Q: When you were a child, what was your response to this question: “What do you want to be when you grow up?”

A: I always liked building things, but I also enjoyed the intellectual challenge I experienced at school. Growing up in South Dakota, I didn’t find many mentors with careers that combined those two things. One thing is for sure: I never dreamed I would be a scientist. You could have told me I would play professional water polo and that would have seemed more realistic — and I’m not even a good swimmer.

Q: Share the pivotal moment in your life that helped you choose your field of study.

A: The summer after my second year at the University of South Dakota, I was selected to participate in a program funded by the National Science Foundation at Columbia University. Moving from a town of 10,000 people into the middle of Manhattan was overwhelming, but I quickly found my calling in the competitive, engaging, and fast-paced atmosphere of a high-level research lab. I had never been around a group of such intellectually stimulating and dedicated people, and the hands-on aspect of building organic molecules fulfilled my passion for making things. I ended that summer fully committed to a career in science and have not looked back since.

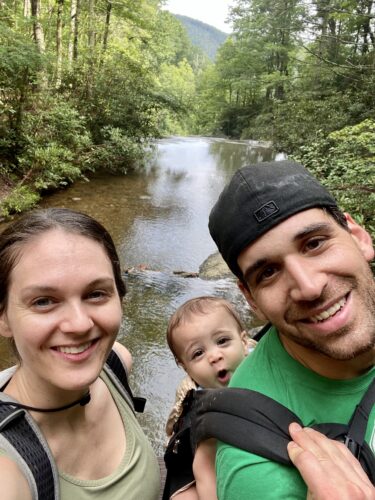

Leibfarth with his wife Janelle Bludorn, a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Allied Health Sciences, and their son Lawrence at South Mountain State Park in North Carolina.

Q: Tell us about a time you encountered a tricky problem. How did you handle it and what did you learn from it?

A: During my preparation for a fellowship interview, I had to convey the importance of my research program to an interdisciplinary panel in 10 minutes. I gathered a group of faculty with a diverse array of experience to listen to my first practice talk. It went horribly. Many people I had great respect for watched me fail. The suggestions that I got out of that day, though, completely changed my approach to the lecture. A week later, I stood in front of the panel with confidence knowing that I had tested multiple hypotheses on how to give this lecture and had prepared well.

I received the fellowship, but more importantly I grew as a communicator and relearned important lessons. The faster you fail, the faster you will achieve your goals. Trust yourself. While everyone’s advice is important and appreciated, there comes a time when you have to take ownership of the products of your intellectual work. Trust your preparation and your instincts; the world needs more unique and singular voices.

Q: Describe your research in 5 words.

A: Plastics for a sustainable future.

Q: What are your passions outside of research?

A: I love team sports. Research and work are part of my life – an enormously fulfilling part – but I’ve learned not to confuse them for who I am. We are all capable of finding fulfillment in multiple areas of life, which individually contribute to who we are and what we give back to the world. In team sports, there is no greater rush than collectively competing against an opponent and working together to achieve a level of play greater than any one individual player. I tend to play and watch basketball and soccer as much as time allows. I still try and get out on the court or field regularly. I also still try and get better – while I am not as fast as I once was, getting older doesn’t mean you can’t improve your footwork, shot, or positioning.