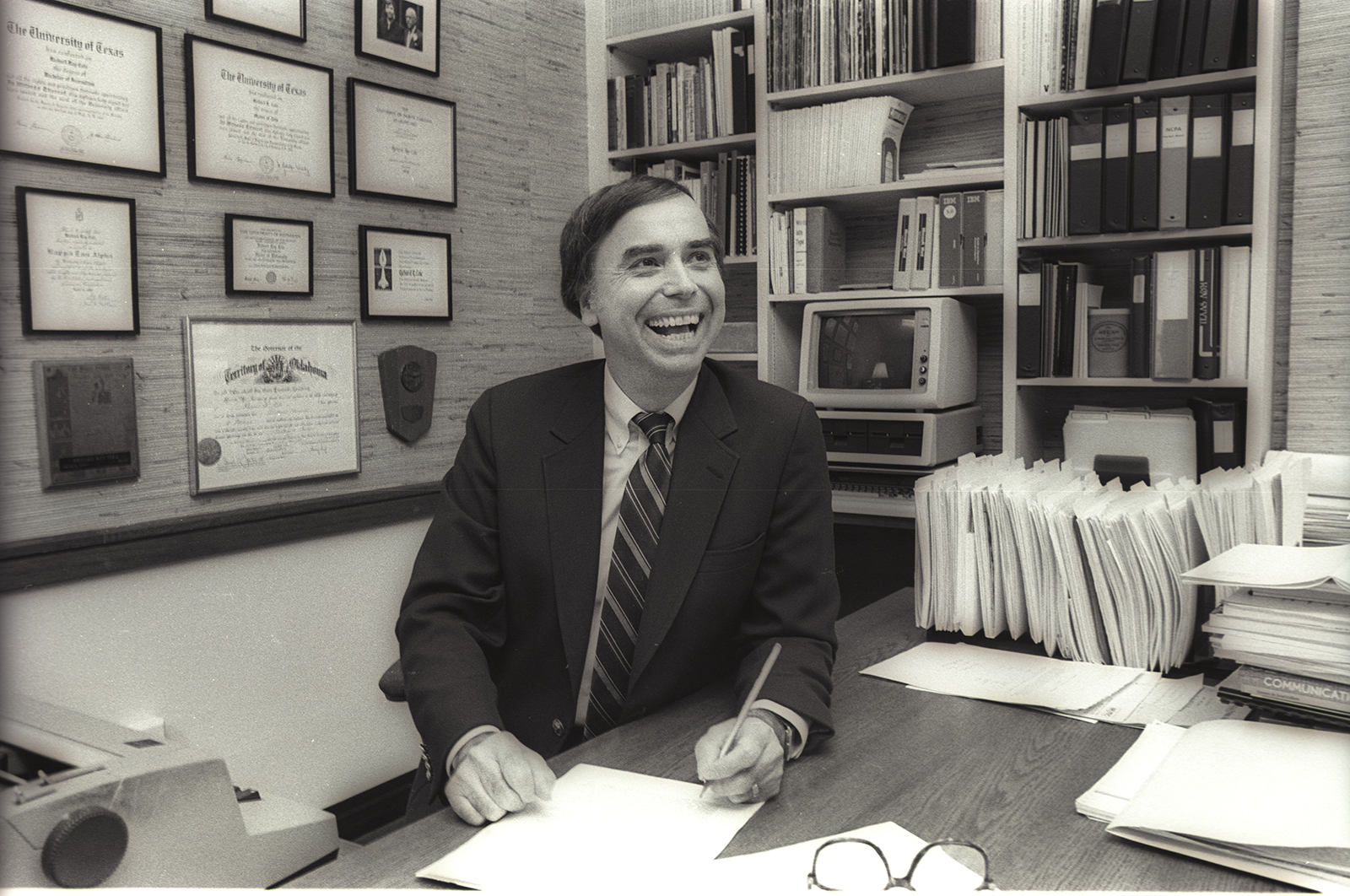

For Richard Cole, who became dean in 1979, it was important for the school to keep up with these changes. While the school’s first computers were purchased in 1968, a more advanced computer lab in 1981 — with an impressive set of 17 video display terminals and a phototypesetter — allowed students to efficiently lay out newspaper pages digitally.

“They were clunkers compared to today,” Cole laughs. “That was long before the computer became standard in people’s homes. So, as an instructional tool we realized the day of the computer was here and we had to get into it as soon as we possibly could.”

To reflect the broadened definition of media, the school’s name was changed to the School of Journalism and Mass Communication in 1990. The following year saw the addition of sequences in visual communications and public relations — the latter which now enrolls over a third of the school’s students. Like the addition of the advertising sequence, which had already been around for two decades, the step further strengthened this idea of the “new media” era.

When Cole began his deanship at just 37 years old, he didn’t expect fundraising to be such a big part of the job. Luckily for the school, he was good at it.

One of the beneficiaries of this fundraising was the graduate program. Funding for the Freedom Forum PhD Program —which began in 1995 and lasted seven years — provided financial support to news professionals pursuing a doctoral degree. Beginning in 1997, the Roy H. Park Fellowship Program provides graduate and PhD students full-ride scholarships. This set the tone for a lasting relationship with Park family, now the school’s largest private donors to date. Since its inception, the fellowship program has benefited more than 450 graduate students.

Perhaps the biggest change during Cole’s tenure was making Carroll Hall the new home for the school in 1999. Having long outgrown its location in Howell Hall, faculty and classes were dispersed over five areas of campus.

“You just can’t operate efficiently if you’re spread out,” Cole says. “You need to rub shoulders in hallways and talk and be able to confer. You just need to all be together.”

When the UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School left Carroll Hall, Cole persuaded the Provost to let the school move in and raised over $12 million to update facilities like computer labs, dark rooms, and broadcast studios.

“By the time he left the dean’s office 26 years later, he had changed the school in ways that made it almost unrecognizable compared to when he started,” Bowers writes in his book.

The evolution of the school throughout its 50-year history, including dramatic changes under Cole, paid off. In 2003, the Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communications said the school “is recognized by academics and media professionals as perhaps the best program in the nation. Many believe it has the best balance of any journalism-mass communication school because it places appropriate emphasis on both scholarly productivity and professional excellence. Moreover, it combines the best in undergraduate and graduate education.”

This reputation helped the school remain confident in what would prove to be difficult years for journalism. While the digital era began in the 1980s and picked up speed in the ’90s, the 21st century would prove to be a time of reckoning for the industry.

Reimagining journalism

At the turn of the millennia, media outlets were struggling to find their place online. Print journalism experienced an especially difficult time.

“A lot of newspaper people, they stuck their heels in the sand,” Cole says. “From a business perspective, they didn’t adapt.”

With unlimited space on websites, advertising prices plummeted — and with them, print’s main source of revenue. Those who moved content online were slow to charge for digital subscriptions. Once they did years later, readers were reluctant to pay for something previously offered for free. The industry then took a hit with the financial crisis of 2008, and many never recovered.

In the wake of the recession, news giants like Gannett, McClatchy, and BH Media began buying up local outlets, slashing budgets, and squeezing profits before shutting them down for good. In 1990, almost half a million people worked in the U.S. news business. By 2017, this number was cut by more than 50 percent to 173,900. The result has been news deserts — communities with limited access to credible and comprehensive local news and information — across the country.

So, why pursue a career in journalism? That’s something Susan King, the school’s dean since 2012, has been asked plenty of times.

“The finances are hard. But, to me, we’ve never had better journalism,” she says. “If you look at the kind of work done in visual data around COVID-19, it’s fantastic. If you go online and look at some of the videos that are integrated into the text, it’s so much more dynamic. When people say there are no jobs, I say ‘I’m sorry, my students are getting good work.’”

Cole shares this sentiment when faced with pessimism.

“Many are on hard times,” he says. “But journalism itself is not on hard times. It just has new forms.”

Part of this adaptation was in progress before King arrived at UNC. Under Dean Jean Folkerts, who served from 2005 to 2011, an emphasis was put on hiring digitally-focused faculty. A two-year online graduate degree in technology and communication gives working professionals insight into new communication strategies. In addition, UNC Reese Innovation Lab provides a space for digital entrepreneurship, design, and experimentation. The lab incorporates new technologies —like artificial intelligence, augmented reality, and virtual reality —into journalistic storytelling.

Steven King teaches his virtual reality class in a specially designed fully furnished virtual classroom during COVID-19 shelter-in-place orders (photo courtesy of Steven King).

“I came in at this moment of complete and utter redefinition of what news is in America,” King says. “Lots of things were already happening here, and my job was just to help continue that change.”

That change included redefining the roles of journalists. Previously, journalists were siloed into separate responsibilities: reporters, news anchors, photographers, designers, and producers were specialists within their specific area. Those lines have blurred. A reporter on assignment may also shoot and edit video and take photos for a multimedia package. Students are now equipped with skills crossing a variety of disciplines in order to prepare them for this multitasking mentality.

With stories being told on multiple platforms, collaboration has also become increasingly important and is reflected in the school’s collaborative capstone courses. These courses, like one called Media Hub, allow students to spend a semester focusing on long-form storytelling. By teaming up with peers from other disciplines within the school, they learn multifaceted approaches to journalism. These high-level courses have helped shine a spotlight on UNC undergraduate exceptionalism, winning them accolades like five out of the last six Hearst Journalism Award national championships — often called the Pulitzer Prize of college journalism.

Because the business model of news has changed dramatically in the past 20 years, so has entry into the field. Not only are UNC students prepared for traditional news positions — like working as a staff member for a publication or broadcast network — but they are also prepared to define their own career with positions like freelance or digital startups. Emphasis on teaching the business side of the industry — including guidelines for freelancing fees and copyright law — has been important in this preparation.

Changing curriculum and expectations isn’t cheap. Fortunately, the school received tremendous financial support to accelerate these transitions: a $10 million donation from the Curtis family in 2018 and $25 million from Walter Hussman for the now named UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media. King explains these gifts will be used to retain the highest faculty, staff, and resources for students, as well as support the new Curtis Media Center, slated to open in the fall of 2021.

The school’s next strategic plan for development focuses on “igniting the public conversation,” King says. “Whether you’re a journalist or you’re in PR and advertising, what are the issues that really bind a community, the nation, or the world?” she asks.

One of these issues is the need for greater diversity within the field. Addressing this issue, UNC has partnered with the Ida B. Wells Society for Investigative Reporting — an organization dedicated to training investigative journalists and increasing diversity within the field. The society is led by Nikole Hannah-Jones, a Carolina graduate and Pulitzer Prize winning journalist from The New York Times Magazine; Ron Nixon, the international investigations editor at The Associated Press; and Topher Sanders; who covers race, inequality, and the justice system for ProPublica.

Nikole Hannah-Jones, Ron Nixon, and Topher Sanders are founders of the Ida B. Wells Society for Investigative Reporting, an organization dedicated to training investigative journalists and increasing diversity within the field (photo courtesy of UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media).

Additionally, the school is building upon other programs and partnerships to amplify diverse perspectives. The Chuck Stone Program for Diversity and Education in Media trains and mentors top high school students with diverse experiences from across the nation, and partnerships with Capitol Broadcasting and Bloomberg News are designed to increase diversity within the industry.

Another conversation being had is how to reshape the industry’s business model to include sustainable profits. The UNC Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media is leading this discussion. Not only is the center highlighting challenges faced by news organizations today, but also creating solutions. One such program is Project Oasis, a partnership with Google News Initiative to develop best practices for local news startups.

While the UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media has undergone many changes — with many more to come — King says some things will always remain.

“We need to deeply root students in the values that have been clear since the 1950s: serving the public, building on facts,” she says. “The modes of operating have completely changed, but the skills and values of journalism haven’t. The tradition [at Carolina] of doing really deep storytelling — factually-based, innovatively told, and engaging an audience on multiple fronts — that continues.”